Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Abbie Hoffman

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abbie Hoffman | |

|---|---|

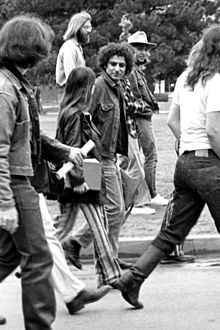

Abbie Hoffman visiting the University of Oklahoma to protest the Vietnam War |

|

| Born | November 30, 1936 Worcester, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | April 12, 1989 (aged 52) New Hope, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Other names | FREE!, Barry Freed |

| Occupation | Social and political activist, writer |

| Influenced by | Marshall McLuhan, Che Guevara, Herbert Marcuse, Abraham Maslow, Groucho Marx, John Lennon, George Metesky, the Diggers, the Cuban Revolution, counterculture of the 1960s, John Sinclair |

| Influenced | Bob Black, the Yippies, opposition to the Vietnam War, Dana Beal, Jello Biafra, Steve Conliff, Jonah Raskin, CrimethInc. |

Abbot Howard "Abbie" Hoffman (November 30, 1936 – April 12, 1989) was an American social and political activist who co-founded the Youth International Party ("Yippies").

Hoffman was arrested and tried for conspiracy and inciting to riot as a result of his role in protests that led to violent confrontations with police during the 1968 Democratic National Convention, along with Jerry Rubin, David Dellinger, Tom Hayden, Rennie Davis, John Froines, Lee Weiner and Bobby Seale. The group was known collectively as the "Chicago Eight"; when Seale's prosecution was separated from the others, they became known as the Chicago Seven. While initially convicted of intent to incite a riot, the verdicts were overturned on appeal.

Hoffman came to prominence in the 1960s, and continued practicing his activism in the 1970s, and has remained a symbol of the youth rebellion and radical activism of that era.[1]

Contents |

Hoffman was born in Worcester, Massachusetts to John Hoffman and Florence Schamberg, who were of Jewish descent. Hoffman was raised in a middle class household, and was the oldest of three children. On June 3, 1954, the 17-year-old Hoffman landed his first arrest, being charged with driving without a license. In his Sophomore year, Hoffman was expelled from Classical High School, Worcester Massachusetts after a disagreement with an English teacher, after which he attended Worcester Academy , graduating in 1955. He then enrolled in Brandeis University, completing his B.A. in Psychology in 1959. At Brandeis, he studied under professors such as noted psychologist Abraham Maslow, often considered the father of humanistic psychology.[2] Hoffman later enrolled at University of California, Berkeley in attempts to earn a Master's Degree in Psychology. He later dropped out to marry his girlfriend, Sheila Karklin, who had recently became pregnant.

Prior to his days as a leading member of the Yippie movement, Hoffman was involved with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and organized "Liberty House", which sold items to support the Civil Rights Movement in the southern United States. During the Vietnam War, Hoffman was an anti-war activist, who used deliberately comical and theatrical tactics, such as organizing a mass demonstration in which over 50,000 people would attempt to use psychic energy to levitate The Pentagon until it would turn orange and begin to vibrate, at which time the war in Vietnam would end.[3] Hoffman's symbolic theatrics were successful at convincing many young people to become more active in the politics of the time.[3]

Another one of Hoffman's well-known protests was on August 24, 1967, when he led members of the movement to the gallery of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). The protesters threw fistfuls of dollars down to the traders below, some of whom booed, while others began to scramble frantically to grab the money as fast as they could. [4] Accounts of the amount of money that Hoffman and the group tossed was said to be as little as $30 to $300.[5] Hoffman claimed to be pointing out that, metaphorically, that's what NYSE traders "were already doing." "We didn't call the press", wrote Hoffman, "at that time we really had no notion of anything called a media event." The press was quick to respond and by evening the event was reported around the world. Since that incident, the stock exchange has spent $20,000 to enclose the gallery with bulletproof glass.[6]

Hoffman was arrested and tried for conspiracy and inciting to riot as a result of his role in anti-Vietnam War protests, which were met by a violent police response during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.[7] He was among the group that came to be known as the Chicago Seven (originally known as the Chicago Eight), which included fellow Yippie Jerry Rubin, David Dellinger, Rennie Davis, John Froines, Lee Weiner, future California state senator Tom Hayden and Black Panther Party co-founder Bobby Seale (before his trial was severed from the others).

The Chicago Eight became the "Chicago Seven" when Bobby Seale was ordered to be bound, gagged and tried separately by Judge Hoffman after repeated requests to represent himself in court.

Presided over by Judge Julius Hoffman (no relation to Abbie, which Abbie joked about throughout the trial), Abbie Hoffman's courtroom antics frequently grabbed the headlines; one day, defendants Hoffman and Rubin appeared in court dressed in judicial robes, while on another day, Hoffman was sworn in as a witness with his hand giving the finger. Judge Hoffman became the favorite courtroom target of the Chicago Seven defendants, who frequently would insult the judge to his face.[8] Abbie Hoffman told Judge Hoffman "you are a 'shande fur de Goyim' [disgrace in front of the gentiles]. You would have served Hitler better." He later added that "your idea of justice is the only obscenity in the room."[8] Both Davis and Rubin told the Judge "this court is bullshit." When Abbie was asked in what state he resided, he replied the "state of mind of my brothers and sisters".

Other celebrities were called as "cultural witnesses" including Allen Ginsberg, Phil Ochs, Arlo Guthrie, Norman Mailer and others. Abbie closed the trial with a speech in which he quoted Abraham Lincoln, making the claim that the President himself, if alive today, would also be arrested in Chicago's Lincoln Park.

On February 18, 1970, Hoffman and four of the other defendants (Rubin, Dellinger, Davis, and Hayden) were found guilty of intent to incite a riot while crossing state lines. All seven defendants were found not guilty of conspiracy. At sentencing, Hoffman suggested the judge try LSD and offered to set him up with "a dealer he knew in Florida" (the judge was known to be headed to Florida for a post-trial vacation). Each of the five was sentenced to five years in prison and a $5,000 fine.[9]

However, all convictions were subsequently overturned by the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals.

At Woodstock in 1969, Hoffman interrupted The Who's performance to attempt a protest speech against the jailing of John Sinclair of the White Panther Party. He grabbed a microphone and yelled, "I think this is a pile of shit while John Sinclair rots in prison ..." The Who's guitarist, Pete Townshend, was adjusting his amplifier between songs and turned to look at Hoffman over his right shoulder. Townshend ran with his Gibson SG and rammed it into the middle of Hoffman's upper back. Hoffman turned with mouth gaping, back arched, with one hand trying to reach the injury as Townshend, disgruntled and yelling "Fuck off! Fuck off my fucking stage,"[10] put a hand in Hoffman's face and shoved him backwards to stage right. Townshend then said, "I can dig it." The rest of the band looked at one another, not sure what was going to happen next. Townshend, frustrated by the interruption, windmilled into the next song ("Do You Think It's Alright"). The band regained composure and followed. After that song, Townshend walked over to Hoffman, who was sitting on the right hand side of the stage with his arms around his knees. Townshend leaned over and said something to him, and gave him a smack up behind the head. Townshend later said that while he actually agreed with Hoffman on Sinclair's imprisonment, he would have knocked him offstage regardless of the content of his message, given that Hoffman had violated the "sanctity of the stage," i.e., the right of the band to perform uninterrupted by distractions not relevant to the actual show. The incident took place during a camera change, and was not captured on film. The audio of this incident, however, can be heard on the The Who's box set, Thirty Years of Maximum R&B (Disc 2, Track 20, "Abbie Hoffman Incident").

In his autobiography, Soon To Be A Major Motion Picture, Hoffman wrote that the incident played out like this:

If you ever heard about me in connection with the festival it was not for playing Florence Nightingale to the flower children. What you heard was the following: "Oh, him, yeah, didn't he grab the microphone, try to make a speech when Peter Townshend cracked him over the head with his guitar?" I've seen countless references to the incident, even a mammoth mural of the scene. What I've failed to find was a single photo of the incident. Why? Because it didn't really happen.

I grabbed the microphone all right and made a little speech about John Sinclair, who had just been sentenced to ten years in the Michigan State Penitentiary for giving two joints of grass to two undercover cops, and how we should take the strength we had at Woodstock home to free our brothers and sisters in jail. Something like that. Townshend, who had been tuning up, turned around and bumped into me. A nonincident really. Hundreds of photos and miles of film exist depicting the events on that stage, but none of this much-talked about scene.

In Woodstock Nation, Hoffman mentions the incident, and says he was on a bad LSD trip at the time. Joe Shea, then a reporter for the Times Herald-Record, a Dow Jones-Ottaway newspaper that covered the event on-site, said he saw the incident. He recalled that Hoffman was actually hit in the back of the head by Townshend's guitar and toppled directly into the pit in front of the stage. He doesn't recall any "shove" from Townshend, and discounts both men's accounts.

In 1971, Hoffman published Steal This Book, which advised readers on how to live basically for free. Many of his readers followed Hoffman's advice and stole the book, leading many bookstores to refuse to carry it. He was also the author of several other books, including Vote!, co-written with Rubin and Ed Sanders.[11] Hoffman was arrested August 28, 1973 on drug charges for intent to sell and distribute cocaine. He always maintained that undercover police agents entrapped him into a drug deal and planted suitcases of cocaine in his office. In the spring of 1974, Hoffman skipped bail, underwent cosmetic surgery to alter his appearance, and hid from authorities for several years.

Despite being "in hiding" during part of this period living in Fineview, New York near Thousand Island Park, a private resort on Wellesley Island on the St. Lawrence River under the name "Barry Freed," he helped coordinate an environmental campaign to preserve the Saint Lawrence River (Save the River organization).[12] During his time on the run, he was also the "travel" columnist for Crawdaddy! magazine. On Sept. 4, 1980, he surrendered to authorities; on the same date, he appeared on a pre-taped edition of ABC-TV's 20/20 in an interview with Barbara Walters. Hoffman received a one-year sentence, but was released after four months.

In November 1986 Hoffman was arrested along with fourteen others, including Amy Carter, the daughter of former President Jimmy Carter, for trespassing at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. The charges stemmed from a protest against the Central Intelligence Agency's recruitment on the UMass campus. Since the university's policy limited campus recruitment to law-abiding organizations, Hoffman asserted in his defense the CIA's lawbreaking activities. The federal district court judge permitted expert witnesses, including former Attorney General Ramsey Clark and a former CIA agent who testified about the CIA's illegal Contra war against the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua in violation of the Boland Amendment.[13]

In three days of testimony, more than a dozen defense witnesses, including Daniel Ellsberg, Ramsey Clark, and former Contra leader Edgar Chamorro, described the CIA's role in more than two decades of covert, illegal and often violent activities. In his closing argument, Hoffman, acting as his own attorney, placed his actions within the best tradition of American civil disobedience. He quoted from Thomas Paine, "the most outspoken and farsighted of the leaders of the American Revolution: "Every age and generation must be as free to act for itself, in all cases, as the ages and generations which preceded it. Man has no property in man, neither has any generation a property in the generations which are to follow."

As Hoffman concluded: "Thomas Paine was talking about this spring day in this courtroom. A verdict of not guilty will say, 'When our country is right, keep it right; but when it is wrong, right those wrongs.'" On April 15, 1987, the jury found Hoffman and the other defendants not guilty.

After his acquittal, Hoffman acted in a cameo appearance in Oliver Stone's later-released anti-Vietnam War movie, Born on the Fourth of July. He essentially played himself in the movie, waving a flag on the ramparts of an administration building during a campus protest that was being teargassed and crushed by state troopers.

In 1987, Hoffman and Jonathan Silvers wrote Steal This Urine Test (published October 5, 1987), which exposed the internal contradictions of the War on Drugs and suggested ways to circumvent its most intrusive measures. He stated, for instance, that Federal Express, which received high praise from management guru Tom Peters for "empowering" workers, in fact subjected most employees to random drug tests, firing any that got a positive result, with no retest or appeal procedure, despite the fact that FedEx chose a drug lab (the lowest bidder) with a proven record of frequent false positive results.[citation needed]

Stone's Born on the Fourth of July was released on December 20, 1989, more than eight months after Hoffman's suicide on April 12, 1989. At the time of his death, Hoffman was at the height of a renewed public visibility, one of the few '60s radicals who still commanded the attention of all kinds of mass media. He regularly lectured audiences about the CIA's covert activities, including assassinations disguised as suicides. His Playboy article (October, 1988) outlining the connections that constitute the "October Surprise," brought that alleged conspiracy to the attention of a wide-ranging American readership for the first time.

In 1960, Hoffman married Sheila Karklin and had two children: Andrew (b. 1960) and Amy (1962–2007), who later went by the name Ilya. They divorced in 1966.

In 1967, Hoffman married Anita Kushner. They had one son, america Hoffman, deliberately named using a lowercase "a" to indicate both patriotism and non-jingoistic intent[14] (america later took the name Allan). Although Abbie and Anita were effectively separated after Abbie became a fugitive starting in 1973 and he subsequently fell in love with Johanna Lawrenson in 1974 while a fugitive, they were not formally divorced until 1980.

His personal life drew a great deal of scrutiny from the Federal Bureau of Investigation. By their own admission, they kept a file on him that was 13,262 pages long.[15]

Hoffman was 52 at the time of his death on April 12, 1989, which was caused by swallowing 150 Phenobarbital tablets. He had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 1980;[16] while he recently changed treatment medications, he claimed in public to have been upset about his elderly mother, Florence's, cancer diagnosis (Jezer, 1993). Hoffman's body was found in his apartment in a converted turkey coop on Sugan Road in Solebury Township, near New Hope, Pennsylvania. At the time of his death, he was surrounded by about 200 pages of his own handwritten notes, many about his own moods.

His death was officially ruled a suicide.[17] As reported by The New York Times, "Among the more vocal doubters at the service today was Mr. Dellinger, who said, 'I don't believe for one moment the suicide thing.' He said he had been in fairly frequent touch with Mr. Hoffman, who had 'numerous plans for the future.'" Yet the same New York Times article reported that the coroner found the residue of about 150 pills and quoted the coroner in a telephone interview saying 'There is no way to take that amount of phenobarbital without intent. It was intentional and self-inflicted.' [17]

A week after Hoffman's death, a thousand friends and relatives gathered for a memorial in Worcester, Massachusetts at Temple Emanuel, the synagogue he attended as a child. Senior Rabbi Norman Mendel officiated. Two of his colleagues from the Chicago Seven conspiracy trial were there: David Dellinger and Jerry Rubin, Hoffman's co-founder of the Yippies, by then a businessman.

As The New York Times reported: "Indeed, most of the mourners who attended the formal memorial at Temple Emanuel here were more yuppie than yippie and there were more rep ties than ripped jeans among the crowd–."

The Times report continued:

Bill Walton, the radical Celtic of basketball renown, told of a puckish Abbie, then underground evading a cocaine charge in the '70s, leaping from the shadows on a New York street to give him an impromptu basketball lesson after a loss to the Knicks. 'Abbie was not a fugitive from justice,' said Mr. Walton. 'Justice was a fugitive from him.' On a more traditional note, Rabbi Norman Mendell said in his eulogy that Mr. Hoffman's long history of protest, antic though much of it had been, was 'in the Jewish prophetic tradition, which is to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.'

| It has been suggested that Abbie Hoffman: American Rebel be merged into this article or section. (Discuss) |

Hoffman's life was dramatized in the 2000 film Steal This Movie!, in which he was portrayed by Vincent D'Onofrio.

In the 1975 work The Illuminatus! Trilogy, Hoffman briefly appears, having a discussion with Apollonius of Tyana.

In the 1987 HBO television movie Conspiracy: The Trial of the Chicago 8, Hoffman was portrayed by Michael Lembeck.

He was portrayed by Richard D'Alessandro in the 1994 movie Forrest Gump speaking against "the war in Viet-fucking-nam" at a protest rally at the Lincoln Memorial Reflecting Pool facing the Washington Monument.

Hank Azaria's voice is heard as the animated Hoffman in the film Chicago 10.

Sacha Baron Cohen has been cast as Hoffman in Steven Spielberg's film The Trial of the Chicago Seven.[18]

Thomas Ian Nicholas portrays Abbie in the 2010 film entitled * "The Chicago 8"

The Mary-Archie Theatre Company in Chicago started the "Abbie Hoffman Died For Our Sins" Theatre Festival in 1988. This festival runs every year for 3 consecutive days as a celebration of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair of 1969. Festival website

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Abbie Hoffman |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

|

|||||

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions