|

|

|

Toronto’s Historic Cemeteries

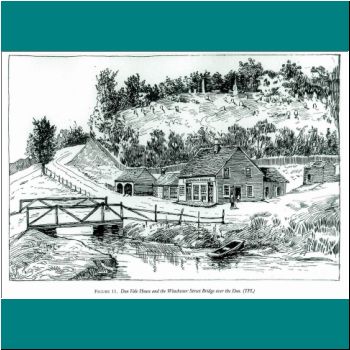

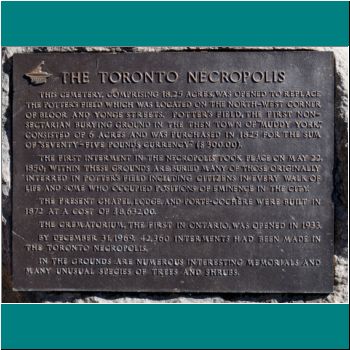

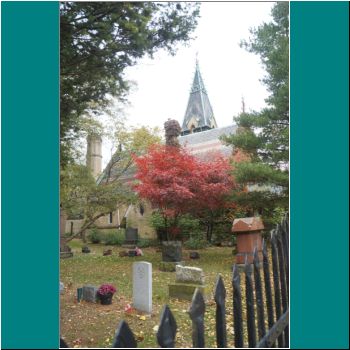

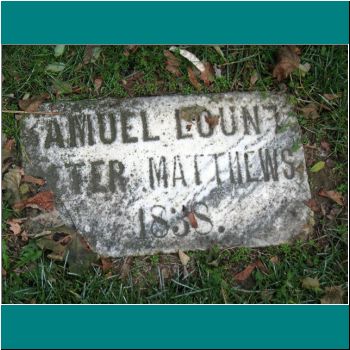

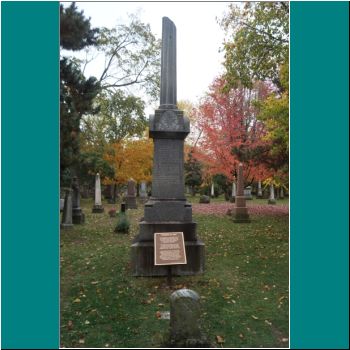

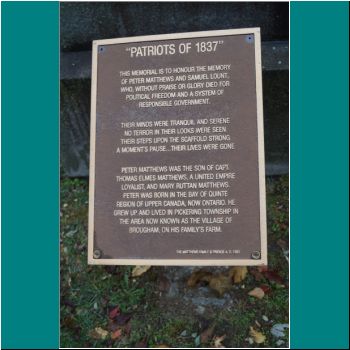

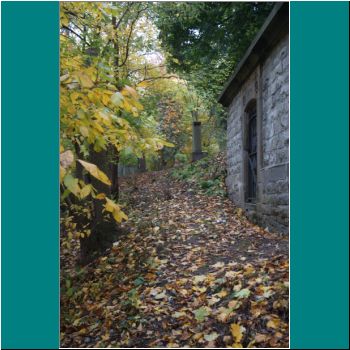

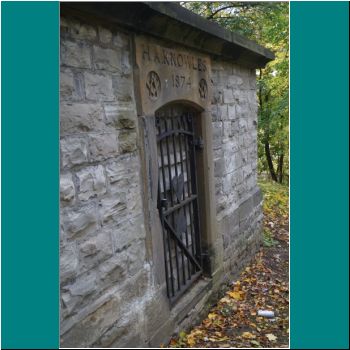

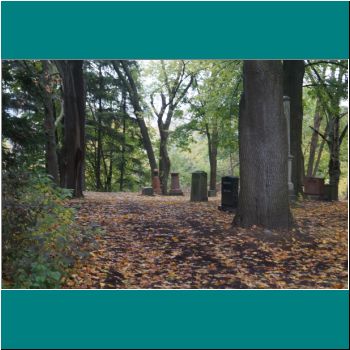

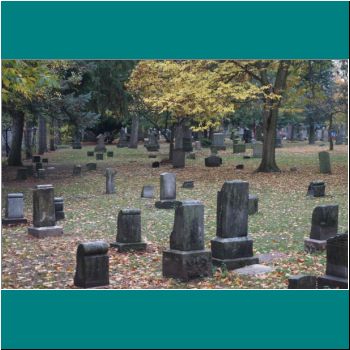

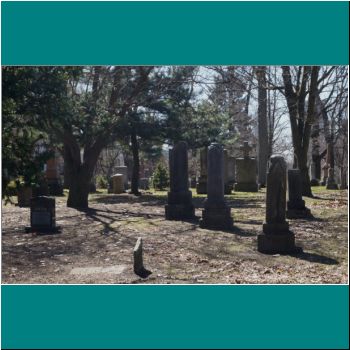

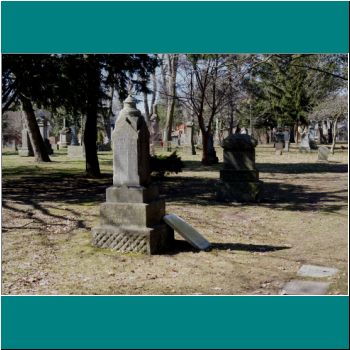

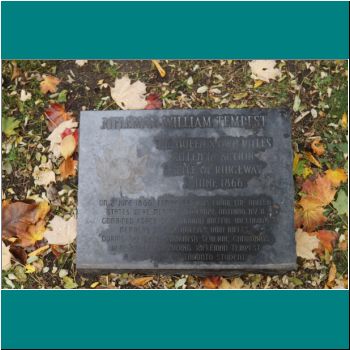

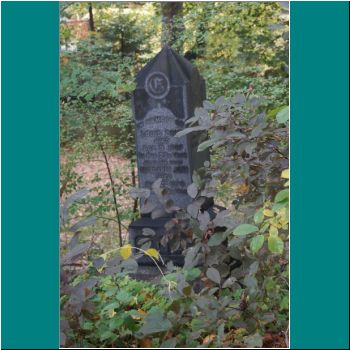

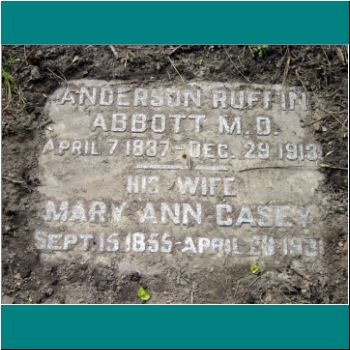

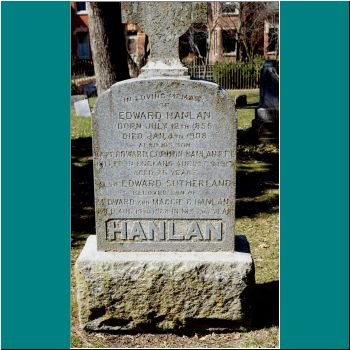

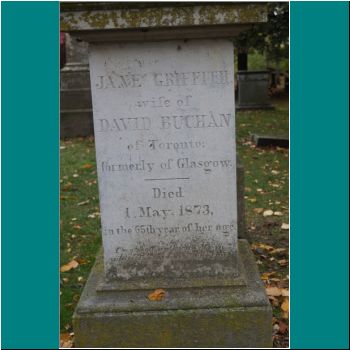

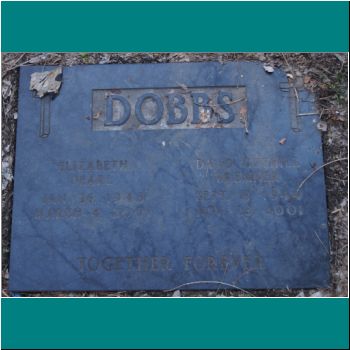

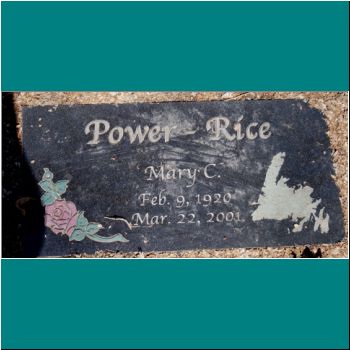

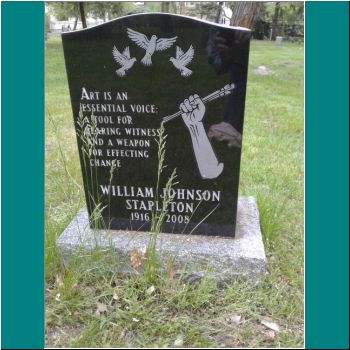

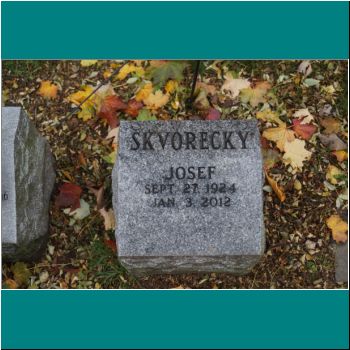

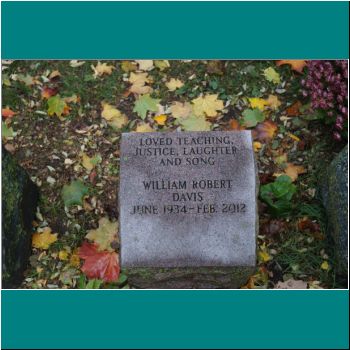

Indigenous burial grounds Indigenous peoples have lived in what is now known as Southern Ontario for thousands of years, in communities with near-by burial sites. The locations of many of these sites, especially the older ones, are not known; however at least twenty sites are believed to be within the borders of the present-day Greater Toronto area. Even where the sites are known, the locations are often not publicly disclosed, because indigenous burial sites have frequently been subject to looting and vandalism. One known location was the Sandhill site near what is now Yonge and Bloor. The site was apparently destroyed during construction work in the area in the 19th century. Another is the Taber Hill site, a Wyandot (Huron) burial mound in Scarborough, which is believed to contain the skeletons of more than 500 people. Early colonial period British colonial occupation of what is now Toronto began in 1793. The settlement, first called York, amounted to little more than a small village with adjacent farmland, between present-day George and Berkeley Streets, south of what is now Adelaide, plus a military garrison stationed farther to the west, near what is now Bathurst Street. The land to the east, up to the Don River, was set aside for government purposes rather than settlement. In the earliest days, it was common for burials to take place on the farm or property of the person who died. However, as York grew, and as more people lived in small houses with no land, this option became impractical, and small cemeteries were set up by the major religious denominations: Anglican, Roman Catholic, Methodist, or Presbyterian, usually adjacent to the church established by each denomination. As York grew and its population became more diverse, it became clear the town needed a burial ground that was not controlled by a particular church. The church cemeteries would only accept members of their own religion for burial, and even members of their faith were rejected if they were considered to have lived in sin, had a mental illness, or had committed suicide. William Lyon Mackenzie, publisher of the Colonial Advocate, a newspaper fiercely critical of the colonial establishment, took up the issue. In an editorial in his newspaper in December 1825, he said that “to perpetuate sectarianism even beyond the grave” was “preposterous” and urged the authorities to set aside land for a publicly operated non-denominational burial ground. Potter’s Field In 1826, six acres of land were purchased for this purpose on the northwest corner of Yonge Street and the first concession, now known as Bloor Street. Initially known as the York General or Strangers Burial Ground, it came to be known as Potter’s Field. This name was a biblical reference to an account in Matthew 27:7, which relates that the money Judas received for betraying Jesus was used to buy a “potter’s” field, to bury strangers in.” In the first few years of its existence, few people were buried in Potter’s Field. This changed with the cholera outbreak of 1832, when many people died. In all, 6,685 burials took place there from 1826 to 1855, when the cemetery was closed. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Toronto’s cemeteries were seeking new locations as their original sites became full. Toronto first Catholic cemetery, opened in 1822 adjacent to St. Paul’s Basilica on Power Street, was closed in 1857, and replaced by St. Michael’s Cemetery. St. James Cemetery In 1844, the Anglican Church opened St. James Cemetery on Parliament Street just north of Wellesley, on land that was then well outside the city limits. Most of Toronto’s population lived south of Queen Street at that time. It replaced the cemetery adjacent to St. James Church on King Street. It is now the oldest continuously operating cemetery in the city. To date, over 89,000 interments and 75,000 cremations have taken place there. Because many of Toronto’s founding elite were Anglicans, St. James is the resting place of many of Toronto’s most prominent citizens from earlier days. Among those interred there are reformer Robert Baldwin, politician Edward Blake, police chiefs Francis Collier Draper and H.J. Grasset, whiskey magnates George and William Gooderham Sr., engineer and railway builder Casimir Gzowski, journalist Peter Gzowski, historian and journalist Goldwin Smith, and Ontario Premier John P. Robarts. The cemetery’s chapel, the Chapel of St. James-the-Less, was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1990. Holy Blossom Cemetery on Pape Avenue Holy Blossom Cemetery was the first Jewish cemetery established in Toronto. It was opened in 1849 on Pape Avenue (then called Centre Road) near Gerrard Street, in what was then still a predominantly rural area. It served Toronto’s Jewish community for decades, but eventually became full, and was closed to new burials in the 1930s. It contains the graves of most of the founders of Toronto’s Jewish community. Holy Blossom Temple took over the operation of the cemetery when the synagogue was founded in 1856, and continues to responsible for its upkeep. Toronto Necropolis As Toronto expanded northward and westward, the land that Potter’s Field was on became attractive to the property speculators of the day, and pressure grew for the cemetery to be closed and the bodies moved to a different location. In 1850, 15 acres were purchased on land overlooking the Don Valley, east of Sumach, and just to the north of the “plank road” (Winchester Street) which led to a crossing over the Don River. The location was remote from where people lived, yet relatively accessible. The new cemetery was given the name Toronto Necropolis. The name stems from the Greek word nekropolis, meaning “city of the dead.” The process of moving bodies from Potter’s Field began later in the decade, after the cemetery was laid out, and continued until 1874. Many of those moved were transported, in consultation with their surviving family members, along with their grave markers to new graves in the Necropolis. However, there were also many remains in Potter’s field which could not be identified, or for which no one took responsibility. Unclaimed bodies were moved either to the Necropolis, or to the just-opened Mount Pleasant Cemetery. As the Globe noted when Mount Pleasant officially opened in 1876, “In a mound here lie the bones of about 3,000 persons which could not be identified. The remains of old and young persons of every Christian denomination, coloured and white people alike, here rest together in one common grave.” When the Toronto Necropolis was laid out, care was taken to preserve the natural character of the setting. The cemetery has also been notable for an abundance of trees and shrubs, which provide habitat for birds, squirrels, and other wildlife. Woodpeckers, chickadees, nuthatches, and robins can been seen and heard year-round, and many other kinds of birds pass through. For many years, the Riverdale Zoo was located immediately to the south of the Necropolis, and visitors could sometimes hear the howling of wolves and the roar of lions. The zoo closed in the 1970s, to be replaced by the Riverdale Farm, so now a visitor is more likely to hear the sounds of chickens or cows, and the laughter of children, coming from across Winchester Street. In keeping with its non-sectarian traditions, the Necropolis holds the remains of many Torontonians – more than 50,000 in all – from all walks of life. There are members of the establishment like John Ross Robertson, founder of the Toronto Telegram, and Ralph Day, a mayor of Toronto. George Brown, a prominent politician and founder of the Globe newspaper, is buried here – and so is George Bennett, the employee who shot Brown, and was hanged for his murder. The Underground Railroad brought many Black Americans escaping slavery to Toronto, and many of them found their final resting place in the Necropolis. One of the more prominent monuments in the Necropolis commemorates Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews, two men who were hanged in 1838 for their participation in the 1837 rebellion in Upper Canada. The leader of the 1837 Rebellion, William Lyon Mackenzie, is also buried in the Necropolis. Among those buried in the Necropolis are: Samuel Lount (1791-1838) and Peter Matthews (1789-1838) – Rebels from the Rebellion of 1837. Andrew Porteous (1790-1849) – First person to be buried at Necropolis 1850. Beverly Randolph Snow (1799-1856). Born enslaved he was manumitted in 1829. Snow became an early black entrepreneur and restaurateur in both Washington DC and Toronto. In August 1835 his Epicurean Eating House in Washington was destroyed by a white mob during a race riot subsequently known as the “Snow Riot”. William Lyon Mackenzie (1795-1861) – Radical, newspaper publisher, Toronto’s first mayor and leader of the 1837 Upper Canada Rebellion. Joseph Bloor (1789-1862) – An innkeeper and brewer for whom Toronto’s Bloor Street is named. Wilson Ruffin Abbott (1801-1876) – Black Canadian businessman, landowner, and member of city council. George Brown (1818-1880) – Politician and founder of The Globe newspaper (now The Globe and Mail). David Ward (1817-1881) & Family, English-born settler of Ward’s Island, interred along with four of his five daughters at Plot F-157. David was a fisherman and hotelier for whom Ward’s Island was named. Lost his five surviving daughters to drowning in Lake Ontario on May 11, 1862, in a boating mishap. A son, William, survived. (William’s first wife, Charlotte Ford, also died young, of tuberculosis, and is also interred here.) Thornton Blackburn (1812-1890) and Lucie Blackburn (d. 1895) – Thornton Blackburn was a former slave who made his way to Canada on the “Underground Railroad“ and established the first cab company in Toronto. William Holmes Howland (1844-1893) – Mayor of Toronto. Henry Box Brown (c, 1815-1897) – African American who famously escaped slavery in 1848 by mailing himself in a custom made box from Richmond to Philadelphia. He later became a lecturer and entertainer, spending his last two decades in Toronto. Ned Hanlan (1855-1908) – World-champion oarsman. Hanlan’s Point Beach was named after the family hotel at Hanlan’s Point, built c. 1870 by his father, John, a fisherman-turned-hotelier. Dr. Anderson Ruffin Abbott (1837-1913) – First Canadian-born black surgeon. Albert Jackson (1857-1918) – First Black Letter Carrier in Toronto. John Ross Robertson (1841-1918) – Founder of the Toronto Telegram. William Peyton Hubbard (1842-1935) – Black Toronto city alderman. Arthur Roy Brown (1893-1944) – WWI Flying Ace. Janet Hamilton Neilson (1873-1953) – Pioneering Nurse Who Took Care of Tuberculosis Patients. Joseph Burr Tyrrell (1858-1957) – Discovered that dinosaurs once roamed Alberta’s Bad Lands. Ralph Day (1898-1976) – Toronto mayor from 1938 to 1940. Marion Engel (1933-1985) – Canadian novelist. Allen Yen (1925-1993) – Radio Astronomer. Kay Christie (1911-1994) – Canadian Nursing Sister in Hong Kong during the Japanese Invasion during World War II. One of two Canadian Nursing sisters to have been held as a Prisoner of War. Kosso Eloul (1920-1995) – Black Toronto city alderman. Carol Anne Letheren (1942-2001) – Canadian Olympian. Dora de Pédery-Hunt (1913-2008) – Hungarian-Canadian Sculptor and Medallist William Johnson Stapleton (1916-2008) – Artist. Jack Layton (1950-2011) – Politician (Toronto City Councillor, later leader of the New Democratic Party of Canada). Josef Skvorecky (1924-2012) – Writer and publisher. Bob Davis (1934-2012) – Teacher, writer, social justice activist. Mollie Christie (1913-2013) – Prominent figure in the early days of Toronto’s social welfare services; Founding Executive Director of the Community Information Centre of Metropolitan Toronto. Miriam Garfinkle (1954-2018) – Physician and social justice activist. Related Reading: This article is also available in

Chinese

and

French

and

German.

Related Topics: |