Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Eugene V. Debs

Eugene Victor Debs (November 5, 1855 – October 20, 1926) was an American union leader, one of the founding members of the International Labor Union and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), and several times the candidate of the Social Democratic Party for President of the United States.[2] Through his presidential candidacies, as well as his work with labor movements, Debs eventually became one of the best-known socialists living in the United States. In the early part of his political career, Debs was a member of the Democratic Party of the United States. He was elected as a Democrat to the Indiana General Assembly in 1884. After working with several smaller unions, including the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen, Debs was instrumental in the founding of the American Railway Union (ARU), the nation's first industrial union. When the ARU struck the Pullman Palace Car Company over pay cuts, President Grover Cleveland used the United States Army to break the strike. As a leader of the ARU, Debs was later imprisoned for failing to obey an injunction against the strike. Debs educated himself about socialism in prison and emerged to launch his career as the nation's most prominent socialist in the first decades of the 20th century. He ran as the Socialist Party's candidate for the presidency in 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920, the last time from his prison cell. Noted for his oratory, it was a speech denouncing American participation in World War I that led to his second arrest in 1918. He was convicted under the Espionage Act of 1917 and sentenced to a term of 10 years. President Warren G. Harding commuted his sentence in December 1921. Debs died in 1926 not long after being admitted to a Sanatorium.

[edit] Early lifeEugene Debs was born on November 5, 1855, in Terre Haute, Indiana, to Jean Daniel and Marguerite Marie Bettrich Debs, who both immigrated to the United States from Colmar, Alsace, France. His father, who was born to a prosperous family in France, owned a textile mill and meat market. Eugene Victor Debs was named after the French authors Eugene Sue and Victor Hugo.[3] Debs dropped out of high school at age of 14 to work as a painter in railroad yards. In 1870, he became a boilerman. During his time as a boilerman, he attended a local business school during the night.[4] He returned home in 1874 to work as a grocery clerk. The next year he became a founding member and secretary of a new lodge of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen.[4] He rose quickly in the Brotherhood, becoming first an assistant editor for their magazine and then the editor and Grand Secretary in 1880. At the same time, he became a prominent figure in the community; in 1884 he was elected to the Indiana General Assembly as a Democrat, serving for one term.[4] The railroad brotherhoods were comparatively conservative unions, more focused on providing fellowship and services than in collective bargaining. Debs gradually became convinced of the need for a more unified and confrontational approach. After stepping down as Brotherhood Grand Secretary in 1893, he organized one of the first industrial unions in the United States, the American Railway Union (ARU). The Union successfully struck the Great Northern Railway in April 1894, winning most of its demands. Eugene Debs married Kate Metzel on June 9, 1885. The couple had no children.[4] Their home still stands in Terre Haute, within Indiana State University. [edit] Pullman StrikeSee also: Pullman Strike

Striking American Railway Union members confront Illinois National Guard troops in Chicago, Illinois, during Debs' Rebellion in 1894.

Debs became involved in the Pullman Strike in 1894, which grew out of a compensation dispute by the workers who constructed the train cars made by the Pullman Palace Car Company. The Pullman Company, due to falling revenue caused by the economic Panic of 1893, had cut the wages of its employees by 28%. The workers, many of whom were already members of the American Railway Union, appealed to the Union at its convention in Chicago, Illinois, for support.[2] Debs tried to persuade the Union members who worked on the railways that the boycott was too risky, given the hostility of both the railways and the federal government, the weakness of the Union, and the possibility that other unions would break the strike. The membership ignored his warnings and refused to handle Pullman cars or any other railroad cars attached to them, including cars containing U.S. Mail.[5] Debs finally decided to take part in the strike, which was endorsed by almost all members of the ARU in the immediate area of Chicago. Strikers fought by establishing boycotts of Pullman train cars, and with Debs' eventual leadership, the strike came to be known as "Debs' Rebellion".[3] The U.S. federal government intervened, obtaining an injunction against the strike on the theory that the strikers had obstructed the U.S. Mail, carried on Pullman cars, by refusing to show up for work. President Grover Cleveland sent the United States Army to enforce the injunction. The entrance of the Army was enough to break the strike; 13 strikers were killed, and thousands were blacklisted.[3] An estimated $80-million worth of property was damaged, and Debs was found guilty of contempt of court for violating the injunction and sent to federal prison.[3] Debs was represented by Clarence Darrow, hitherto a corporate lawyer for the railroad company, who "switched sides" to represent Debs. Darrow, a leading American lawyer and civil libertarian, had resigned his corporate position in order to represent Debs, making a substantial financial sacrifice in order to do so. A Supreme Court case decision, In re Debs, later upheld the right of the federal government to issue the injunction. [edit] Socialist leader

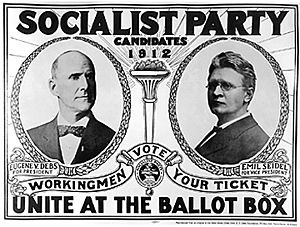

Campaign poster from his 1912 Presidential campaign, featuring Debs and Vice Presidential candidate Emil Seidel

At the time of his arrest for mail obstruction, Debs was not yet a socialist. While jailed in Woodstock, Illinois, he read the works of Karl Marx, whose ideological stances widely influenced socialism.[6] After Debs' release from prison in 1895, he started his Socialist political career. Already famous for his work as a union leader with the American Railway Union, Debs continued to gain popularity when he helped to found the Social Democracy of America. One year later this group split and Debs went with the majority faction to found the Socialist Democratic Party of the United States, also called the Social Democratic Party. Debs was elected chairman of the Executive Board of the National Council, the board which governed the party. Although the party did not have a sole figure that governed its actions, Debs' position as chairman and his notoriety gave him the status of party figurehead.[7] Debs' popularity with the party led to his nomination as a candidate for president of the United States in 1900 as a member of the Social Democratic Party. Along with his running mate Job Harriman, Debs received 87,945 votes–0.6% of the popular vote–and no electoral votes.[8] He was later the Socialist Party of America candidate for president in 1904, 1908, 1912, and 1920 (the final time from prison). In his showing in the 1904 election, Debs received 402,810 votes, which was 2.98% of the popular vote. Debs received no electoral votes, and, with vice presidential candidate Benjamin Hanford, ultimately finished third overall.[9] In the 1908 election, Debs again ran on the same ticket as Benjamin Hanford. While receiving a slightly higher number of votes in the popular vote, 420,852, he received 2.83% of the popular vote. Again Debs received no electoral votes.[10] Debs received 5.99% of the popular vote (a total of 901,551 votes) in 1912, while his total of 913,693 votes in the 1920 campaign remains the all-time high for a Socialist Party candidate.[11] Running alongside Emil Seidel, Debs again received no electoral votes.[12] Although he received some success as a third-party candidate, Debs was largely dismissive of the electoral process; he distrusted the political bargains that Victor Berger and other "Sewer Socialists" had made in winning local offices. He put much more value on organizing workers into unions, favoring unions that brought together all workers in a given industry over those organized by the craft skills workers practiced. Debs saw the working class as the one class to organize, educate, and emancipate itself by itself.[13] [edit] Founding the IWWAfter his work with the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and the American Railway Union, Debs' next major work in organizing a labor union came during the founding of the Industrial Workers of the World(IWW). On June 27, 1905, in Chicago, Illinois, Debs and other influential union leaders including Big Bill Haywood, leader of the Western Federation of Miners, and Daniel De Len, leader of the Socialist Labor Party, held what Haywood called the "Continental Congress of the working class". Haywood stated: "We are here to confederate the workers of this country into a working class movement that shall have for its purpose the emancipation of the working class...",[14] and for Debs: "We are here to perform a task so great that it appeals to our best thought, our united energies, and will enlist our most loyal support; a task in the presence of which weak men might falter and despair, but from which it is impossible to shrink without betraying the working class."[15] [edit] Socialists split with the IWWAlthough the IWW was built on the basis of uniting workers of industry, a rift began between the union and the Socialist Party. It started when the electoral wing of the Socialist Party, led by Victor Berger and Morris Hillquit, became irritated with speeches by Haywood.[16] In December 1911, Haywood told a Lower East Side audience at New York's Cooper Union that parliamentary Socialists were "step-at-a-time people whose every step is just a little shorter than the preceding step." It was better, Haywood said, to "elect the superintendent of some branch of industry, than to elect some congressman to the United States Congress."[17] In response, Hillquit attacked the IWW as "purely anarchistic..."[18] The Cooper Union speech was the beginning of a split between Bill Haywood and the Socialist Party, leading to the split between the factions of the IWW, one faction loyal to the Socialist Party, and the other to Haywood.[18] The rift presented a problem for Debs, who was influential in both the IWW and the Socialist Party. The final straw between Haywood and the Socialist Party came during the Lawrence textile strike when, disgusted with the decision of the elected officials in Lawrence, Massachusetts, to send police who subsequently used their clubs on children, Haywood publicly declared that "I will not vote again" until such a circumstance was rectified.[19] Haywood was purged from the National Executive Committee by passage of an amendment that focused on the direct action and sabotage tactics advocated by the IWW.[20] Debs was probably the only person who could have saved Haywood's seat.[21] In 1906, when Haywood had been on trial for his life in Idaho, Debs had described him as "the Lincoln of Labor" and called for Haywood to run against Theodore Roosevelt for president of the United States.[22], but times had changed and Debs, facing a split in the Party, chose to echo Hillquit's words, accusing the IWW of representing anarchy.[23] Debs thereafter stated that he had opposed the amendment, but that once it was adopted it should be obeyed.[24] Debs remained friendly to Haywood and the IWW after the expulsion, despite their perceived differences over IWW tactics.[23] Prior to Haywood's dismissal, the Socialist Party membership had reached an all-time high of 135,000. One year later, four months after Haywood was recalled, the membership dropped to 80,000. The reformists in the Socialist Party attributed the decline to the departure of the "Haywood element", and predicted that the party would recover. It did not; in the election of 1912 many of the Socialists who had been elected to public office lost their seats.[24] [edit] Leadership styleDebs was noted by many to be a charismatic speaker who sometimes called on the vocabulary of Christianity and much of the oratorical style of evangelism–even though he was generally disdainful of organized religion.[25] As Heywood Broun noted in his eulogy for Debs, quoting a fellow Socialist: "That old man with the burning eyes actually believes that there can be such a thing as the brotherhood of man. And that's not the funniest part of it. As long as he's around I believe it myself."[26] Although sometimes called "King Debs",[27] Debs himself was not wholly comfortable with his standing as a leader. As he told an audience in Utah in 1910:

[edit] Arrest and imprisonment

Debs' speeches against the Wilson administration and the war earned the undying enmity of President Woodrow Wilson, who later called Debs a "traitor to his country."[29] On June 16, 1918, Debs made a speech in Canton, Ohio, urging resistance to the military draft of World War I. He was arrested on June 30 and charged with 10 counts of sedition. His trial defense called no witnesses, asking instead that Debs be allowed to address the court in his defense. That unusual request was granted, and Debs spoke for 2 hours. He was found guilty on September 12. At his sentencing hearing on September 14, he again addressed the court, and his speech has become a classic. Heywood Broun, a liberal journalist and not a Debs partisan, said it was "one of the most beautiful and moving passage in the English language. He was for that one afternoon touched with inspiration. If anyone told me that tongues of fire danced upon his shoulders as he spoke, I would believe it."[30] He said in part:[31]

Debs was sentenced on November 18, 1918 to ten years in prison. He was also disenfranchised for life.[2] Debs presented what has been called his best-remembered statement at his sentencing hearing:

Debs appealed his conviction to the Supreme Court. In its ruling on Debs v. United States, the court examined several statements Debs had made regarding World War I and socialism. While Debs had carefully guarded his speeches in an attempt to comply with the Espionage Act, the Court found he still had the intention and effect of obstructing the draft and military recruitment. Among other things, the Court cited Debs' praise for those imprisoned for obstructing the draft. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. stated in his opinion that little attention was needed since Debs' case was essentially the same as that of Schenck v. United States, in which the Court had upheld a similar conviction.[33] Debs went to prison on April 13, 1919.[4] In protest of his jailing, Charles Ruthenberg led a parade of unionists, socialists, anarchists and communists to march on May 1 (May Day) 1919, in Cleveland, Ohio. The event quickly broke into the violent May Day Riots of 1919. Debs ran for president in the 1920 election while in prison in Atlanta, Georgia, at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary. He received 913,664 write-in votes (3.4%),[34] slightly less than he had won in 1912, when he received 6%, the highest number of votes for a Socialist Party presidential candidate in the U.S.[4][35] His time in prison also inspired Debs to write a series of columns deeply critical of the prison system, which appeared in sanitized form in the Bell Syndicate and appeared in his only book, Walls and Bars, with several added chapters. It was published posthumously.[2] In March 1919 President Wilson asked Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer for his opinion on clemency for Debs, but offered his own: "I doubt the wisdom and public effect of such an action." Palmer generally favored releasing people convicted under the wartime security acts, but when he consulted with Debs' prosecutors–even those with records as defenders of civil liberties–assured him that Debs' conviction was correct and his sentence appropriate.[36] The President and his Attorney General both believed that public opinion opposed clemency and that releasing Debs could strengthen Wilson's opponents in the debate over the ratification of the peace treaty. Palmer proposed clemency in August and October 1920 without success.[37] At one point Wilson wrote: "While the flower of American youth was pouring out its blood to vindicate the cause of civilization, this man, Debs, stood behind the lines sniping, attacking, and denouncing them....This man was a traitor to his country and he will never be pardoned during my administration."[38] In January 1921, Palmer, citing Debs' deteriorating health, proposed to President Wilson that Debs receive a presidential pardon freeing him on February 12, Lincoln's birthday. President Wilson returned the paperwork after writing "Denied" across it.[39] On December 23, 1921, President Harding commuted Debs' sentence to time served, effective Christmas Day. He did not issue a pardon. A White House statement summarized the administration's view of Debs' case: "There is no question of his guilt....He was by no means as rabid and outspoken in his expressions as many others, and but for his prominence and the resulting far-reaching effect of his words, very probably might not have received the sentence he did. He is an old man, not strong physically. He is a man of much personal charm and impressive personality, which qualifications make him a dangerous man calculated to mislead the unthinking and affording excuse for those with criminal intent."[40] [edit] Last yearsWhen Debs was released from the Atlanta Penitentiary, the other prisoners sent him off with "a roar of cheers" and a crowd of 50,000 greeted his return to Terre Haute to the accompaniment of band music.[41] En route home, Debs was warmly received at the White House by Harding, who greeted him by saying: "Well, I've heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now glad to meet you personally."[42] In 1924, Debs was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the Finnish Socialist Karl H. Wiik on the grounds that "Debs started to work actively for peace during World War I, mainly because he considered the war to be in the interest of capitalism."[43] In the fall of 1926, Debs was admitted to a sanitarium in Elmhurst, Illinois.[2] He died there on October 20, 1926, at the age of 70.[2][41] [edit] LegacyEugene Debs helped motivate the American Left as a measure of political opposition to corporations and World War I. American socialists, communists, and anarchists honor his compassion for the labor movement and motivation to have the average working man build socialism without large state involvement.[44] Several books have been written about his life as an inspirational American socialist.[45] On May 22, 1962, Debs' home was purchased by the Eugene V. Debs Foundation for $9,500 and the work of making it into a Debs memorial was begun. In 1965 it was made an official historic site of the state of Indiana, and in 1966 it was made an official National Historic Landmark of the National Parks system of the Department of Interior of the United States. The preservation of the museum is monitored regularly by the National Park Service.[46] In 1990, the U.S. Department of Labor named Debs a member of its Labor Hall of Fame.[47] [edit] Works

[edit] References

[edit] Sources

[edit] External links

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL). |

Connect with Connexions

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||