|

|

|

|

NEWS & LETTERS, May-June 2012

Woman as Reason

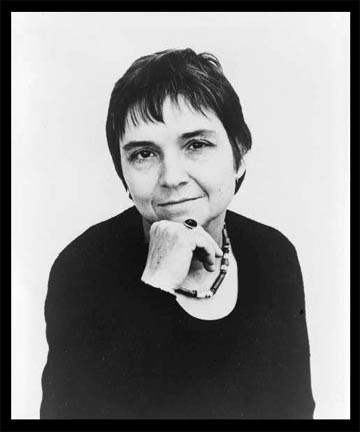

Adrienne Rich--a voice for freedom

by Olga Domanski

The world lost a passionate, beautiful voice for freedom and self-determination with the death of the feminist Lesbian poet Adrienne Rich on March 27. Whether it be the precision of her poetry or essays, what is always inescapable is that Rich not only spoke for herself, but articulated the desire of legions for a different, a profoundly human existence.

Rich's death took me back to the letter I received from her the week Raya Dunayevskaya, whose secretary I had been, died unexpectedly in 1987: "I have been thinking about all of you who were her close co-workers and had the privilege of knowing her as a person. I had been hoping to meet her. I feel keenly the loss of that opportunity. But how much she left behind, for all of us to draw on and pursue in our several ways!"

A SPECIAL RELATIONSHIP

The special relationship between them had begun in 1986, when Rich--at the urging of her friend, the African-American feminist scholar Gloria Joseph--read through all of Dunayevskaya's major works, and was impelled to review them for the September 1986 Women's Review of Books. She called her review "Living the Revolution," and News & Letters printed excerpts in the November 1986 issue to continue the discussion.

Her review ended by accepting Dunayevskaya's challenge to "commit ourselves to a more inclusive definition of freedom than has ever been attempted" by "leaping forward from Marx who had been moving in that direction." Dunayevskaya responded in the December 1986 issue, explaining that she was embarking on a new work on Dialectics of Organization and Philosophy.

Their relationship came to an abrupt halt with Dunayevskaya's death in 1987. In 1990, however, Rich decided to write the foreword for a new edition of Rosa Luxemburg, Women's Liberation, and Marx's Philosophy of Revolution because, as she wrote, "In the last couple of weeks I have begun to see more clearly the dimension of my own book and Raya’s presence in it, and to feel that in writing the introduction I could also enrich my own project--in short, that there would be more continuity than interruption involved….[I]t is Raya’s voice which speaks, in these days, with even greater urgency and clarity than when I first began to study her work."

THE FULLNESS OF BEING HUMAN

Rich's foreword ends: "It's made so difficult, under the prevailing conditions of capital-shaped priorities, male supremacism, racism, militarism to envision that revolution without end to which Dunayevskaya devoted her life…we can lose sight of the fact that we 'live human beings' are where it all must begin….Raya Dunayevskaya never let go of her experiences of the fullness of being human--and she wanted that to be the normal experience of every human being, everywhere." That is the vision that Adrienne Rich kept alive throughout her own life.

Her appreciation for what Dunayevskaya had created as the philosophy of Marxist-Humanism changed her life. She marked the precise point in Blood, Bread, and Poetry (1986). She noted that in 1975 she had written: "Much of what is termed 'politics' seems to rest on a longing for certainty even at the cost of honesty, for an analysis which, once given, need not be reexamined. Such is the deadendedness--for women--of Marxism for our time." At that point Rich added a footnote (although some copies had already been published). She dated it carefully: "A.R. 1986. For a vigorous indictment of dead-ended Marxism and a call to 'revolution in permanence,' see Raya Dunayevskaya, Women's Liberation and the Dialectics of Revolution."

Several unique characteristics become evident in this action. One is the precision with which she sought to mark this moment; another is the question of what "honesty" meant to her, which becomes clear in her constant return to this moment. The need was for honesty to herself, first and foremost.

THE RELATION OF ART TO JUSTICE

That honesty was displayed in a different way in her refusal to accept the National Medal for the Arts in 1997, when she famously informed Jane Alexander that while "there is no simple formula for the relationship of art to justice....I do know that art, in my own case, the art of poetry, means nothing if it simply decorates the dinner table of power that holds it hostage."

The moment Rich had documented in 1986 when she grasped the life-changing meaning of Raya Dunayevskaya's philosophy of Marxist-Humanism, was demonstrated in all her work thereafter but explicitly expressed in two of her prose collections. In What Is Found There, published in 1993, the penultimate chapter of the 28 essays sums up what she saw herself as responsible for demonstrating. She wrote: "Raya Dunayevskaya wrote of revolution that while 'great divides in epochs, in cognition, in personality, are crucial,' we need to understand the moment of discontinuity--the break in the pattern--itself as part of a continuity, for it to become a turning point in human history." She concluded, "Poetry is not a resting on the given, but a questing toward what might otherwise be."

In her 2001 collection, Arts of the Possible, the first four essays show the inability to fulfill her direction "within feminism alone." The rest of the collection begins with the reprinting of her foreword to the 1991 edition of Dunayevskaya's book on Rosa Luxemburg. She calls the chapter simply "Raya Dunayevskaya's Marx."

Adrienne Rich found in Dunayevskaya's work what she had passionately been looking for. It becomes a challenge to all those struggling for a new world on human foundations--especially those who carry the revolutionary banner of "women's liberation" today.

We deeply mourn Adrienne Rich's death, and greatly honor her life.

|

Women's Liberation and the Dialectics of Revolution: Reaching for the Future

A 35-Year Collection of Essays -- Historic, Philosophic, Global

$14.95 + $4 postage

* * *

Subscription for one year

$5

|