NEWS & LETTERS, May-June 2011

A Freedom Rider looks back to 'a sort of revolution'

Editor's note: This year marks the 50th anniversary of the Freedom Rides, the effort of Civil Rights activists organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and other groups to challenge racially segregated seating on interstate bus travel. The Freedom Riders were met with physical violence and arrests in the South, and stonewalling from the Kennedy administration. Abraham Bassford recounts his June 6, 1961, ride.

I remember going to the office of Liberation magazine in Greenwich Village, New York, in a basement. A.J. Muste chaired the editorial meetings. Dave McReynolds, the editorial secretary, professor Roy Finch, Dave Dellinger, who printed the magazine, and Bayard Rustin were pretty much the editorial board.

I remember one afternoon they said, "There is a CORE meeting. Do you want to come?" So we went over to Jim and Lula Farmer's apartment in the Village with their little babies running around. And I joined CORE.

We had the Woolworth's sit-ins in North Carolina at the time and I organized the support group at Wagner College, my school on Staten Island. We picketed Woolworth's and wrote letters.

I was a Christian socialist. My thinking was more or less theological.

JOINING THE FREEDOM RIDES

After my semester at college, I could plan for what might come next. My mother was upset and my father was upset because she was upset, and he couldn't do anything. The dean of the graduate school at Wagner called up my parents to let them know that he was supportive. They were a little miffed because they had gotten a postcard with a rifle sight on it as a threat.

In New Orleans we picketed Puglia's supermarket. Puglia's had a lot of Black customers but they were not allowed to work there. We joined the Consumers League picket line and got arrested. They would shift us from one police station to another to avoid our lawyers. I think there were only five lawyers in Mississippi who would defend Freedom Riders. All but one of them were Black. The NAACP Defense Fund found us the lawyers.

We spent a week or so in New Orleans until the lawyers caught up to us and we were bailed out.

Our Freedom Ride was from New Orleans to Jackson, Mississippi. Since we were Blacks and whites, we were integrated and therefore revolutionary in that place and time.

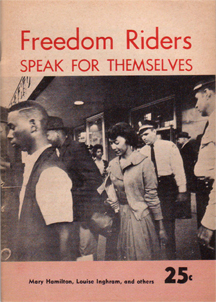

November 1961 News & Letters pamphlet

I was sitting on the bus next to Johnny Ashford, who was Black. He got the window seat. We did get to Jackson and we were told by the police that we would have to get off the bus and wait in the Greyhound Bus terminal. So we sat down in the bus terminal.

We were integrating the lily white bus terminal in Jackson and this was theoretically going to cause a ruckus. So we were arrested for disturbing the peace. That was the legal justification for our arrest. There I was being very peaceful, but I was taken for a provocateur.

I asked the judge at our trial if any of the outraged customers were armed. I told him we weren't armed and the customers didn't look very perturbed.

BEHIND BARS

We were taken to the Hinds County jail. The women Freedom Riders were in the Jackson City jail. We could hear them. They were adjacent. They would sing and so would we.

When I first got to the Hinds County jail the prisoners who were there ahead of us had been fasting out of moral outrage at being arrested. I didn't know how morally outraged I was, but I thought it does show protest. I spent at least 21 days fasting and lost a lot of weight.

There was an initial trial. The sentence was six months for what I would have called a misdemeanor. My draft status changed from 1-O (conscientious objector) to 4-F, because I had been convicted of a felony.

The jails became rather crowded. We were then moved to Parchman Penitentiary in the Delta. We were segregated from the other prisoners because we were agitators. We were racially segregated.

Jim Farmer recognized me from New York. He had been the spokesman for the people in the cell block and sort of passed the position on to me.

They had us without much of any clothing, in skivvies. Because we were singing at night without any sanction from them, they removed our mattresses and turned up the fans at night. The bunks were steel sheets with holes in them. They are not too comfortable. We made do. There might be two bunks in a cell, but we tried to sleep back-to-back to try to keep warmer.

We were kept in a big barn at the end of our stay. They moved us from the cell blocks, which were maximum security, to the barns, which were lower security.

I'm sure we were an economic burden to them, which we meant to be. I'm not sure we knew how soon we would be bailed out. I didn't know when or whether I was going to get out.

I was released after 40 days and 40 nights. I remember the warden of Parchman wanted to shake my hand and I didn't. I'm not sure that was right or wrong, but they had had some sort of a ruckus with some of us and some young men from Mississippi were hurt. They were brave. I said, "If some of your prisoners are hurt, I hope that they will get good medical attention." I didn't want to shake his hand.

FIFTY YEARS LATER

It was liberating, showing how you could act non-violently for social change. I thought it was very helpful in getting people to be a little more optimistic and braver, and think about possibilities of change. People cared about each other, even those who were different. A little identification with others helped. People became ready to speak up and act.

I couldn't not go, because people I knew had already been injured. They were braver than me. I was brought up conscious of discrimination and we didn't want to be that way. One step can lead to another. It frees you to ask, "Where do I really want to put myself? What is important?"

One of my fellow ushers at church is Black and was living in Mississippi back then. He remembers what a sort of revolution it was. He wept when he found out I was a Freedom Rider.

--Abraham Bassford

|