Three

The East York

Workers'

Association

In March of 1931 200

people met in a local school to discuss solutions to the

unemployment problem. The newspaper account does not name the

meeting's sponsors but the speakers were the reeve, R. M. Leslie,

the local Conservative M.P., R. H. McGregor and two councillors,

John Hollinger, who owned the local bus line, and Joe Vernon.

Clearly unemployment was not a matter of concern only to the

unemployed or the radicals; the more conservative element in the

community was also alarmed.

The East York Workers'

Association was founded in June.

No account has been located of the initial meeting. One early

participant in the East York Workers Nell Binns, suggests that "It

was through people — men especially -meeting at the welfare office

to pick up their welfare vouchers that the idea of the East York

Workers started."

It may have been this spontaneous an occurrence, although the fact

that the first president of the organization, James Sutherton, was a

socialist,

as was another founding member, Alex Lyon,

would seem to indicate a more conscious intervention by socialists.

Throughout the depression the organized trade union movement and all

the radical socialist and communist groups tried in various ways to

organize the unemployed or to intervene in already existing

organizations One early activist in the East York Workers' Bert

Hunt, describes Sutherton's activities this way.

I

heard of Jim Sutherton; he advertised in the personal column in the

Star for interested people to meet him and join a socialist party.

I don't know if he got any applications or not. I telephoned him and

he told me he'd let me know when he could call a meeting, but it

never happened. Then one Tuesday night... I went to the regular

meeting of the unemployed and it was well organized. Sutherton was

in control. They had a secretary, a financial secretary and a

treasurer and charged 5¢ to join and 5¢ a month.

Another early participant

in the movement, Frank Kenwell, recalls that it developed from a

Ratepayers Association in which Sutherton was involved.

(Sutherton was president of the Woodbine Greenwood Ratepayers

Association and secretary of the Central Council of Ratepayers; so

Kenwell is probably correct.)

The East York Workers' Association then, was formed from existing

organizations and public meetings, bolstered by the day to day

contacts of relief recipients in the welfare office and aided by the

intervention of socialists like Sutherton. By 1934 the E.Y.W.A. had

signed up 1,600 members.

Four to five hundred people attended weekly meetings at a local

school.

With plenty of leisure and no money to spend on recreation, the

meetings not only organized the participants into a defensive

organization that could fight for higher relief and better living

conditions, but also provided an educational and social experience.

Nell Binns recalls them as

"mostly discussions amongst ourselves — which was good — it was

tremendous really for people to let go to people who understood."

At one meeting in 1933, chaired by Mrs. Elizabeth Morton, items of

social and township interest were discussed. Mrs. H. Haines of the

Women's Study Group gave a talk on Marxism. Bert Hunt from the Young

Men's Study Class spoke on "Why should the producers of the world's

wealth be starving?" and an announcement was made of an eviction to

be blocked. Then Mrs. Good sang to close this meeting of 800 people.

They also held debates on current affairs sometimes with

Conservatives or Liberals taking one side of the argument and

socialists the other.

Occasionally they had

visiting speakers. Premier Henry, who represented East York

provincially, spoke at one of their first meetings. At later ones

they heard Salem Bland, (a leading exponent of the social gospel),

J. S. Woodsworth, Angus MacInnis, Frank Underhill, and Agnes Macphail

(all of the CCF), Thomas Crudon, (chairman of the Ontario Socialist

Party), Jack McDonald (a founder of the Communist Party who had been

expelled for Trotskyism), and J. L. Cohen (a Communist Party lawyer

who also helped them with legal problems).

Bert Hunt describes the

Woodsworth-MacInnis meeting.

We got in contact with Woodsworth's secretary in Toronto on

Grenadier Road and we offered to organize a mass meeting if Mr.

Woodsworth would speak. He agreed and we plastered the township with

signs. When Mr. Woodsworth came to Toronto after we had told

everyone in the township and in the city too, that we were having

him, we got a phone call telling us that he would be unable to

attend. We got busy — we rushed to Grenadier Road and we really laid

down the law — described what we'd done — we told them we'd have a

mob — and finally Mr. Woodsworth agreed that he'd have to cancel his

other appointments and come. We filled both the Danforth Park Public

School auditorium and the McGregor School auditorium to overflowing

and had a speaker outside the meetings. We had his son-in-law, Grace

MacInnis's husband — in one meeting and Woodsworth at the other. Now

I can't remember, they might have switched schools — it wouldn't

take long — and make an appearance at both — I imagine they did. But

after the meeting the local committee met in Johnny Walker's home —

the biggest home of anybody sympathetic to us — until 2 or 3 o'clock

in the morning discussing the CCF and Jimmy Woodsworth and Angus

MacInnis.

Within the organization

various groups developed including a Young Men's and a Women's Study

Group.

The latter, composed of about eight women met one afternoon a week

to study Marxism. Each woman would do some reading at home and then

they would hold a discussion at the meeting. Occasionally they would

have an outside speaker but that was not the usual procedure.

The Women's Group organized a library, an important matter in a

group that was rapidly evolving politically and whose members had

plenty of leisure to read.

They also carried most of the money raising activities, but when on

one occasion, the men decided how much money was needed, how to

raise it, and how to spend it and then left the work to the women,

they were called to order.

Women were frequently candidates and spokespersons for the group

although less often then men. It was a women's deputation however

that presented council with a demand for birth control supplies on

the relief allotment. They solved their baby-sitting problems by

leaving their children with a grandmother or neighbour or they

brought them to the activities. They sold CCF literature and

publications from the American socialist publisher, Charles Kerr.

Many of the group's

activities were social. They held dances (advertised in the New

Commonwealth) and card parties (when they could find someone who

still had a deck of cards). Nell Binns talked about the East York

Workers football team.

The East York Workers formed a football team. My husband was

secretary, coach and trouble shooter — he didn't play but he was

instrumental in seeing that the team functioned alright. He managed,

I don't know how, but he managed to get another football team's cast

off uniforms and we had a big tin box like one of the very old

travelling trunks and we used to keep the uniforms in this box in

our basement. After every game my husband and I would wash them and

I would mend the socks and everything and we would hang them out on

the clothesline. Then on Saturday when the men were going out to a

game they would all gather and sit on our lawn until they were all

there and a truck would come, they all chipped in for a truck to

take them where they were going with the uniforms. We had a

neighbour across the road who was a bit on the nosy side and she

reported my husband and me to the welfare department. There were all

these young men meeting on our lawn and us carrying out this tin

trunk — we must be making beer and selling it. We really got into

trouble about it — it's comical now but at the time it was a bit

tragic.

The group reflected the

ethnic composition of the township; all the names in the accounts

are Anglo-Saxon although one Italian family, the Buccinos, did

participate in the group.

One of the major problems

confronting the group was that of developing spokespersons and

candidates. They had a particular problem finding a president since

few of their members were articulate enough to perform that

function. Bert Hunt describes the succession of presidents:

(Jim Sutherton was) a very right-wing labourite, a British

labourite. A pleasant Sunday afternoon, Sunday school type. Looking

back at it, you know. But he was working in a territory where he was

too advanced for the members even. To my way of looking at things,

then he was the right man for the job ... well Jim Sutherton took

sick. He had a tumour on the brain — we didn't know it at the time

of course. We wondered why he was acting a little queer. On one

occasion, Bob McGregor (the local Conservative MP) got on the

platform and claimed that he had his pockets full of papers to prove

that Sutherton was sent in here from Moscow. Poor old Sutherton

nearly went mad. The next thing we heard he was in Winnipeg and then

we found out much later that he had died from a tumour on the brain.

Bill Walker was the vice-president and Bill had been a very

enthusiastic labourite all his life and he had a good appearance but

he had no command of the English language at all — he was

semi-illiterate. He could just read and that was all. Bill took over

the leadership but everybody felt let down quite a bit. Then he gave

it up and a guy named Frechette took over. Frechette punched a

welfare officer in the jaw — he was demanding coal — and he told the

welfare officer you give coal according to the temperature not the

calendar and I think he did a week in jail. Anyway we had to get him

out of there because it was beginning to be too difficult. Bill

Walker went back in and he was floundering. We had noticed some tall

individual standing at the back of the hall never speaking — he must

have been at quite a few meetings. All of a sudden he makes a five

minute speech — perfectly fluent English — an eloquent elocutionist.

It happened to be an election night and he was elected to the audit

committee. When he gave the audit report at the next meeting it was

perfect. His speech was marvellous and he was immediately elected

president. Nobody knew him from a load of hay.

The new president was

Arthur Williams and his account of his election was confirmed by

Sarah McKenzie. "He just seemed to come up out of the ground as it

were — nobody had heard of him until the next thing we knew he was

nominated and chairman."

The problem of course with this situation is that the man was

elected not because his views were necessarily in agreement with

those of the majority of the group (although Williams did state in

his acceptance speech that he was a socialist),

but simply because he spoke well. Their lack of formal education and

experience in public office was a serious handicap when these

workers attempted to organize themselves.

"From then on Williams was

the East York Workers. He dominated them and controlled them."

He was elected in June 1933, by which time the organization was well

organized and very active.

Its main business, of course, was the never ending struggle for

food, clothing, and shelter. Frequently confrontations with the

relief administrators took place on an individual basis. Sarah

McKenzie recalls living in a draughty badly built house on Gledhill

Avenue which took an enormous amount of fuel to heat. Her husband

tried to get more fuel from the relief officials and was turned

down. He went home, got his wife and child, and returned to the

relief office because it at least was heated. Their child was a very

curious toddler and they let her run about the office investigating

it thoroughly for several hours. The relief workers then changed

their minds and gave the McKenzies the fuel.

Nell Binns recounts that

on one occasion their furnace had broken down completely beyond

repair.

So Billy went over to the welfare office and told them and they

couldn't do anything about it. So he went down to Queen's Park and

they gave him an order to go to a place on Broadview where they sold

second hand furnaces. He got one there and it was $26.00 for the

whole works. He got it home and he didn't have any tools to install

it so that whole furnace was installed with a can opener. The funny

part of it was that after he installed it and lit the fire three men

came from the East York Welfare Office to say we couldn't have the

furnace because they hadn't OK'd it. Queen's Park wasn't good enough

for them. But the furnace was lit and so they couldn't take it away.

Olive Hill (formerly Olive

Deloge) recounts that when she applied for some medical assistance

from the Department of Health, the visiting health officer asked her

when her husband would be home. "You see, I use to have a French

Canadian name and he said to me 'you know, I'm just dying to get

together with a French woman.' He was an old drunk."

Sometimes what began as an

individual fight was taken up by the group. Nell Binns recounts this

incident.

He had four quite young children and they all caught measles at the

same time. They had a small radio that he had built himself and the

children were sick and shut in and this radio was all they had to

amuse them. A tube broke and he went to the welfare office and

explained the situation to them. He thought a radio tube or the cost

of a radio tube was very essential to him. Well he was laughed at by

the welfare officials, and told that he would just have to stay home

and amuse them, read to them and play with them. Fortunately he

wasn't satisfied with that answer and took it to the council and he

was turned down there and he approached his MPP and he was turned

down there. But then a delegation from the East York Workers went to

the welfare board and said they agreed that he needed the radio tube

and they would be quite willing to chip in a nickel a piece out of

their very meagre relief allowance but they would let the newspapers

know about it, and in that way the welfare came across with the

money.

There were endless

deputations to the township council complaining that the heating

allowance was inadequate,

that hydro was being cut off to relief recipients in arrears on

their bills,

that the clothing depot would give each person only one suit of

underwear,

that the only dental treatment allowed relief recipients was

extractions,

and that the relief investigator had rotten manners.

The main demand, however, was simply for more money and members of

the township council became expert at dodging the deputations as did

the East York Workers in pressing their demands:

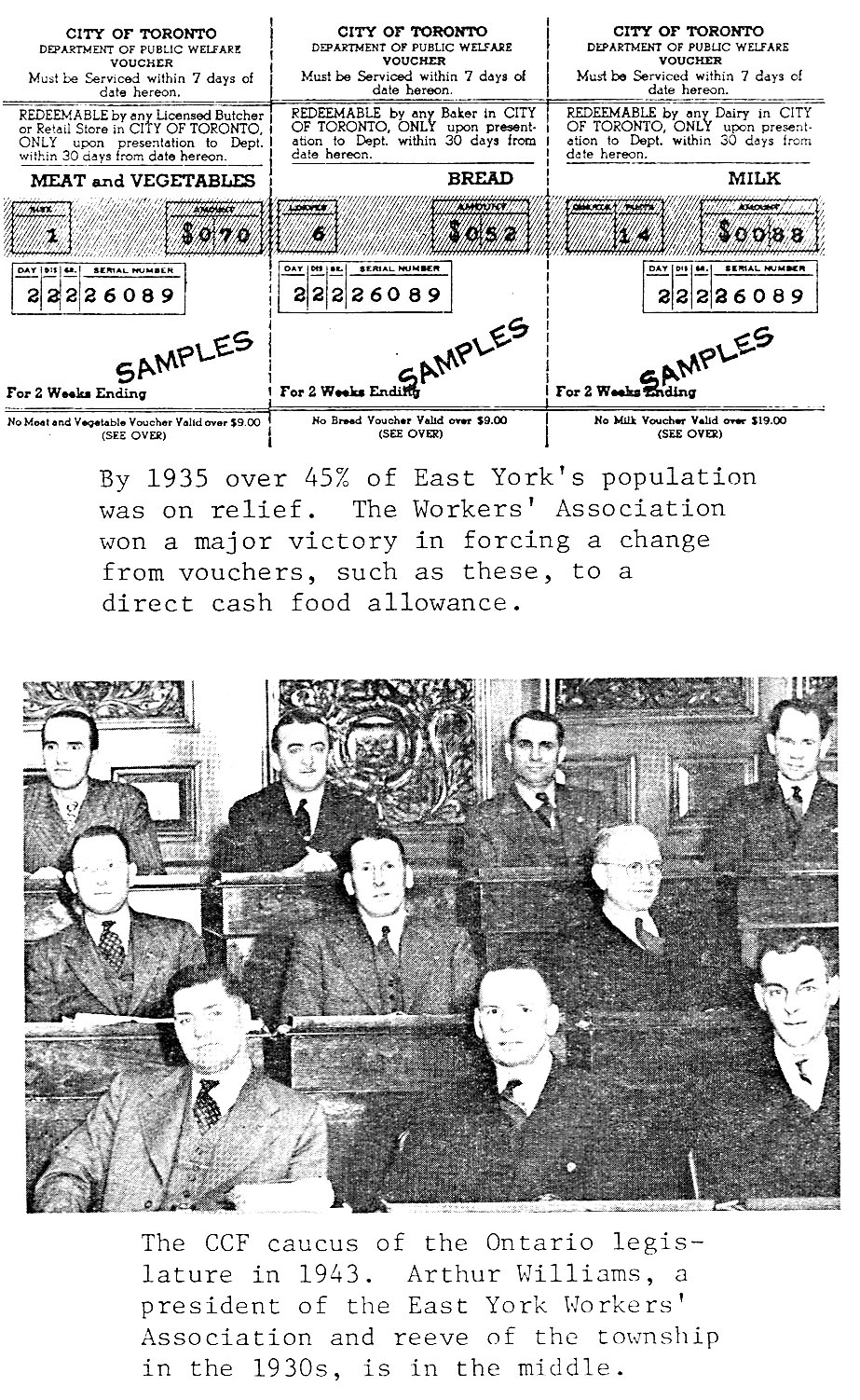

...We wanted cash instead of vouchers and the councillors made a

date to see a delegation. We never trusted them very much so the

delegation went but just about all of the East York Workers were

hiding around corners or sitting in trucks or somebody's house close

by. The council just didn't turn up at all so we all went in the

municipal office and we sat. We had taken a sandwich with us. Mr.

Murphy ... played a concertina and we spent the entire day there and

we danced and he played his concertina and we sang and we stayed

there, until finally some of the councillors had to come. That was

the time we got the voucher changed into cash.

The method of payment of

relief was the subject of endless controversy. The voucher system

restricted recipients to purchases from specific stores and

sometimes they could not be used in chain stores where prices were

lowest. Some local merchants would illegally exchange the vouchers

for cash at a discount and Williams cited the case of a policeman

who was given $1.30 cash for an open voucher of $2.15.

One shoe repairer was

charged with cashing vouchers and with using linoleum to repair

shoes although he was paid for leather. He supposedly received

$4,000 in four months.

According to Binns,

"Anyone who needed glasses was sent to this one store on the

Danforth and the man, finally, after a few years, was arrested. He

was putting just plain window glass in frames."

Another example of problems with the voucher system was indicated by

a Sammon Avenue grocer:

People come in here, for example and want to take olives or sardines

or fancy things on which there might be more profit for me. I won't

allow them to do it although I would have a lot more relief voucher

trade if I did. I make them take sensible things that they really

need.

The vouchers did not

specify precisely which food items might be purchased but the more

affluent members of the community, like this store-owner, seemed to

feel they had every right to intervene in the spending of the relief

recipients' meagre allowance.

Switching from vouchers to

cash solved these problems and it was regarded as an enormous

victory for the Association.

Township officials granted

some of the demands of the East York Workers partly because they

were sympathetic to their problems and partly because they were

afraid of them. Early in 1931 Deputy Reeve Harry Meighen expressed

these feelings in a speech to the York County Council:

When the home is gone and children starving their spirit

changes...In Leaside and East York there are unemployed billetted in

caves (referring to the men living in unused brick kilns on the Don

Flats) ...(and) a meeting of unemployed was held in East York last

night attended by 250 and if an agitator came among them anything

might happen.

He worried that many of

the men were militia members and consequently had guns at home.

But relief policies were not determined solely by the township

council. Provincial government decisions were crucial in the

situation.