Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Arab Revolt

|

|||||||||

| Arabia and Southern Arabia Campaigns | |

|---|---|

| Part of Middle Eastern theatre of World War I | |

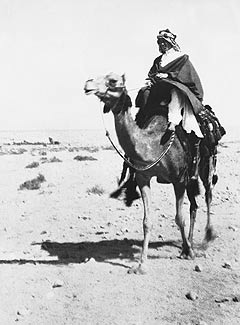

Lawrence of Arabia after the Battle of Aqaba. |

|

This article is about the Arab Revolt of 1916. For the 1936 revolt, see 1936 - 1939 Arab revolt in Palestine.

The Arab Revolt (1916 - 1918) was initiated by the Sherif Hussein bin Ali with the aim of securing independence from the ruling Ottoman Turks and creating a single unified Arab state spanning from Aleppo in Syria to Aden in Yemen.

Contents |

Further information: Second Constitutional Era (Ottoman Empire)

The rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire goes back to 1821. Arab nationalism has its roots in the Mashriq (the Arabs lands east of Egypt), particularly in countries of Sham (the Levant). The political orientation of Arab nationalists in the years prior to the Great War was generally moderate.

The Young Turk Revolution began on 3 July 1908 and quickly spread throughout the empire, resulting in the sultan's announcement of the restoration of the 1876 constitution and the reconvening of parliament. This period is known as the Second Constitutional Era. The Arabs' demands were of a reformist nature, limited in general to autonomy, greater use of Arabic in education, and changes in conscription in the Ottoman Empire in peacetime for Arab conscripts that allowed local service in the Ottoman army. In the elections held in 1908, the Young Turks through their Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) managed to gain the upper hand against the rival group led by Prince Sabahaddin. The CUP was more liberal in outlook, bore a strong British imprint, and was closer to the Sultan. The new parliament comprised 142 Turks, 60 Arabs, 25 Albanians, 23 Greeks, 12 Armenians (including four Dashnaks and two Hunchas), 5 Jews, 4 Bulgarians, 3 Serbs, and 1 Vlach. The CUP in the Ottoman parliament gave more emphasis to centralization and a modernization programme. At this stage Arab nationalism was not yet a mass movement, even in Syria where it was strongest. Many Arabs gave their primary loyalty to their religion or sect, their tribe, or their own particular governments. The ideologies of Ottomanism and Pan-Islamism were strong competitors of Arab nationalism.

Arab members of the parliament supported the Countercoup (1909), which aimed to dismantle the constitution and restore the monarchy of Abdul Hamid II. The dethroned Sultan attempted to regain the Caliphate by putting an end to the secular policies of the Young Turks, but was in turn driven away to exile in Selanik by the 31 March Incident and was eventually replaced by his brother Mehmed V ReÅad.

In 1913, intellectuals and politicians from the Arab Mashreq met in Paris at the first Arab Congress. They produced a set of demands for greater autonomy within the Ottoman Empire. They again demanded that Arab conscripts to the Ottoman army should not be required to serve in other regions except in time of war.

It is estimated that the Arab forces involved in the revolt numbered around 5,000 soldiers. This number however probably applies to the Arab Regulars who fought with Allenby's main army, and not the irregular forces under the direction of Lawrence and Feisal. On a few occasions, particularly during the final campaign into Syria, this number would grow significantly. Many Arabs joined the Revolt sporadically, often as a campaign was in progress or only when the fighting entered their home region. During the Aqaba raid, for instance, while the initial Arab force numbered only a few hundred, over a thousand more from local tribes joined them for the final assault on Aqaba. Estimates of Hussein's effective forces vary, but through most of 1918 at least, they may have numbered as high as 30,000 men.

It should also be noted that in the early days of the Revolt, Hussein's forces were largely made up of Bedouin and other nomadic desert tribes, who were only loosely allied, loyal more to their respective tribes than the overall cause. Feisal had hoped that he could convince Arab troops serving in the Turkish army to mutiny and join his cause; but the Turkish government sent most of its Arab troops to the front-lines of the war, and thus only a handful of deserters actually joined the Arab forces until later in the campaign.

The main contribution of the Arab Revolt to the war was to pin down tens of thousands of Turkish troops who otherwise might have been used to attack the Suez Canal, allowing the British to undertake offensive operations with a lower risk of counter-attack. This was indeed the British justification for starting the revolt, a textbook example of asymmetrical warfare which has been studied time and again by military leaders and historians alike.

Further information: Middle Eastern theatre of World War I

The Ottoman Empire took part in the Middle Eastern theatre of World War I, under the terms of the Ottoman-German Alliance. Many Arab nationalist figures in Damascus and Beirut were arrested, then tortured. The flag of the resistance was designed by Sir Mark Sykes, in an effort to create a feeling of "Arab-ness" in order to fuel the revolt.[1]

Because of repression by the Turks and their Central Powers allies, Grand Sharif Hussein, as the head of the Arab nationalists, entered into an alliance with the United Kingdom and France against the Ottomans sometime around 8 June 1916, the actual date being somewhat uncertain. This alliance was facilitated by the services of a mysterious young Arab officer in the Ottoman army named Muhammed Sharif al-Faruqi.[2]

Hussein had about 50,000 men under arms, but fewer than 10,000 had rifles.[3] Evidence that the Ottoman government was planning to depose him at the end of the war led him to an exchange of letters with British High Commissioner Henry McMahon which convinced him that his assistance on the side of the Triple Entente would be rewarded by an Arab empire encompassing the entire span between Egypt and Persia, with the exception of imperial possessions and interests in Kuwait, Aden, and the Syrian coast. French and British naval forces had cleared the Red Sea of Ottoman gunboats early in the war.[4] The port of Jidda was attacked by 3500 Arabs on 10 June 1916 with the assistance of bombardment by British warships and seaplanes.[3] The Ottoman garrison surrendered on 16 June.[3] By the end of September 1916 Arab armies had taken the coastal cities of Rabegh, Yenbo, Qunfida, and 6000 Ottoman prisoners with the assistance of the Royal Navy.[3] Fifteen thousand well-armed Ottoman troops remained in the Hejaz.[3] However, a direct attack on Medina in October resulted in a bloody repulse of the Arab forces.

The British government in Egypt sent a young officer, Captain T. E. Lawrence, to work with the Arabs in October 1916.[4] Lawrence obtained assistance from the Royal Navy to turn back an Ottoman attack on Yenbo in December 1916.[5] Lawrence's major contribution to the revolt was convincing the Arab leaders (Faisal and Abdullah) to co-ordinate their actions in support of British strategy. He persuaded the Arabs not to drive the Ottomans out of Medina; instead, the Arabs attacked the Hejaz railway on many occasions. This tied up more Ottoman troops, who were forced to protect the railway and repair the constant damage.

The coastal city of Wejh was to be the base for attacks on the Hejaz railway.[5] On 3 January 1917, Faisal began an advance northward along the Red Sea coast with 5100 camel riders, 5300 men on foot, four Krupp mountain guns, ten machine guns, and 380 baggage camels.[5] The Royal Navy resupplied Faisal from the sea during his march on Wejh.[6] While the 800-man Ottoman garrison prepared for an attack from the south, a landing party of 400 Arabs and 200 Royal Navy bluejackets attacked Wejh from the north on 23 January 1917.[6] Wejh surrendered within 36 hours, and the Ottomans abandoned their advance toward Mecca in favor of a defensive position in Medina with small detachments scattered along the Hejaz railway.[7] The Arab force had increased to about seventy-thousand men armed with twenty-eight-thousand rifles and deployed in three main groups.[7] Ali's force threatened Medina, Abdullah operated from Wadi Ais harassing Ottoman communications and capturing their supplies, and Faisal based his force at Wejh.[7] Camel-mounted Arab raiding parties had an effective radius of 1000 miles (1600 km) carrying their own food and taking water from a system of wells approximately 100 miles (160 km) apart.[8]

In 1917, Lawrence arranged a joint action with the Arab irregulars and forces under Auda Abu Tayi (until then in the employ of the Ottomans) against the port city of Aqaba. This is now known as the Battle of Aqaba. Aqaba was the only remaining Ottoman port on the Red Sea and threatened the right flank of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force defending Egypt and preparing to advance into Palestine.[8] Capture of Aqaba would aid transfer of British supplies to the Arab revolt.[9] Lawrence and Auda left Wedj on 9 May 1917 with a party of 40 men to recruit a mobile camel force from the Howeitat of Syria.[9] On 6 July, after an overland attack, Aqaba fell to those Arab forces with only a handful casualties.[9] Lawrence then rode 150 miles to Suez to arrange Royal Navy delivery of food and supplies for the 2500 Arabs and 700 Ottoman prisoners in Aqaba; soon the city was co-occupied by a large Anglo-French flotilla (including warships and sea planes), which helped the Arabs secure their hold on Aqaba.[9] Later in the year, the Arab warriors made small raids on Ottoman positions in support of General Allenby's winter attack on the Gaza-Bersheeba defensive line (see the Battle of Beersheba).[10] Allenby's victories led directly to the capture of Jerusalem just before Christmas 1917.

By the time of Aqaba's capture, many other officers joined Feisal's campaign. A large number of British officers and advisors, led by Lt. Col.s Stewart F. Newcombe and Cyril E. Wilson, arrived to provide the Arabs rifles, explosives, mortars, and machine guns. Artillery was only sporadically supplied due to a general shortage, though Feisal would have several batteries of mountain guns (under French Captain Pisani) for the Megiddo Campaign. Egyptian and Indian troops also served with the Revolt, primarily as machine gunners and specialist troops, a number of armored cars were allocated for use, the Royal Flying Corps often supported the Arab operations, and the mostly-Australian Imperial Camel Brigade served with the Arabs for a time. A small contingent of French soldiers also joined the Arabs, although their relationship with the Arabs was generally antagonistic, due to France's loudly-proclaimed imperial ambitions in Syria.

Under the direction of Lawrence, Wilson, and other officers, the Arabs launched a highly successful campaign against the Hejaz Railway, capturing military supplies, destroying trains and tracks, and tying down thousands of Turkish troops. Though the attacks were mixed in success, they achieved their primary goal of tying down Turkish troops and cutting off Medina. In February 1918, in one of the largest set-piece battles of the Revolt, Arab forces (including Lawrence) defeated a large Turkish force at the village of Tafileh, inflicting over 1,000 Turkish casualties for the loss of a mere forty men.

In 1918, the Arab cavalry gained in strength (as it seemed victory was at hand) and they were able to provide Allenby's army with intelligence on Ottoman army positions. They also harassed Ottoman supply columns, attacked small garrisons, and destroyed railroad tracks. A major victory occurred on 27 September when an entire brigade of Turkish and German troops, retreating from Mezerib, was virtually wiped out in a battle with Arab forces near the village of Tafas (which the Turks had plundered during their retreat). In part due to these attacks, Allenby's last offensive, the Battle of Megiddo (1918), was a stunning success. The Ottoman army was routed in less than 10 days of battle. Allenby praised Feisal for his role in the victory: "I send your Highness my greetings and my most cordial congratulations upon the great achievement of your gallant troops... Thanks to our combined efforts, the Turkish army is everywhere in full retreat".[11]

The first Arab Revolt forces to reach Damascus were Sharif Naser's Hashemite camel cavalry and the cavalry of the Ruwallah tribe, led by Nuri Sha'lan, on 30 September 1918. The bulk of these troops remained outside of the city with the intention of awaiting the arrival of Sharif Feisal. However, a small contingent from the group was sent within the walls of the city, where they found the Arab Revolt flag already raised by surviving Arab nationalists among the citizenry. Later that day Australian Light Horse troops marched into Damascus. Auda Abu Ta'yi, T. E. Lawrence and Arab troops rode into Damascus the next day, 1 October. At the end of the war, the Egyptian Expeditionary Force had seized Palestine, Transjordan, Lebanon, large parts of the Arabian peninsula and southern Syria. Medina, cut off from the rest of the Ottoman Empire, would not surrender until January 1919.

See also: Partitioning of the Ottoman Empire

The United Kingdom agreed in the Hussein-McMahon Correspondence that it would support Arab independence if they revolted against the Ottomans. The two sides had different interpretations of this agreement. In the event, the United Kingdom and France reneged on the original deal and divided up the area in ways unfavourable to the Arabs under the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement. Further confusing the issue was the Balfour Declaration of 1917, which promised support for a Jewish "national home" in Palestine. The Hedjaz region of western Arabia became an independent state under Hussein's control, until 1927, when, abandoned and isolated by the British policy - which had shifted support to the al Saud family - it was conquered by Saudi Arabia, ending an era of over 600 years of Hashemite stewardship of the holy land of Islam.

|

|

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions