Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Osceola

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Osceola | |

|---|---|

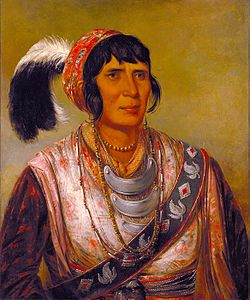

Osceola by George Catlin

|

|

| Tribe | Seminole |

| Born | 1804 Tallassee, Alabama |

| Died | January 1838 (aged 33–34) Fort Moultrie |

| Native name | Asi-yahola |

| Nickname(s) | Billy Powell |

| Cause of death | malaria |

| Resting place | Fort Moultrie |

Osceola (1804 – January 30, 1838) was an influential leader with the Seminole in Florida. Osceola led a small band of warriors in the Seminole resistance during the Second Seminole War when the United States tried to remove the Seminoles from their lands. He exercised a great deal of influence on Micanopy, the highest-ranking chief of the Seminoles.[1][dead link]

Osceola was named Billy Powell at birth in 1804 in the village of Tallassee, Alabama around current Macon County. "The people in the town of Tallassee, where Billy Powell, (later named Osceola) was born, were mixed-blood Native American/English/Irish/Scottish, and some were black. Billy was all of these."[2] His mother Polly Coppinger was daughter of Ann McQueen, who was part Muscogee and part Scottish.[citation needed] Many sources, including the Seminole, state that Osceola's father was an English trader William Powell.[3]

Osceola's mixed white ancestry would have been an anomaly at the time because the Seminoles strictly forbade intermarriage with whites.[4] Osceola's great-grandfather was James McQueen, who was Scottish and the first white man to trade with the Creeks in Alabama in 1714. He stayed in the area as a trader and became closely involved with the Creek. James McQueen's daughter Ann married Jose Coppinger. Their daughter Polly was the mother of Osceola. Osceola claimed to be a full-blood Muscogee.[citation needed]

In 1814 Osceola and his mother moved from Alabama to Florida together with other Creeks. In adulthood he received his name; Osceola (pronounced /ÉsioÊŠlÉ/ or /oÊŠseÉoÊŠlÉ/) is an anglicised form of the Creek asi-yahola (pronounced [asi jahola]); the combination of asi, the ceremonial black drink made from the yaupon holly, and yahola, meaning shout or shouter.[3][5]

Contents |

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (December 2006) |

In 1832, a few Seminole chiefs signed the Treaty of Payne's Landing, by which they agreed to give up their Florida lands in exchange for lands west of the Mississippi River. Five of the most important of the Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy of the Alachua Seminoles, did not agree to the move. In retaliation, Native American agent Wiley Thompson declared that those chiefs were removed from their positions. As relations with the Seminoles deteriorated, Thompson forbade the sale of guns and ammunition to the Seminoles. Osceola, a young warrior beginning to rise to prominence, was particularly upset by the ban, as he felt it equated Seminoles with slaves.

Osceola had two wives and at least five children. One of his wives was a black woman, and he fiercely opposed the enslavement of free peoples.(Katz 1986) In spite of this, Thompson considered Osceola to be a friend, and gave him a rifle. Later, though, when Osceola quarreled with Thompson, Thompson had him locked up at Fort King for a night. The next day, to get released, Osceola agreed to abide by the Treaty of Payne's Landing and to bring his followers in. On December 28, 1835 Osceola and his followers ambushed and killed Wiley Thompson and six others outside of Fort King.[6]

On October 21, 1837, on the orders of U.S. General Thomas Sidney Jesup, Osceola was captured when he arrived for supposed truce negotiations in Fort Payton. He was imprisoned at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Florida. Osceola's capture by deceit caused a national uproar. General Jesup and the administration were condemned.[citation needed] That December, Osceola and other Seminole prisoners were moved to Fort Moultrie, South Carolina. They were visited by townspeople.

George Catlin and other prominent painters met him and persuaded him to pose. Robert J. Curtis painted an oil portrait of Osceola as well. These pictures inspired a number of other prints, engravings, and even cigar store figures. Afterward numerous landmarks, including Osceola Counties in Florida, Iowa, and Michigan, were named after him, along with Florida's Osceola National Forest.

Osceola died of malaria on January 30, 1838, less than three months after his capture.[2] He was buried with military honors at Fort Moultrie.

|

|

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2009) |

After his death, army doctor Frederick Weedon persuaded Seminoles to allow him to make a death mask of Osceola, as was a custom at the time. Later he removed Osceola's head and embalmed it. For some time, he kept it and a number of personal objects Osceola had given him. Captain Pitcairn Morrison took the mask alongside other objects that had belonged to Osceola and sent it to an army officer in Washington. By 1885, the death mask and some of the belongings ended up in the anthropology collection of the Smithsonian Institution, where they are still held. Later, Weedon gave the head to his son-in-law Daniel Whitehurst who, in 1843, sent it to Valentine Mott, a New York physician. Mott placed it in his collection at the Surgical and Pathological Museum. It was presumably lost when a fire destroyed the museum in 1866.

In 1966, Miami businessman Otis W. Shriver claimed he had dug up Osceola's grave and put his bones in a bank vault to rebury them at a tourist site in the Rainbow Springs. Shriver traveled around the state in 1967 to gather support for his project. Archaeologists later proved that Shriver had dug up animal remains; Osceola's body was still in its coffin. Some of Osceola's belongings remain in the possession of the Weedon family, while others have disappeared.

The Seminole Nation bought Osceola's bandolier and other personal items from a Sotheby's auction in 1979. Because of his significance, people have created forgeries of Osceola's items, and rumors persist about his head.

|

|

This section does not cite any references or sources. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2007) |

In the pilot episode of the short-lived science fiction television series Freakylinks, the characters investigate the purchase of Osceola's severed head on the black market.

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions