Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

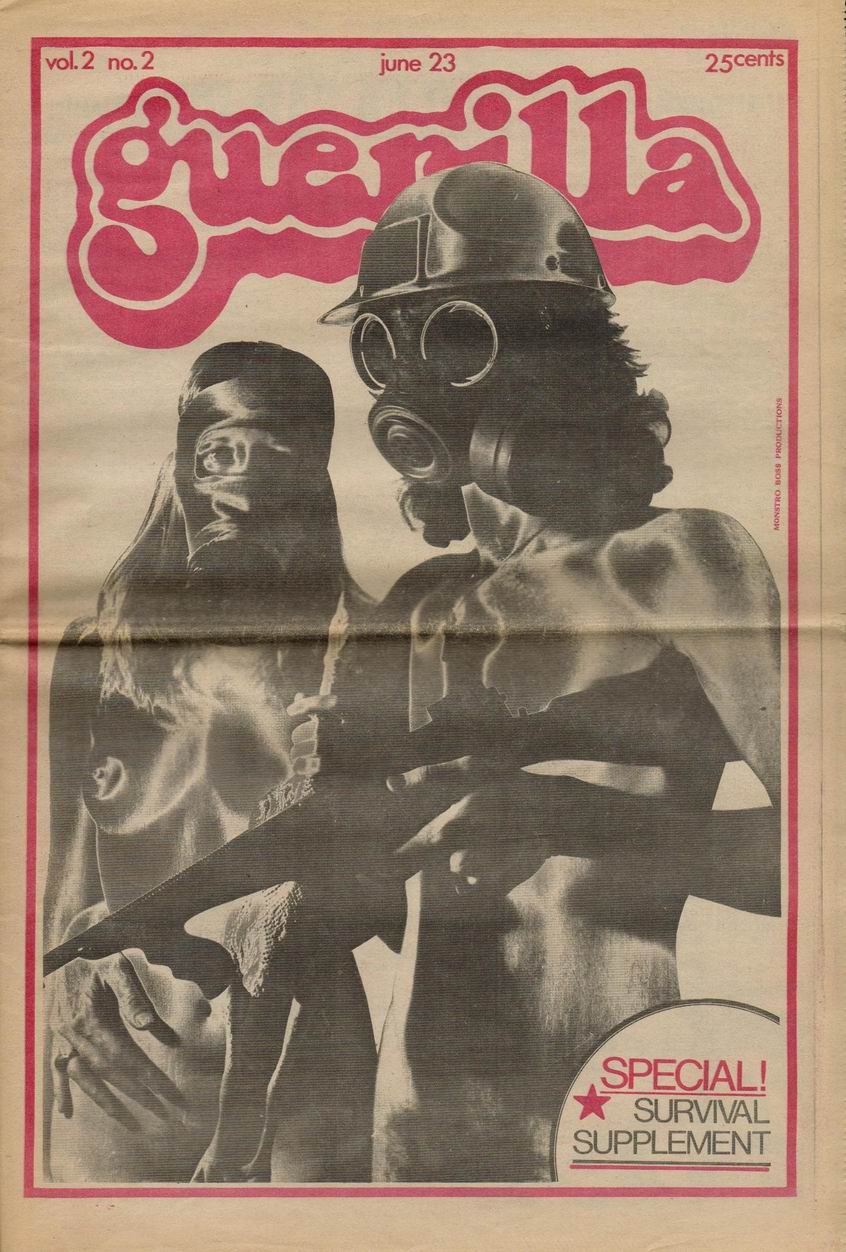

GuerillaIn the heady days of the Toronto counterculture, Guerilla was an ‘underground newspaper’ that attempted to be more political in focus than its rivals, like Harbinger which had a focus on “hippie” issues like sex, drugs and rock’n roll, back-to-the-land, and health food. Guerilla’s founding members included Sharon Fronczak, Bill Saunders, Jim Brophy, and Robert MacDonald, with editor Mike Constable and photographer Al Darlington on staff. The first issue of Guerilla came out in June 1970, one month after the U.S. National Guard killed four students at Kent State University. The paper stressed that it was “trying to break through our passive spectator culture,” and had an anti-capitalist, socialist perspective. But it also included a lively range of regular columnists. There was a “Science for the People” column, a “life at Rochdale College” column, and a legal advice column written by criminal lawyers Clayton Ruby and Paul Copeland. There was also a medical advice column written by Dr. David M. Collins, while economist Mel Watkins and political activist Dave Godfrey wrote book reviews. In an effort to forge a coalition between workers and students, union activist George Longley also wrote a column for Guerilla. As a result, Guerilla quickly became the most-read underground newspaper in Toronto. One of the most controversial of its publications was Guerilla's issue #11 which came out in October 1970 after Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau imposed the War Measures Act, outlawing the Front de Liberation du Quebec (FLQ). Guerilla supported the FLQ and published FLQ documents, along with commentary criticizing Trudeau’s measures. Guerilla became involved in the opposition to the Spadina Expressway (which later was effectively halted), and it had some input in the Wachea park confrontation of 1971 – an effort to establish a tent city for the thousands of hitch-hiking youth passing through Toronto. When City Council opposed this measure, activists set up a tent city on the University of Toronto campus in July 1971. Police shut this down, and Wachea then moved to a site near King and Dufferin. From this experience, Guerilla concluded that it was not possible to organize a transient population for political purposes. Apparently, there was usually tension at the Guerilla office, with splits over issues like women’s empowerment, the highly political focus, the acceptance of advertising from capitalist businesses, etc. By 1971, some of the Guerilla staff and members wanted to focus more on countercultural issues, rather than analyzing political matters. When Guerilla accepted a federal Opportunities For Youth grant in July 1971, the ironies were inescapable, and the split among reformist/radical perspectives became more obvious, even though in 1972 Guerilla was excluded from all federal government grants. The paper was very pro-active around gay liberation issues and devoted considerable coverage to gay activism from late 1970 onwards. Indeed, in 1971 founding members of Guerilla helped to establish and fund a new gay liberation publication called The Body Politic, which quickly gained international attention. By 1972, Guerilla had a lot of competition, with some 21 underground newspapers based in Toronto all vying for readership. Guerilla folded in 1974. Later it emerged that both the FBI and the RCMP had been closely monitoring Guerilla because of its political stance and its popularity among radical Toronto youth. Related Reading: Related Topics:  |

Connect with Connexions

|