Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Christian AnarchismChristian anarchism is an ideology which combines anarchism and Christianity. The foundation of Christian anarchism is a rejection of violence with Leo Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God Is Within You regarded as a key text.[1] Tolstoy sought to separate Russian Orthodox Christianity, which was merged with the state, from what he believed was the true message of Jesus as contained in the four Gospels and specifically the Sermon on the Mount. Tolstoy takes the viewpoint that all governments who wage war, and churches who in turn support those governments, are an affront to the Christian principles of nonviolence and nonresistance. Although Tolstoy never actually used the term "Christian anarchism" in The Kingdom of God Is Within You, reviews of this book following its publication in 1894 coined the term.[2] Christian anarchism appears closer to communist anarchism than to individualist anarchism,[3] except for some strains of Christian anarchism that appeared in America which are more individualistic.[4]

[edit] History[edit] The Life and Teaching of JesusSee also: Ministry of Jesus

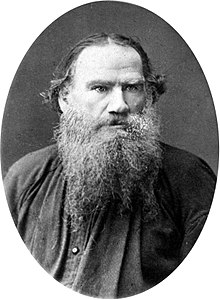

Leo Tolstoy wrote extensively on Christian anarchism.

More than any other text, the four Gospels are used as the basis for Christian anarchism, according to Dorothy Day, Ammon Hennacy and Leo Tolstoy, who constantly refer back to the words of Jesus in their social and political texts. For example, the title "The Kingdom of God is Within You" is a direct quote of Jesus from Luke 17:21. Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement particularly favored the Works of Mercy (Matthew 25:31–46), which were a recurring theme in both their writing and art. Many Christian anarchists say that Jesus opposed the use of government power, even for supposedly good purposes like welfare. They point to Luke 22:25, which says: "The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over the people; and those who exercise authority over them call themselves –Benefactors.– But you are not to be like that." Jesus antagonised the –system– ruled by Satan: "He sent me forth to preach a release to the captives, to send the crushed ones away with a release." (Luke 4:18,19, John 12:31, 14:30, 16:11, 17:16, 18:36). He was against human leadership (Matthew 23:8-12), and he refused to be made king (Matthew 4:8-10 John 6:15). The first Christians opposed the primacy of the State: –We must obey God as ruler rather than men– (Acts 4:19, 5:29, 1 Corinthians 6:1-6); "Stripping the governments and the authorities bare, he exhibited them in open public as conquered, leading them in a triumphal procession by means of it.– (Colossians 2:15). Eschatology identifies the State with the wild beast (Revelation chapters 13, 14, 17) and predicts an end to oppression: "The meek ones will possess the earth." (Psalms 37:10,11,28). The anarchist attitude comes from the Old Testament: Nimrod was disapproved for becoming a dominator (Genesis 10:8,9). Abraham, who left civilization to life in tents, conflicted with Nimrod. (Jewish tradition Gen. R. Pesik. R.). Moses led the Hebrews out of captivity to the Egyptian state (Exodus 3:7,10), and the nation remained three centuries without king: –In those days there was no king in Israel. As for everybody, what was right in his own eyes he was accustomed to do." (Judges 17:6, 21:25). Gideon refused to be made king: "Jehovah is the one who will rule over you." (Judges 8:23), and his son described the state as parasites (Judges 9:8-21). Samuel then warned the Hebrews against the evils of a kingdom (1 Samuel 8:5-18). The prophets disapproved domination (Ecclesiastes 8:9, Jeremiah 25:34, Ezekiel 34:10, 45:8, Hosea 13:10,11), and a God's kingdom of freedom was envisioned (Isaiah 2:4, 65:22). [edit] The early ChurchSee also: Early Christianity

Some of the early Christian communities seem to have practiced certain features of anarchism. For example, the Jerusalem group, as described in Acts, shared their money and labor equally and fairly among the members.[5] From the earliest period, women and men seem to have shared religious duties equally, though the public offices, such as missionary work and Temple observances, seem to have been held mostly by men.[6] However, note the case of Phoebe in Romans 16:1-2: "I commend to you Phoebe our sister, who is a servant (îîîîî¿îî¿) of the church in Cenchreae, that you may receive her in the Lord in a manner worthy of the saints, and assist her in whatever business she has need of you; for indeed she has been a helper of many and of myself also."Referring here to Phoebe, the word rendered "servant" being in the Greek îîîîî¿îî¿ (di'a–ko–nos), the parallel English word being deaconess, and in the context of the above quote, this denotes a servant who is given servants to manage, in effect, a deaconess,one who delegates, a manager, though in most ways, Christianity did not differ from any of the other Jewish sects active in the ancient world. Some, such as Ammon Hennacy,[7] have claimed that a "shift" away from Jesus' practices and teachings of nonviolence, simple living and freedom occurred in the theology of Paul of Tarsus, see also Paul of Tarsus and Judaism. These individuals suggest that Christians should look at returning to pre-"Pauline Christianity". Although there is some evidence that egalitarian Jewish Christians existed shortly after Jesus's death, possibly including the Ebionites, the majority of Christians soon followed a more hierarchical religious structure, particularly after the First Council of Nicaea (see also First seven Ecumenical Councils). Other Christians say that Paul's teachings emphasized congregational autonomy, servant-like leadership within the churches, prohibitions on one-man rule even in a local church, and other practices which contrast with this claim.[citation needed] Evidence of this interpretation can be found in Galatians 3:28. [edit] The conversion of the Roman EmpireSee also: Constantine I and Christianity

After the conversion of the emperor Emperor Constantine, Christianity was legalised under the Edict of Milan in 313 bringing an end to the persecution of Christians. Some Christian anarchists argue that this merger of Church and state marks the beginning of the "Constantinian shift", in which Christianity gradually came to be identified with the will of the ruling elite and, in some cases, a religious justification for the exercise of power.[citation needed] [edit] Anarchist Biblical views and practices[edit] AntinomianismMain article: Antinomianism

Some Christian anarchists self-identify as antinomian, often meaning that they do not consider themselves subject to a moral law given by religious or other authorities, but most frequently applying to the Old Testament. Anne Hutchinson was among the early Christian anarchists in America in the 1600s, holding to a belief in the form of, or similar to, individualist anarchism, upholding the right of individuals to determine their own lives.[8][9] Many base their beliefs upon an interpretation of the simple principles and historic messages of Jesus, such as the Sermon on the Mount, while others hold a higher critical view of the Bible, allowing for more lenient interpretation. Opponents of Christian anarchism, ranging from Jewish to Catholic to certain Protestant sects, have criticized the anarchist viewpoint for what they view as rejection of the "inerrant Word of God" and also of church leadership. They believe that there is a need for a law to maintain order, while anarchists claim that people do not require legislation. See also Biblical law in Christianity. [edit] MysticismSee also: Christian mysticism and Christian meditation

The spirituality of a Christian anarchist can be as diverse as in any Christian tradition. For Christian anarchists who have their roots in the New Testament their spirituality may be described as mystical but is also very orthodox.[citation needed] In both Christian monasticism and lay spirituality certain elements of anarchism which, while being present in normative Christianity, move more to the forefront. Thomas Merton, for instance, in his introduction to a translation of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers describes these early monastics as "Truly in certain sense 'anarchists,' and it will do no harm to think of them as such."[10] It is also written that "As of the 4th century A.D., the desert lands of Egypt saw the beginning of the longest-living anarchic society of all time: that of the Christian anachorites." [11][12] Directly, anarchists have borrowed from Quakerism the method of facilitation and meetings known as consensus decision making. This technique, which forms a fundamental part of Quaker worship, is used in most anarchist meetings.[13] [edit] Pacifism and nonviolenceMain articles: Christian pacifism and Anarcho-pacifism

Many Christian anarchists, such as Leo Tolstoy and Ammon Hennacy, are pacifists opposing the use of both proactive (offensive) and reactive (defensive) physical force. Hennacy believed that adherence to Christianity meant being a pacifist and, due to governments constantly threatening or using force to resolve conflicts, this meant being an anarchist. These individuals believe freedom will only be guided by the grace of God if they show compassion to others and turn the other cheek when confronted with violence. The links between other philosophies of Christian anarchists are also deeply tied to pacifism, more so than their equivalents in secular anarchism and state-sponsored churches. A few of the key historic messages many Christian anarchists practice are the principles of nonviolence, nonresistance and turning the other cheek, which are illustrated in many passages of the New Testament and Hebrew Bible (e.g. the sixth commandment, Exodus 20:13 and Deuteronomy 5:17, "You shall not murder"). [edit] Simple livingMain article: Simple living

Christian anarchists, such as Ammon Hennacy, often follow a simple lifestyle, for a variety of reasons, which may include environmental awareness or reducing taxable income. [edit] States and state control

The most common challenge for the Biblical literalists is integrating the passage in Romans 13:1–7 where Paul defends obedience to "governing authorities", arguing that "there is no authority except that which God has established. The authorities that exist have been established by God." Christian anarchists who subscribe to Paul's teachings argue that this chapter is particularly worded to make it clear that organizations like the Roman Empire cannot qualify as governing authorities because they are not "approved" of God and do not recognize Him in word or action.[citation needed] If it could, then, according to Paul, "they [Christians] would have praise from the authorities" for doing good. Instead the early Christians were persecuted by the Roman Empire for doing good, and became martyrs. Further, the "governing authorities" that are legitimate in the passage were never given the authority to make laws, merely to enforce the natural laws against "doing harm to a neighbor" in verses 8-10 (see tort and contract law).[citation needed] This interpretation makes all statute laws of states illegitimate, except as they restate Biblical moral precepts. Some Christians subscribe to the belief that God did not establish all authorities on the earth.[citation needed] A different interpretation of Romans 13 which is used to support Christian anarchism grants that the passage commands submission to all governing authorities, but points out that this does not equate to a vindication of those authorities. Vernard Eller articulates this position by restating the passage this way: "Be clear, any of those human [authorities] are where they are only because God is allowing them to be there. They exist only at his sufferance. And if God is willing to put up with ... the Roman Empire, you ought to be willing to put up with it, too. There is no indication God has called you to clear it out of the way or get it converted for him. You can't fight an Empire without becoming like the Roman Empire; so you had better leave such matters in God's hands where they belong."[14] This was the position held by French philosopher and Christian anarchist Jacques Ellul. Ernst Kaseman, in his Commentary on Romans, has challenged the usual interpretations of Romans 13 in light of German Lutheran Churches using this passage as justification to support the Nazi holocaust.[15] Others hold that Romans 13 teaches submission to the state while not encouraging or even condoning Christian participation in the workings of the state. According to this view Jesus submitted to the state while still refusing its means.[citation needed] Another passage of the New Testament also appears to require some amount of harmonization with the ideals espoused by Christian anarchism. Hebrews 13:17 commands Christians to "obey your leaders and submit to their authority",[16] without referencing to any circumstantial qualifications as to when this command applies. There are other Christians, such as Ammon Hennacy, who do not see the need to integrate Paul's teachings in Romans 13:1–7 into their anarchist way of life. Ammon Hennacy believed "Paul spoiled the message of Christ".[17] [edit] Tax resistanceMain article: Tax resistance

Some Christian anarchists resist taxes in the belief that their government is engaged in immoral, unethical or destructive activities such as war, and paying taxes inevitably funds these activities, whilst others submit to taxation. Adin Ballou wrote that if the act of resisting taxes requires physical force to withhold what a government tries to take, then it is important to submit to taxation. Ammon Hennacy, who, like Ballou also believed in nonresistance, managed to resist taxes without using force.[18] Opponents cite that Jesus told his followers to "give to Caesar what is Caesar's," (Matthew 22:21). Christian anarchists interpret this passage as further advice to free oneself from material attachment. Jacques Ellul believes the passage shows that Caesar may have rights over the fiat money he produces, but not things that are made by God, as he explains:[19]

[edit] VegetarianismSee also: Christian vegetarianism and Anarchism and animal rights

Vegetarianism in the Christian tradition has a long history commencing in the first centuries of Church with the Desert Fathers and Desert Mothers who abandoned the "world of men" for intimacy with the God of Jesus Christ. Vegetarianism amongst hermits and Christian monastics in the Eastern Christian and Roman Catholic traditions remains common to this day as a means of simplifying one's life, and as a practice of asceticism. Many Christian anarchists, such as Tolstoy and Hennacy, extend their belief in nonviolence and compassion to all living beings through vegetarianism or veganism.[20] [edit] Later anarchistic Christian groups[edit] The DoukhoborsThe origin of the Doukhobors dates back to 16th and 17th century Russia. The Doukhobors ("Spirit Wrestlers") are a radical Christian sect that maintains a belief in pacifism and a communal lifestyle, while rejecting secular government. In 1899, the Doukhobors fled repression in Tsarist Russia and migrated to Canada, mostly in the provinces of Saskatchewan and British Columbia. The trip was paid for by the Quakers and Russian novelist Leo Tolstoy. Canada was suggested to Leo Tolstoy as a safe-haven for the Doukhobors by anarchist Peter Kropotkin who, while on a speaking tour across the country, observed the religious tolerance experienced by the Mennonites. [edit] Catholic Worker MovementEstablished by Peter Maurin and Dorothy Day in the early 1930s, The Catholic Worker Movement is a Christian movement dedicated to nonviolence and simple living. Over 130 Catholic Worker communities exist in the United States where "houses of hospitality" care for the homeless. The Joe Hill House of hospitality (which closed in 1968) in Salt Lake City, Utah featured an enormous twelve feet by fifteen foot mural of Jesus Christ and Joe Hill. The Catholic Worker Movement has consistently protested against war and violence for over seven decades. Many of the leading figures in the movement have been both anarchists and pacifists. Catholic Worker Ammon Hennacy defined Christian anarchism as:

Maurin and Day were both baptized and confirmed in the Catholic Church and believed in the institution, thus showing it is possible to be a Christian anarchist and still choose to remain within a church. After her death, Day was proposed for sainthood by the Claretian Missionaries in 1983. Pope John Paul II granted the Archdiocese of New York permission to open Day's cause for sainthood in March 2000, calling her a Servant of God. [edit] Student Christian MovementStreams within the World Student Christian Federation, an international ecumenical network, follow anarchistic principles of Biblical interpretation, including non-creedal faith expressions, radical social justice activism, non-hierarchical decision-making structures and commitment to resisting oppression and imperialism. Some member movements, or Student Christian Movements, openly embrace a Christian anarchist ethic and structure, for instance the Student Christian Movement of Canada which makes decisions by consensus, adheres to a decentralized, autonomous structure and opposes hierarchies. [edit] Anarchist quotations

[edit] Bible passages cited by Christian anarchists

[edit] List of key individualsThe following people may be considered key figures in the development of Christian anarchism. This does not mean that they were all Christian anarchists themselves.

[edit] CriticismWhether or not anarchism is compatible with the New Testament is a point of contention. Some hold that one cannot consistently be a Christian and anarchist simultaneously: these critics include Christians, anarchists, and those who reject both categories. Others criticize anarchism and Christianity by agreeing that they are one and the same thing. In his last book of philosophy, Der Antichrist, Friedrich Nietzsche discussed his opinion of the relationship between Christianity and anarchism.

[edit] See also

[edit] References

[edit] Further reading

[edit] External links

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Anarchism –

Anarchism Critiques –

Anti-Marxism –

Class Analysis –

Class Conflict/Class Struggle –

Emancipation –

First International –

Freedom –

Left, The –

Left History –

Libertarian Politics –

Libertarian Socialism –

Libertarianism –

Mark, Karl –

Marxism –

Marxism Overviews –

Radical Political Theory –

Revolution –

Revolutionary Politics –

Social Change –

Socialism –

State, The –

Strategies for Social Change

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL). |

Connect with Connexions

|

|||||||