Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Pete Seeger

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pete Seeger | |

|---|---|

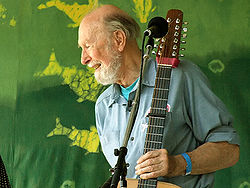

Seeger at the Clearwater Festival 2007.

|

|

| Background information | |

| Born | May 3, 1919 French Hospital, Manhattan, New York |

| Genres | Folk |

| Occupations | Singer-songwriter, activist |

| Instruments | Banjo, guitar, recorder, mandolin, piano, ukulele |

| Years active | 1939–present |

| Labels | Folkways Records Columbia/CBS Records Vanguard Records Sony Kids– Music/SME Records |

| Associated acts | The Weavers, The Almanac Singers, Woody Guthrie, Arlo Guthrie |

| Notable instruments | |

| Banjo, Twelve-string guitar | |

Peter "Pete" Seeger (born May 3, 1919) is an American folk singer and an iconic figure in the mid-twentieth century American folk music revival. A fixture on nationwide radio in the 1940s, he also had a string of hit records during the early 1950s as a member of The Weavers, most notably the 1950 recording of Leadbelly's "Goodnight, Irene", which topped the charts for 13 weeks in 1950.[1] Members of The Weavers were blacklisted during the McCarthy Era. In the 1960s, he re-emerged on the public scene as a prominent singer of protest music in support of international disarmament, civil rights, and for environmental causes.

As a song writer, he is best known as the author or co-author of "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?", "If I Had a Hammer (The Hammer Song)" (composed with Lee Hays of The Weavers), and "Turn, Turn, Turn!", which have been recorded by many artists both in and outside the folk revival movement and are still sung throughout the world. "Flowers" was a hit recording for The Kingston Trio (1962), Marlene Dietrich, who recorded it in English, German and French (1962), and Johnny Rivers (1965). "If I Had a Hammer" was a hit for Peter, Paul & Mary (1962) and Trini Lopez (1963), while The Byrds popularized "Turn, Turn, Turn!" in the mid-1960s, as did Judy Collins in 1964. Seeger was one of the folksingers most responsible for popularizing the spiritual "We Shall Overcome" (also recorded by Joan Baez and many other singer-activists) that became the acknowledged anthem of the 1960s American Civil Rights Movement, soon after folk singer and activist Guy Carawan introduced it at the founding meeting of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960.

Contents |

Seeger was born in French Hospital, Midtown Manhattan. His parents were living with his grandparents in Patterson, New York, from 1918 to 1920. His father, Charles Louis Seeger Jr., was a composer and pioneering ethnomusicologist investigating both American folk and non-Western music. His mother, Constance de Clyver Edson, was a classical violinist and teacher.[2] His parents divorced when Seeger was seven. His stepmother, Ruth Crawford Seeger, was one of the most significant female composers of the twentieth century. His eldest brother, Charles Seeger III, was a radio astronomer, and his next older brother, John Seeger, taught for years at the Dalton School in Manhattan. His uncle, Alan Seeger, a noted poet, was killed during the First World War. His half-sister, Peggy Seeger, also a well-known folk performer, was married for many years to British folk singer Ewan MacColl. Half-brother Mike Seeger went on to form the New Lost City Ramblers, one of whose members, John Cohen, was married to Pete's other half-sister, singer Penny Seeger.

In 1943, Pete married Toshi-Aline Åta, whom he credits with being the support that helped make the rest of his life possible. Pete and Toshi have three children: Daniel (an accomplished photographer and filmmaker), Mika, and Tinya–and grandchildren Tao, Cassie, Kitama, Moraya, Penny, and Isabelle. Tao is a folk musician in his own right, singing and playing guitar, banjo and harmonica with the Mammals. Kitama Jackson is a documentary filmmaker who was associate producer of the PBS documentary Pete Seeger: The Power of Song.

Seeger lives in the hamlet of Dutchess Junction in the Town of Fishkill, NY and as well a residence in the town he grew up in Patterson, NY. He remains very active politically as well as maintaining an active lifestyle in the Hudson Valley Region of New York, especially in the nearby City of Beacon, NY. He and Toshi purchased their land in 1949 and lived there first in a trailer, then in a log cabin they built themselves, and eventually in a larger house.[3] Seeger joined the Community Church of New York (a church practicing Unitarian Universalism)[4] and often performs at functions for the Unitarian Universalist Association.[5][6]

Pete Seeger attended the Avon Old Farms boarding school in Connecticut, during which he was selected to attend Camp Rising Sun, the Louis August Jonas Foundation's international summer scholarship program. Though Pete Seeger's parents were both professional musicians, they didn't press him to play an instrument. On his own, Pete gravitated to the ukulele, becoming adept at entertaining his classmates with it, while laying the basis for his subsequent remarkable audience rapport. Pete heard the five-string banjo for the first time at the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville, North Carolina in 1936, while traveling with his father (then a director of Roosevelt's Farm Resettlement program),[7] It changed his life forever. He spent much of the next four years trying to master the instrument.

Seeger enrolled at Harvard College on a partial scholarship, but, as he became increasingly involved with radical politics and folk music, his grades suffered and he lost his scholarship. He dropped out of college in 1938.[8] He dreamed of a career in journalism and also took courses in art. His first musical gig was leading students in folk singing at the Dalton School, where his aunt was principal. He polished his performance skills during summer stint of touring New York State with The Vagabond Puppeteers (Jerry Oberwager, 22; Mary Wallace, 22; and Harriet Holtzman, 23), a traveling puppet theater "inspired by rural education campaigns of post-revolutionary Mexico",[9] One of their shows coincided with a strike by dairy farmers. The group reprised its act in October in New York City. An article in the October 2, 1939 Daily Worker reported on the Puppeteers' six-week tour this way:

During the entire trip the group never ate once in a restaurant. They slept out at night under the stars and cooked their own meals in the open, very often they were the guests of farmers. At rural affairs and union meetings, the farm women would bring –suppers– and would vie with each other to see who could feed the troupe most, and after the affair the farmers would have earnest discussions about who would have the honor of taking them home for the night.

–They fed us too well,– the girls reported. –And we could live the entire winter just by taking advantage of all the offers to spend a week on the farm.–

In the farmers' homes they talked about politics and the farmers– problems, about anti-Semitism and Unionism, about war and peace and social security – –and always,– the puppeteers report, –the farmers wanted to know what can be done to create a stronger unity between themselves and city workers. They felt the need of this more strongly than ever before, and the support of the CIO in their milk strike has given them a new understanding and a new respect for the power that lies in solidarity. One summer has convinced us that a minimum of organized effort on the part of city organizations – unions, consumers– bodies, the American Labor Party and similar groups – can not only reach the farmers but weld them into a pretty solid front with city folks that will be one of the best guarantees for progress.[10]

That fall Seeger took a job in Washington, D.C., assisting Alan Lomax, a friend of his father's, at the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress. Seeger's job was to help Lomax sift through commercial "race" and "hillbilly" music and select recordings that best represented American folk music, a project funded by the music division of the Pan American Union (later the Organization of American States), of whose music division his father, Charles Seeger, was head (1938–53).[11] Lomax also encouraged Seeger's folk singing vocation, and Seeger was soon appearing as a regular performer on Alan Lomax and Nicholas Ray's weekly Columbia Broadcasting show Back Where I Come From (1940–41) alongside of Josh White, Burl Ives, Leadbelly, and Woody Guthrie (whom he had first met at Will Geer's Grapes of Wrath benefit concert for migrant workers on March 3, 1940). Back Where I Come From was unique in having a racially integrated cast, which made news when it performed in March 1941 at a command performance at the White House organized by Eleanor Roosevelt called "An Evening of Songs for American Soldiers",[12] before an audience that included the Secretaries of War, Treasury, and the Navy, among other bigwigs. The show was a success but was not picked up by commercial sponsors for nationwide broadcasting because of its integrated cast. During the war, Seeger also performed on nationwide radio broadcasts by Norman Corwin.

As a self-described "split tenor" (between an alto and a tenor),[14] Pete Seeger was a founding member of two highly influential folk groups: The Almanac Singers and The Weavers. The Almanac Singers, which Seeger co-founded in 1941 with Millard Lampell and Arkansas singer and activist Lee Hays, was a topical group, designed to function as a singing newspaper promoting the industrial unionization movement,[15] racial and religious inclusion, and other progressive causes. Its personnel included, at various times: Woody Guthrie, Bess Lomax Hawes, Baldwin "Butch" Hawes, Sis Cunningham, Josh White, and Sam Gary. As a controversial Almanac singer, the 21-year-old Seeger performed under the stage name "Pete Bowers" in order to avoid compromising his father's government career.

In 1950, the Almanacs were reconstituted as The Weavers, named after the title of a 1892 play by Gerhart Hauptmann about a workers' strike (which contained the lines, "We'll stand it no more, come what may!"). Besides Pete Seeger (performing under his own name), members of the Weavers included charter Almanac member Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, Fred Hellerman, and later, Frank Hamilton, Erik Darling and Bernie Krause. In the atmosphere of the 1950s red scare, the Weavers' repertoire had to be less overtly topical than that of the Almanacs had been, and its progressive message was couched in indirect language–arguably rendering it even more powerful. The Weavers even on occasion performed in tuxedos (unlike the Almanacs, who had dressed informally) and their managers refused to let them perform at political venues. Because of this, the somewhat hokey string orchestra and chorus arrangements on a few of their hit numbers, and, no doubt also because of their considerable, if temporary, financial success, the Weavers incurred criticism from some progressives for supposedly compromising their political integrity. It was a tricky dilemma, but Seeger and the other Weavers felt that the imperative of getting their music and their message out to the widest possible audience amply justified these measures. The Weavers' string of major hits began with "On top of Old Smokey" and an arrangement of Leadbelly's signature waltz, "Goodnight, Irene", which topped the charts for 13 weeks in 1950 and was covered by many other pop singers. On the flip side of "Irene" was the Israeli song "Tzena, Tzena, Tzena". Other Weaver hits included, "So Long It's Been Good to Know You" (by Woody Guthrie), "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" (by Hays, Seeger, and Lead Belly), the South African Zulu song, "Wimoweh" (about "the lion", warrior chief Shaka Zulu), to name a few.

The Weavers's performing career was abruptly halted in 1953 at the peak of their popularity when blacklisting prompted radio stations to refuse to play their records and all their bookings were canceled. They briefly returned to the stage, however, at a sold-out reunion at Carnegie Hall in 1955 and in a subsequent reunion tour, which produced a hit version of Merle Travis's "Sixteen Tons" as well as LPs of their concert performances. "Kumbaya", a Gullah black spiritual dating from slavery days, was also introduced to wide audiences by Pete Seeger and the Weavers (in 1959), becoming a staple of Boy and Girl Scout campfires.

In the late fifties, the Kingston Trio was formed in direct imitation of (and homage to) the Weavers, covering much of the latter's repertoire, though with a more button-down, uncontroversial and mainstream collegiate persona. The Kingston Trio produced another phenomenal succession of Billboard chart hits, and, in its turn spawned a legion of imitators, laying the groundwork for the 1960s commercial folk revival.

In the documentary film Pete Seeger: The Power of Song (2007), Seeger states that he resigned from the Weavers when the three other band members agreed to perform a jingle for a cigarette commercial.

In 1948, Seeger wrote the first version of his now-classic How to Play the Five-String Banjo, a book that many banjo players credit with starting them off on the instrument. He went on to invent the Long Neck or Seeger banjo. This instrument is three frets longer than a typical banjo,is slightly longer than a bass guitar at 25 frets, and is tuned a minor third lower than the normal 5-string banjo. Hitherto strictly limited to the Appalachian region, the five-string banjo became known nationwide as the American folk instrument par excellence, largely thanks to Seeger's championing of and improvements to it. According to an unnamed musician quoted in David King Dunaway's biography, "by nesting a resonant chord between two precise notes, a melody note and a chiming note on the fifth string" Pete Seeger "gentrified" the more percussive traditional Appalachian "frailing" style, "with its vigorous hammering of the forearm and its percussive rapping of the fingernail on the banjo head".[16] Though what Dunaway's informant describes is the age-old droned frailing style, the implication is that Seeger made this more acceptable to mass audiences by omitting some of its percussive complexities, while presumably still preserving the characteristic driving rhythmic quality associated with the style.

From the late 1950s on, Seeger also accompanied himself on the 12-string guitar, an instrument of Mexican origin that had been associated with Lead Belly who had styled himself "the King of the 12-String Guitar." Seeger's distinctive custom-made guitars had a triangular soundhole. He combined the long scale length (approximately 28") and capo-to-key techniques that he favored on the banjo with a variant of drop-D (DADGBE) tuning, tuned two whole steps down with very heavy strings, which he played with thumb and finger picks.[17]

On March 16, 2007, Pete Seeger, his sister Peggy, his brothers Mike and John, his wife Toshi, and other family members spoke and performed at a symposium and concert sponsored by the American Folklife Center in honor of the Seeger family, held at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.,[18] where Pete Seeger had been employed by the Archive of American Folk Song 67 years earlier.

On September 29, 2008, the 89-year-old singer-activist, once banned from commercial TV, made a rare nationwide appearance on the Late Show with David Letterman, singing "Don't say it can't be done, the battle's just begun... take it from Dr. King you too can learn to sing so drop the gun." In September 2008, Appleseed Recordings released At 89, Seeger's first studio album in 12 years. On September 19, Pete Seeger made his first appearance at the 52nd Monterey Jazz Festival, particularly notable because the Festival does not normally feature folk artists.

In 2010, still active at the age of 91, Seeger co-wrote and performed a song "God's Counting on Me, God's Counting on You" with Lorre Wyatt, commenting on the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.[19]

On January 18, 2009, Seeger joined Bruce Springsteen, grandson Tao Rodrguez-Seeger, and the crowd in singing the Woody Guthrie song "This Land Is Your Land" in the finale of Barack Obama's Inaugural concert in Washington, D.C.[20][21] The performance was noteworthy for the inclusion of two verses not often included in the song, one about a "private property" sign the narrator cheerfully ignores, and the other making a passing reference to a Depression-era relief office.[20][22]

On May 3, 2009, at The Clearwater Concert, dozens of musicians gathered in New York at Madison Square Garden to celebrate Seeger's 90th birthday (which was later televised on PBS during the summer),[23] ranging from Dave Matthews, Bruce Springsteen, Tom Morello and Roger McGuinn to Joan Baez, Richie Havens, Tom Paxton, Ramblin' Jack Elliott and Arlo Guthrie. Consistent with Seeger's long-time advocacy for environmental concerns, the proceeds from the event benefited the Hudson River Sloop Clearwater,[24] a non-profit organization created to defend and restore the Hudson River. Seeger's 90th Birthday was also celebrated at The College of Staten Island on May 4.[25]

A number of Pete Seeger celebrations are being organized in Australia including a revival of the musical play about his life ONE WORD WE!, a DVD of his 1963 concert in Melbourne Town Hall, and concerts in folk clubs and folk festivals. One Word WE! was performed at the Tom Mann Theatre in Surry Hills, Sydney, on 12, 13 and 14 June 2009. It was written by Maurie Mulheron, who is also musical director and a performer. Frank Barnes directed.

On April 18, 2009, Pete Seeger performed in front of a small group of Earth Day celebrants at Teachers College in New York City. Among the songs he performed were "This Land is Your Land", "Take it From Dr. King" and "She'll Be Coming 'Round the Mountain."

In 1936, at the age of 17, Pete Seeger joined the Young Communist League (YCL), then at the height of its popularity and influence. In 1942 he became a member of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) itself. He eventually "drifted away" (his words) from the Party in the late 1940s and 1950s.[26]

In the spring of 1941, the twenty-one-year-old Seeger performed as a member of the Almanac Singers along with Millard Lampell, Cisco Houston, Woody Guthrie, Butch and Bess Lomax Hawes, and Lee Hays. Seeger and the Almanacs cut several albums of 78s on Keynote and other labels, Songs for John Doe (recorded in late February or March and released in May, 1941), the Talking Union, and an album each of sea chanteys and pioneer songs. Written by Millard Lampell, Songs for John Doe was performed by Lampell, Seeger, and Hays, joined by Josh White and Sam Gary. It contained lines such as, "It wouldn't be much thrill to die for Du Pont in Brazil", that were sharply critical of Roosevelt's unprecedented peacetime draft (enacted in September, 1940). This anti-war/anti-draft tone reflected the Communist Party line after the 1939 Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which maintained the war was "phony" and a mere pretext for big American corporations to get Hitler to attack Soviet Russia, a line of argument that Seeger has said he believed to be true at the time and which was adhered to by many members of the Young Communist League (YCL), of which he was a member. Though nominally members of the Popular Front, which was allied with Roosevelt and more moderate liberals, the YCL's members were still smarting over the memory of Roosevelt and Churchill's arms embargo to Loyalist Spain (which Roosevelt later called a mistake) and the alliance was fraying in the confusing welter of events.

A June 16, 1941, review in Time magazine, which under its owner Henry Luce had become very interventionist, denounced the Almanacs' John Doe, accusing it of scrupulously echoing what it called "the mendacious Moscow tune" that "Franklin Roosevelt is leading an unwilling people into a J. P. Morgan war". Eleanor Roosevelt, a fan of folk music, reportedly found the album "in bad taste," though President Roosevelt, when the album was shown to him, merely observed, correctly as it turned out, that few people would ever hear it. More alarmist was the reaction of eminent German-born Harvard Professor of Government, Carl Joachim Friedrich an adviser on domestic propaganda to the US military. In a review in the June 1941 Atlantic Monthly, entitled "The Poison in Our System", he pronounced Songs for John Doe "strictly subversive and illegal", "whether Communist or Nazi financed" and "a matter for the attorney general", observing further that "mere" legal "suppression" would not be sufficient to counteract this type of populist poison,[27] the poison being folk music, and the ease with which it could be spread.

At that point, the U.S. had not yet entered the war but was energetically re-arming. African Americans were barred from working in defense plants, a situation that greatly angered both African Americans and white progressives. Black union leaders A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and A. J. Muste began planning a huge march on Washington to protest racial discrimination in war industries and to urge desegregation of the armed forces. The march, which many regard as the first manifestation of the Civil Rights Movement, was canceled after President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 (The Fair Employment Act) of June 25, 1941, barring discrimination in hiring by companies holding federal contracts for defense work. This Presidential act defused black anger considerably, although the US army still refused to desegregate, declining to participate in what it called "social engineering".

Roosevelt's order came three days after Hitler broke the non-aggression pact and invaded the Soviet Union. The Communist Party now immediately directed its members to get behind the draft, and it also forbade participation in strikes for the duration of the war (angering some leftists). Copies of Songs for John Doe were removed from sale, and the remaining inventory destroyed, though a few copies may exist in the hands of private collectors.[28] The Almanac Singers' Talking Union album, on the other hand, was reissued as an LP by Folkways (FH 5285A) in 1955 and is still available. The following year the Almanacs issued Dear Mr. President, an album in support of Roosevelt and the war effort. The title song, "Dear Mr. President", was a solo by Pete Seeger, and its lines expressed his life-long credo:

Now, Mr. President, / We haven't always agreed in the past, I know, / But that ain't at all important now. / What is important is what we got to do, / We got to lick Mr. Hitler, and until we do, / Other things can wait.//

Now, as I think of our great land . . . / I know it ain't perfect, but it will be someday, / Just give us a little time. // This is the reason that I want to fight, / Not 'cause everything's perfect, or everything's right. / No, it's just the opposite: I'm fightin' because / I want a better America, and better laws, / And better homes, and jobs, and schools, / And no more Jim Crow, and no more rules like / "You can't ride on this train 'cause you're a Negro," / "You can't live here 'cause you're a Jew,"/ "You can't work here 'cause you're a union man."//

So, Mr. President, / We got this one big job to do / That's lick Mr. Hitler and when we're through, / Let no one else ever take his place / To trample down the human race. / So what I want is you to give me a gun / So we can hurry up and get the job done.

Seeger's critics, however, have continued to bring up the Almanacs' repudiated Songs for John Doe. In 1942, a year after the John Doe album's brief appearance (and disappearance), the FBI decided that the now-pro-war Almanacs were still endangering the war effort by subverting recruitment. According to the New York World Telegram (Feb. 14, 1942), Carl Friedrich's 1941 article "The Poison in Our System" was printed up as a pamphlet and distributed by the Council for Democracy (an organization that Friedrich and Henry Luce's right hand man, C. D. Jackson, Vice President of Time magazine, had founded "to combat all the nazi, fascist, communist, pacifist" antiwar groups in the United States).[29] and was shown to the Almanac's employers in order to keep them off the air. Coincidentally, defamatory reviews and gossip items appeared in New York newspapers whenever they performed in public, and ultimately the Almanacs had to disband.[30]

Seeger served in the US Army in the Pacific. He was trained as an airplane mechanic, but was reassigned to entertain the American troops with music. Later, when people asked him what he did in the war, he always answered "I strummed my banjo". After returning from service, Seeger and others established People's Songs, conceived as a nationwide organization with branches on both coasts that was designed to "Create, promote and distribute songs of labor and the American People"[31] With Pete Seeger as its director, People's Songs worked for the 1948 presidential campaign of Roosevelt's former Secretary of Agriculture and Vice President, Henry A. Wallace, who ran as a third party candidate on the Progressive Party ticket. Despite having attracted enormous crowds nationwide, however, Wallace only won in New York City, and, in the red-baiting frenzy that followed, he was excoriated (as Roosevelt had not been) for accepting the help in his campaign of Communists and fellow travelers such as Seeger and singer Paul Robeson.[32]

Seeger had been a fervent supporter of the Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War. In 1943, with Tom Glazer and Bess and Baldwin Hawes, he recorded an album of 78s called Songs of the Lincoln Battalion on Moe Asch's Stinson label. This included such songs as "There's a Valley in Spain called Jarama", and "Viva la Quinta Brigada". In 1960, this collection was re-issued by Moe Asch as one side of a Folkways LP called Songs of the Lincoln and International Brigades. On the other side was a reissue of the legendary Six Songs for Democracy (originally recorded in Barcelona in 1938 while bombs were falling), performed by Ernst Busch and a chorus of members of the Thlmann Battalion, made up of refugees from Nazi Germany. The songs were: "Moorsoldaten" ("Peat Bog Soldiers", composed by political prisoners of German concentration camps), "Die Thaelmann-Kolonne", "Hans Beimler", "Das Lied Von Der Einheitsfront" ("Song Of The United Front", written by Hans Eisler and Bertold Brecht), "Der Internationalen Brigaden" ("Song Of The International Brigades"), and "Los cuatro generales" ("The Four Generals", known in English as "The Four Insurgent Generals").

In the 1950s and, indeed, consistently throughout his life, Seeger continued his support of civil and labor rights, racial equality, international understanding, and anti-militarism (all of which had characterized the Wallace campaign) and he continued to believe that songs could help people achieve these goals. With the ever-growing revelations of Stalin's atrocities and the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, however, he became increasingly disillusioned with Soviet Communism. In his PBS biography, Seeger said he "drifted away" from the CPUSA beginning in 1949 but remained friends with some who did not leave it, though he argued with them about it.[33][34]

On August 18, 1955, Seeger was subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Alone among the many witnesses after the 1950 conviction and imprisonment of the Hollywood Ten for contempt of court, Seeger refused to plead the Fifth Amendment (which asserted that his testimony might be self incriminating) and instead (as the Hollywood Ten had done) refused to name personal and political associations on the grounds that this would violate his First Amendment rights: "I am not going to answer any questions as to my association, my philosophical or religious beliefs or my political beliefs, or how I voted in any election, or any of these private affairs. I think these are very improper questions for any American to be asked, especially under such compulsion as this."[35] Seeger's refusal to testify led to a March 26, 1957 indictment for contempt of Congress; for some years, he had to keep the federal government apprised of where he was going any time he left the Southern District of New York. He was convicted in a jury trial of contempt of court in March 1961, and sentenced to 10 years in jail (to be served simultaneously), but in May 1962 an appeals court ruled the indictment to be flawed and overturned his conviction.[36]

In 1960, the San Diego school board told him that he could not play a scheduled concert at a high school unless he signed an oath pledging that the concert would not be used to promote a communist agenda or an overthrow of the government. Seeger refused, and the American Civil Liberties Union obtained an injunction against the school district, allowing the concert to go on as scheduled. In February 2009 the San Diego School District officially extended an apology to Seeger for the actions of their predecessors.[37]

A longstanding opponent of the arms race and of the Vietnam War, Seeger satirically attacked then-President Lyndon Johnson with his 1966 recording, on the album Dangerous Songs!?, of Len Chandler's children's song, "Beans in My Ears". Beyond Chandler's lyrics, Seeger said that "Mrs. Jay's little son Alby" had "beans in his ears", which, as the lyrics imply,[38] ensures that a person does not hear what is said to them. To those opposed to continuing the Vietnam War the phrase implied that "Alby Jay" was a loose pronunciation of Johnson's nickname "LBJ", and sarcastically suggested "that must explain why he doesn't respond to the protests against his war policies".

Seeger attracted wider attention starting in 1967 with his song "Waist Deep in the Big Muddy", about a captain – referred to in the lyrics as "the big fool" – who drowned while leading a platoon on maneuvers in Louisiana during World War II. In the face of arguments with the management of CBS about whether the song's political weight was in keeping with the usually light-hearted entertainment of the Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour, the final lines were "Every time I read the paper/those old feelings come on/We are waist deep in the Big Muddy and the big fool says to push on." The lyrics could be interpreted as an allegory of Johnson as the "big fool" and the Vietnam War as the foreseeable danger. Although the performance was cut from the September 1967 show,[39] after wide publicity[40] it was broadcast when Seeger appeared again on the Smothers' Brothers show in the following January.[41]

Inspired by Woody Guthrie, whose guitar was labeled "This machine kills fascists,"photo Seeger's banjo was emblazoned with the motto "This Machine Surrounds Hate and Forces It to Surrender."photo

Seeger is involved in the environmental organization Hudson River Sloop Clearwater, which he co-founded in 1966. This organization has worked since then to highlight pollution in the Hudson River and worked to clean it. As part of that effort, the sloop Clearwater was launched in 1969 with its inaugural sail down from Maine to South Street Seaport Museum in New York City, and thence to the Hudson River.[42] Amongst the inaugural crew was Don McLean, who co-edited the book Songs and Sketches of the First Clearwater Crew, with sketches by Thomas B. Allen for which Seeger wrote the foreword...[43] Seeger and McLean sang "Shenandoah" on the 1974 Clearwater album. The sloop regularly sails the river with volunteer and professional crew members, primarily conducting environmental education programs for school groups. The Great Hudson River Revival (aka Clearwater Festival) is an annual two-day music festival held on the banks of the Hudson at Croton Point Park. This festival grew out of early fundraising concerts arranged by Seeger and friends to raise money to pay for Clearwater's construction.

Seeger wrote and performed "That Lonesome Valley" about the then-polluted Hudson River in 1969, and his band members also wrote and performed songs commemorating the Clearwater.

To earn money during the blacklist period of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Seeger had gigs as a music teacher in schools and summer camps and traveled the college campus circuit. He also recorded as many as five albums a year for Moe Asch's Folkways Records label. As the nuclear disarmament movement picked up steam in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Seeger's anti-war songs, such as, "Where Have All the Flowers Gone?" (co-written with Joe Hickerson), "Turn, Turn, Turn", adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes, and "The Bells of Rhymney" by the Welsh poet Idris Davies [44] (1957), gained wide currency. Seeger also was closely associated with the 1960s Civil Rights movement and in 1963 helped organize a landmark Carnegie Hall Concert, featuring the youthful Freedom Singers, as a benefit for the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. This event and Martin Luther King's March on Washington in August of that year, in which Seeger and other folk singers participated, brought the Civil Rights anthem "We Shall Overcome" to wide audiences. A version of this song, submitted by Zilphia Horton of Highlander, had been published in Seeger's People's Songs Bulletin as early as in 1947.

By this time Seeger was a senior figure in the 1960s folk revival centered in Greenwich Village, as a longtime columnist in Sing Out!, the successor to the People's Songs Bulletin, and as a founder of the topical Broadside magazine. To describe the new crop of politically committed folk singers, he coined the phrase "Woody's children", alluding to his associate and traveling companion, Woody Guthrie, who by this time had become a legendary figure. This urban folk revival movement, a continuation of the activist tradition of the thirties and forties and of People's Songs, used adaptations of traditional tunes and lyrics to effect social change, a practice that goes back to the Industrial Workers of the World or Wobblies' Little Red Song Book, compiled by Swedish-born union organizer Joe Hill (1879–1915). (The Little Red Song Book had been a favorite of Woody Guthrie's, who was known to carry it around.)

Pete Seeger made two tours of Australia, the first in 1963. At the time of this tour, his single "Little Boxes" (written by Malvina Reynolds) was number one in the nation's Top 40s. In 1993 the Australian singer/playwright Maurie Mulheron assembled a musical biography of Seeger's, and friends', work in a stage production One Word We. It enjoyed a long and sold-out season at the New Theatre in the inner Sydney suburb of Newtown. It was reprised in 2000 and 2009, and the company has also taken the show on tour to folk festivals at Maleny and Woodford in Queensland, and Port Fairy in Victoria.

The long television blacklist of Seeger began to end in the mid-1960s when he hosted a regionally broadcast, educational folk-music television show, Rainbow Quest. Among his guests were Johnny Cash, June Carter, Reverend Gary Davis, Mississippi John Hurt, Doc Watson, The Stanley Brothers, Elizabeth Cotten, Patrick Sky, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Tom Paxton, Judy Collins, Donovan, Richard Faria and Mimi Faria, Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee, Mamou Cajun Band, Bernice Johnson Reagon, The Beers Family, Roscoe Holcomb, Malvina Reynolds, and Shawn Phillips. Thirty-nine[33] hour-long programs were recorded at WNJU's Newark studios in 1965 and 1966, produced by Seeger and his wife Toshi, with Sholom Rubinstein.

An early booster of Bob Dylan, Seeger, who was on the board of directors of the Newport Folk Festival, became upset over the extremely loud and distorted electric sound that Dylan, instigated by his manager Albert Grossman, also a Folk Festival board member, brought into the 1965 Festival during his performance of "Maggie's Farm". Tensions between Grossman and the other board members were running very high (at one point reportedly there was a scuffle and blows were briefly exchanged between Grossman and board member Alan Lomax).[45] There are several versions of what happened during Dylan's performance and some claimed that Pete Seeger tried to disconnect the equipment.[46] Seeger has been portrayed by Dylan's publicists as a folk "purist" who was one of the main opponents to Dylan's "going electric", but when asked in 2001 about how he recalled his "objections" to the electric style, he said:

I couldn't understand the words. I wanted to hear the words. It was a great song, "Maggie's Farm," and the sound was distorted. I ran over to the guy at the controls and shouted, "Fix the sound so you can hear the words." He hollered back, "This is the way they want it." I said "Damn it, if I had an axe, I'd cut the cable right now." But I was at fault. I was the MC, and I could have said to the part of the crowd that booed Bob, "you didn't boo Howlin' Wolf yesterday. He was electric!" Though I still prefer to hear Dylan acoustic, some of his electric songs are absolutely great. Electric music is the vernacular of the second half of the twentieth century, to use my father's old term.[47]

In 1982 Seeger performed at a benefit concert for Poland's Solidarity resistance movement. His biographer David Dunaway considers this the first public manifestation of Seeger's decades-long personal dislike of communism in its Soviet form.[48] In the late 1980s Seeger also expressed disapproval of violent revolutions, remarking to an interviewer that he was really in favor of incremental change and that "the most lasting revolutions are those that take place over a period of time."[49] In his autobiography Where Have All the Flowers Gone (1993 and 1997 reissued in 2009), Seeger wrote, "Should I apologize for all this? I think so." He went on to put his thinking in context:

How could Hitler have been stopped? Litvinov, the Soviet delegate to the League of Nations in '36, proposed a worldwide quarantine but got no takers. For more on those times check out pacifist Dave Dellinger's book, From Yale to Jail...[50]. At any rate, today I'll apologize for a number of things, such as thinking that Stalin was merely a "hard driver" and not a supremely cruel misleader". I guess anyone who calls himself a Christian should be prepared to apologize for the Inquisition, the burning of heretics by Protestants, the slaughter of Jews and Muslims by Crusaders. White people in the U.S.A ought to apologize for stealing land from Native Americans and enslaving blacks. Europeans could apologize for worldwide conquests, Mongolians for Ghengis Khan. And supporters of Roosevelt could apologize for his support of Somoza, of Southern White Democrats, of Franco Spain, for putting Japanese Americans in concentration camps. Who should my granddaughter Moraya apologize to? She's part African, part European, part Chinese, part Japanese, part Native American. Let's look ahead.[51][52]

In a 1995 interview, however, he insisted that "I still call myself a communist, because communism is no more what Russia made of it than Christianity is what the churches make of it."[53]

In recent years, as the aging Seeger began to garner awards and recognition for his life-long activism, he also found himself attacked once again for his opinions and associations of the 1930s and '40s. In 2006, David Boaz – Voice of America and NPR commentator and president of the Libertarian Cato Institute – wrote an opinion piece in The Guardian, entitled "Stalin's Songbird" in which he excoriated The New Yorker and The New York Times for lauding Seeger. He characterized Seeger as "someone with a longtime habit of following the party line" who had only "eventually" parted ways with the CPUSA. In support of this view, he quoted lines from the Almanac Singers' May 1941 Songs for John Doe, contrasting them darkly with lines supporting the war from Dear Mr. President, issued in 1942, after the USA had entered the war.[54][55]

In 2007, in response to criticism from a former banjo student – historian Ron Radosh, who was once a Trotskyite and now writes for the conservative National Review – Seeger wrote a song condemning Stalin, "Big Joe Blues"[56]: "I'm singing about old Joe, cruel Joe. / He ruled with an iron hand. /He put an end to the dreams / Of so many in every land. / He had a chance to make / A brand new start for the human race. / Instead he set it back / Right in the same nasty place. / I got the Big Joe Blues. / Keep your mouth shut or you will die fast. / I got the Big Joe Blues. / Do this job, no questions asked. / I got the Big Joe Blues."[57] The song was accompanied by a letter to Radosh, in which Seeger stated, "I think you–re right, I should have asked to see the gulags when I was in U.S.S.R [in 1965]".[52]

The banjo-playing narrator of John Updike's 1998 short story "Licks of Love in the Heart of the Cold War", who is sent by the US government as a "cultural ambassador" to the Soviet Union, confesses himself an ardent fan of Pete Seeger and the Weavers, whom some in the U.S. have branded as a traitor.[58]

1955 "The Folksinger's Guitar Guide (Instruction) (Folkways Records)

| Release Date | Album Title | Record Label |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | American Favorite Ballads, The Complete Collection Vol.1-5 | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 2009 | "Pete Seeger at Bard College" credited to "Ono Okoy and the Banshees," a student performance art group dedicated to "preserving the footsteps of Pete Seeger" by singing folk music and recording his footsteps. | Appleseed Records |

| 2008 | Pete Seeger At 89 | Appleseed Records |

| 2007 | American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 5 | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 2006 | American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 4 | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 2004 | American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 3 | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 2003 | American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 2 | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 2002 | American Favorite Ballads, Vol. 1 | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 2000 | American Folk, Game and Activity Songs | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1998 | Headlines and Footnotes: A Collection of Topical Songs | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1998 | If I Had a Hammer: Songs of Hope and Struggle | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1998 | Birds, Beasts, Bugs and Fishes (Little and Big) | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1993 | Darling Corey/Goofing-Off Suite | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1992 | American Industrial Ballads | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1991 | Abiyoyo and Other Story Songs for Children | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1990 | Folk Songs for Young People | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1990 | American Folk Songs for Children | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1989 | Traditional Christmas Carols | Smithsonian Folkways |

| 1980 | God Bless the Grass | Folkways Records |

| 1979 | Circles & Seasons | Warner Bros Records |

| 1974 | Banks of Marble and Other Songs | Folkways Records |

| 1968 | Wimoweh and Other Songs of Freedom and Protest | Folkways Records |

| 1966 | Dangerous Songs!? | Columbia Records |

| 1966 | God Bless The Grass | Columbia Records |

| 1964 | Songs of Struggle and Protest, 1930-50 | Folkways Records |

| 1964 | Broadsides - Songs and Ballads | Folkways Records |

| 1962 | 12-String Guitar as Played by Lead Belly | Folkways Records |

| 1960 | Champlain Valley Songs | Folkways Records |

| 1959 | American Play Parties | Folkways Records |

| 1958 | Gazette, Vol. 1 | Folkways Records |

| 1957 | American Ballads | Folkways Records |

| 1956 | With Voices Together We Sing | Folkways Records |

| 1956 | Love Songs for Friends and Foes | Folkways Records |

| 1955 | Bantu Choral Folk Songs | Folkways Records |

| 1954 | How to Play a 5-String Banjo (instruction) | Folkways Records |

| 1954 | The Pete Seeger Sampler | Folkways Records |

In 1998 Appleseed Records issued a double-CD tribute album: Where Have All the Flowers Gone: the Songs of Pete Seeger, which included readings by Studs Terkel and songs by Billy Bragg, Jackson Browne, Eliza Carthy, Judy Collins, Bruce Cockburn, Donovan, Ani DiFranco, Dick Gaughan, Nanci Griffith, Richie Havens, Indigo Girls, Roger McGuinn, Holly Near, Odetta, Tom Paxton, Bonnie Raitt, Martin Simpson, and Bruce Springsteen, among others.

In 2001, Appleseed release "If I Had a Song: The Songs of Pete Seeger, Vol. 2". In 2003, it issued the double-CD Seeds: The Songs of Pete Seeger, Volume 3, the final set in its trilogy of releases celebrating Seeger–s music.

In April 2006 Bruce Springsteen released a collection of folk songs associated with Seeger's repertoire, titled, We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions (which some reviewers noted that, oddly, contained no songs actually composed by Seeger). Springsteen and his band also toured to sellout crowds in a series of concerts based on those sessions. He had previously performed the Seeger staple, "We Shall Overcome," on Where Have All the Flowers Gone.

In the 1970s Harry Chapin released a song dedicated to Seeger called "Old Folkie".

Seeger has been the recipient of many awards and recognitions throughout his career, including :

| This section is a candidate to be copied to Wikiquote using the Transwiki process. |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Pete Seeger |

Jim Musselman (founder of Appleseed Recordings), longtime friend and record producer for Pete Seeger:

Raffi on his concert video "Raffi on Broadway" during the introduction of May There Always Be Sunshine:

"And this song is the one that I first heard Pete Seeger singing. And he tells me that it was written by a four-year-old boy in Russia. And it's just got four lines and it's been translated into a number of languages."

|

|

Constructs such as ibid. and loc. cit. are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Pete Seeger |

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions