Written: 1909

Source: Lenin’s Collected Works,

4th Edition, Moscow, 1976, Volume 38, pp. 61-83

Publisher: Progress Publishers

First Published: 1930

in Lenin Miscellany XII

Translated: Clemence Dutt

Edited: Stewart Smith

Original Transcription & Markup:

R. Cymbala, & Marc Szewczyk,

Re-Marked Up & Proofread by:

Kevin Goins (2007)

Public Domain: Lenin Internet Archive (2003).

You may freely copy,

distribute,

display and perform this work; as well as make derivative

and commer-

cial works. Please

credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

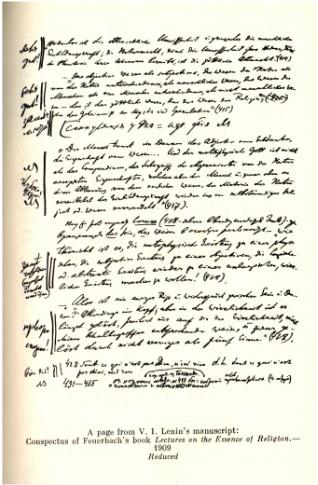

Conspectus of Feuerbach’s

book “Vorlesungen über das Wesen der

Religion” (Lectures on the Essence

of Religion) is contained in a separate

notebook whose cover was not preserved. On the

first page in abbreviated form is written L.

Feuerbach, Sämtliche Werke, Band 8, 1851;

also indicated is the press-mark—8°. R. 807. There is no indication

exactly when the Conspectus was worked out by

Lenin. V. Adoratsky has suggested that it was

written in 1909 (Lenin Miscellany

XII). The following arguments speak in favour

of this hypothesis. It has been established that

the press-mark on the first page of the Conspectus

is that of the French National Library (Paris) in

which Lenin worked from January 13 to June 30,

1909. The contents of Lectures on the Essence

of Religion borders upon those works of

Feuerbach that were used by Lenin in 1908 in

writing his book Materialism and

Empirio-Criticism, and some of Lenin’s

remarks in the Conspectus are related to

propositions formulated in his book. In the

Conspectus, for example, Lenin notes: [[Feuerbach and natural science!!

NB. Cf. Mach and Co. today]], and in

Materialism and Empirio-Criticism he

writes: “The philosophy of the scientist Mach

is to science what the kiss of the Christian Judas

was to Christ. Mach likewise betrays science into

the hands of fideism by virtually deserting to the

camp of philosophical idealism.”

(V. I. Lenin, Materialism and

Empirio-Criticism) Certain remarks in Lenin’s

Conspectus are also related to theses in his

article “On the Attitude of a Working-Class

Party to Religion,” written in May 1909.

Note that this document has undergone special formating to ensure that Lenin’s

sidenotes fit on the page, marking as best as possible where they were

located in the original manuscript.

The preface is dated 1. I. 1851.—Feu- |

8°. R. 807 | ||||

|

(VII-VIII) from their desire

(“it was only “If a revolution breaks out again and I |

Feuerbach did not understand the 1848 revolution |

||||

|

First lecture (1-11). |

|||||

| P. 2: |

“We have had enough of political as well as philosophical idealism; we now want to be political materialists.” |

Sic!! |

|||

| 3-4 |

—Why Feuerbach fled to the

seclusion of the country: the break with the “gottesgläubigen Welt”[4] p. 4 |

||||

|

(Z. 7 v. u.[5] ) (cf. p. 3 in

f.[6] )—to live with “nature” (5), ablegen[7] all “überspannten”[8] ideas. |

down with “Überspann- tes”! |

||||

| 7-11 |

Feuerbach gives an outline of his works (7-9): History of modern phi- losophy (9-11 Spinoza, Leibnitz). |

||||

|

Second Lecture (12-20). |

|||||

| 12-14 | —Bayle. | ||||

| 15: |

Sinnlichkeit[9] for me means “the true unity of the material and the spiritual, a unity not thought up and prepared, but existing, and which therefore has the same significance as |

‘sensuous- ness’ in Feuerbach |

|||

| reality for me.” | |||||

|

Sinnlich[10] is not only

the Magen,[11] but also the Kopf[12] (15). |

|||||

| (16-20: |

Feuerbach’s work on Immortality: paraphrased.) |

||||

|

Third Lecture (21-30). |

|||||

|

The objection was raised to my Essence |

|||||

|

“The unconscious being of nature is for |

|||||

|

My denial includes also affirmation.... |

|||||

|

Fourth Lecture. |

|||||

|

“The feeling of dependence is the basis |

|||||

|

“The so-called speculative philosophers |

cf. Marx und Engels[15] |

||||

|

(Fifth Lecture). |

|||||

|

— it is especially death that arouses |

|||||

|

“I hate the idealism that divorces man |

|||||

|

“As little as I have deified man in Wesen |

|||||

|

Sixth Lecture — The cult of animals (50 |

|||||

|

“What man is dependent on is ... nature, |

|||||

|

(Seventh Lecture.) |

|||||

|

By egoism I understand, not the egoism |

“egoism” and its significance |

||||

|

Idem 68 i. f. and 69 i. f. — Egoism (in the |

|||||

| (70: |

Die Gelehrten[17] can only be

beaten with their own weapons, i.e., by quo- tations) ... “man die Gelehrten nur durch ihre eigenen Waffen, d. h. Zitate, schlagen kann....” (70) |

||||

|

Incidentally, on p. 78 Feuerbach uses the expression: Energie d. h. Thätigkeit.[18] This is worth noting. There is, indeed, a subjective moment in the concept of ener- gy, which is absent, for example, in the concept of movement. Or, more correctly, in the concept or usage in speech of the concept of energy there is something that excludes objectivity. The energy of the moon (cf.) versus the movement of the moon. |

on the question of the word energy |

||||

| 107 |

i. f. ...“Nature is a primordial, pri- mary and final being....” |

||||

| 111: |

... “For me ... in philosophy ... the sensuousness is primary; but primary not merely in the sense of speculative philosophy, where the primary sig- nifies that beyond the bounds of which it is necessary to go, but primary in the sense of not being derived, of being self-existing and true.” |

the sensuousness =the prima- ry, the self- existing and true |

|||

|

...“The spiritual is nothing outside and without the sensuous.” |

|||||

| NB | in general p. 111 ... “the truth and essentiality (NB) of the senses, from which ... philosophy ... proceeds....” |

||||

| 112 ... |

“Man thinks only by means of his sensuously existing head, reason has a firm sensuous foundation in the head, the brain, the focus of the senses.” |

||||

|

|||||

| 114: |

Nature=the primary, unableitbares, ursprüngliches Wesen.[20] |

NB |

|||

|

“Thus, Die Grundsätze der

Philosophie |

|||||

|

“I deify nothing, consequently not even |

|||||

| 116 |

— Answer to the reproach that Feuer- bach does not give a definition of nature: |

||||

|

“I understand by nature the total- |

|||||

|

himself as not human.... Or, if the |

It turns out that nature= everything except the |

||||

|

of theistic faith—proves to be imme- |

supernatural. Feuerbach is brilliant but not profound. Engels defines |

||||

|

sofar as he is a being acting involun- |

more profound- ly the distinc- tion between materialism and idealism. |

||||

|

...“Nature is ... everything that you see |

|||||

|

[Here too it amounts to opposing matter |

|||||

|

“It is only man’s narrowness and love of |

|||||

| 124- |

125 Owing to their subjective needs, men replace the concrete by the ab- stract, perception by the concept, the many by the one, the infinite Σ [22] of causes by the single cause. |

||||

|

Yet, “no objective validity and exist- |

objectiv = außer uns[23] |

||||

|

...“Nature has no beginning and no end. |

|||||

|

there is no place there for God (129-130; |

|||||

|

...“The cause of the first and general |

|||||

|

“God is abstract nature, i.e., nature re- |

|||||

|

of the understanding; nature in the proper |

immediately | ||||

|

The theists see in God the cause of the |

|||||

|

...“Indeed it is only through their effects |

|||||

|

Atheism (136-137) abolishes neither das |

|||||

|

...“Is not time merely a form of the |

time and world |

||||

|

...“God is merely the world in thought.... |

|||||

|

God is presented as a being existing out- |

|||||

|

side ourselves. But is that not precisely |

being outside ourselves = independent of thought |

||||

|

...“Nature ... in isolation from its mate- |

NB nature outside, independent of matter = God |

||||

|

“To derive nature from God is equivalent |

NB | ||||

|

to wanting to derive the original from the |

theory of ‘the copy’ |

||||

|

from the thought of the thing.” (149) |

|||||

|

Characteristic of man is Verkehrtheit |

|||||

|

“Although ... man has abstracted space |

|||||

|

space and time....” (150)

“Also, it is really |

time outside temporal things = God |

||||

|

...“In reality, exactly the opposite holds |

time and space |

||||

|

presupposes something that extends, and |

|||||

|

“The question whether a God has created |

cf. Engels idem in Lud- wig Feuer- bach[27] |

||||

|

ophy, the whole history of philosophy |

153 | ||||

|

realists in the Middle Ages; between the |

|||||

|

(sic! 153) in modern times. |

|||||

|

It depends in part on the nature of people |

153 | ||||

|

“I do not deny ... wisdom, goodness, |

(materialism) contra theol- ogy and idealism (in theory) |

||||

|

Another cause of belief in God: man |

|||||

|

“That which man calls the purposiveness |

|||||

|

...“Nor have we any grounds for imagin- |

If man had more senses, would he discover more things in the world? No. |

||||

|

|||||

| 168 |

—Against Liebig on account of the phrases about the “infinite wisdom” (of God).... [[Feuerbach and natural science!! NB. Cf. Mach and Co.[28] today.]] [Back to top] |

||||

| 174- |

175-178—Nature = a republican; God = a monarch. [This occurs not only once in Feuerbach!] |

||||

| 188- |

190—God was a patriarchal monarch, and he is now a constitutional monarch: he rules, but according to laws. |

||||

|

Where does spirit (Geist) come from?— |

|||||

|

an idea of nature, too lofty an idea

of spir- |

NB (cf. Dietz- gen)[30] |

||||

|

Even a Regierungsrath[31] cannot be |

witty! | ||||

|

“The spirit develops together with the |

|||||

|

“Mental activity is also a bodily activi- |

Idem Dietzgen[32] |

||||

|

The origin of the corporeal world from the |

|||||

|

spirit, from God, leads to the creation of |

|||||

|

...“Nature is corporeal, material, sen- |

nature is material |

||||

|

Jakob Boehme = a “materialistic |

} | ||||

|

...“Where the eyes and hands begin, there |

|||||

|

(The theists) have “blamed matter or |

the necessity of nature |

||||

|

|

a germ of historical materialism |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (226): | Feuerbach says that he is ending

the first part here (on nature as the basis of religion) and passing to the second part: the qualitities of the human spir- it are manifested in Geistesreligion.[34] |

||||

| (232)— |

“Religion is poetry”—it can be said, for faith = fantasy. But do I (Feuer- bach) not then abolish poetry? No. |

||||

|

I abolish (aufhebe) religion “only in- |

NB | ||||

|

Art does not require the recognition of |

|||||

|

Besides fantasy, of great importance in |

|||||

|

(263)—In religion one seeks

consolation |

|||||

|

“A concept, however, congenial to man’s |

the necessity of nature |

||||

p. 287 |

twice in the middle: likewise “Notwendigkeit der Natur.”[38] |

NB | |||

|

Religion = childishness, the childhood |

|||||

|

Religion is rudimentary education—one |

|||||

|

can say: “education is true

religion....” |

Feuerbach against misuse of the word religion |

||||

|

Eulogy of education—(277). |

|||||

|

“Superficial view and

assertion ... that |

NB | ||||

|

I would not give a farthing for a

political |

|||||

|

Religion is innate in man (“this state- |

|||||

|

“The Christian has a free cause of nature, |

|||||

|

to cause, whereas the heathen god is

bound |

the necessity of nature [NB] |

||||

|

tematically: Notwendigkeit der Natur.) |

|||||

|

“The Christian, however, has a free

cause |

[NB] | ||||

|

keit der Natur.)) |

|||||

|

And p. 302: “...all the laws or natural |

[NB] | ||||

|

| cf. 307: “Lauf der Natur.”[39] |

|||||

|

“To make nature dependent on God, means |

[NB] | ||||

|

p. 313 (above)—“Naturnotwendigkeit”!! |

|||||

| 320: | “necessity of nature” (der Natur)... | ||||

|

In religious ideas “we have ... examples- |

what is the objective? (according to Feuerbach) |

||||

|

conception, imagination....” (328) |

|||||

|

“So Christians tear the spirit, the soul, |

Entleibter Geist[40] = God |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Religion gives (332) man an ideal. Man |

||||||

|

“Let our ideal be no castrated, disem- |

||||||

|

Mikhailovsky’s ideal is

only a vulgarised repetition of this ideal of advanced bourgeois democracy or of revolutionary bourgeois democracy. |

||||||

|

“Man has no idea, no conception, of |

Sinnlich physisch[41] ((excellent equating!)) |

|||||

|

“If one is not ashamed to allow the sen- |

||||||

|

ashamed to assert that things are not |

NB | |||||

|

then let one also not be ashamed to allow |

||||||

|

A God without the immortality of the |

||||||

|

...“Such a God is ... the God of some |

||||||

|

||||||

|

The last (30th) lecture, pp. (358-370), |

||||||

|

“from friends of God into friends of man, |

||||||

|

from Christians, who, as they themselves |

Feuerbach’s italics |

|||||

|

Next follow Additions and Notes. (371- |

||||||

|

Here there are many details, quotations, |

||||||

|

not only a singular or personal, but |

A germ of historical materialism! |

|||||

|

...“The good is nothing but that which |

||||||

|

“One has only to cast a glance at history! |

||||||

|

Where does a new epoch in history begin? |

NB NB A germ of historical materialism, cf. Cherny- |

|||||

|

the arrogant self-conceit of a patrician mi- |

shevsky[42] | |||||

|

the proletariat. So, too, the egoism of the |

NB Feuerbach’s “socialism” |

|||||

|

racy of culture, of the spirit, must be abol- |

||||||

|

These lectures were delivered from

1.XII.1848 to 2.III.1849 (Preface, p. V), and the preface to the book is dated 1.I.1851. How far, even at this time (1848-1851), had Feuerbach lagged behind Marx (The Communist Manifesto 1847, Neue Rheinische Zeitung, etc.) and Engels (1845: Lage [43]) |

||||||

|

Examples from the classics of the use |

||||||

|

Pp. 402-411—an

excellent, phi- |

||||||

|

“In the final analysis, the secret of

reli- |

NB | |||||

|

Ego are inseparably connected in man. |

NB | |||||

|

calls God, and a ‘non-Ego’ without an |

||||||

|

P. 408—an excellent quotation from Sen- |

||||||

|

Nature is God in religion, but nature |

||||||

|

as Gedankenwesen.[45]

“The secret of re- |

NB | |||||

|

of man and nature, but as distinct from the |

||||||

|

“Human ignorance is bottomless and the |

Sehr gut! | |||||

|

...“Objective essence as subjective, the |

Sehr gut! | |||||

|

different from man, as non-human essence— |

||||||

|

that is the divine being, that is the essence |

an excellent passage! |

|||||

|

Speculation in Feuerbach = ideal-

ist philosophy. NB. |

||||||

|

“Man separates in thought the adjective |

||||||

|

from the substantive, the property from |

NB profoundly correct! NB |

|||||

|

(417) |

||||||

|

The same role is played by Logic

((418)— |

||||||

|

metaphysical existence into a physical one, |

Excellent (against Hegel and idealism) |

|||||

|

...“‘Is there, therefore, an eternal gulf |

beautifully said! |

|||||

| 428: |

Tout ce qui n’est pas Dieu, n’est

rien, i.e., tout ce qui n’est pas Moi, n’est rien.[47] |

bien dit! | ||||

| 431 |

-435. A good quotation from Gassendi. A very good passage: especially 433 God = a collection of adjectival words (without matter) about the concrete and the abstract. |

NB | ||||

“The head is the house of representa- |

NB | |||||

|

tives of the universe”—and if our |

||||||

|

heads are stuffed with

abstractions, |

the individual and the uni- versal = Na- ture and God |

|||||

| 436- |

437: (Note No. 16.) I am not against constitutional monarchy, but only the democratic republic is “‘immediately reasonable’ as the form of state ‘cor- responding to the essence of man.’” |

ha-ha!! | ||||

|

...“The clever manner of writing consists,

among other things, in assuming that the reader also has a mind, in not expressing everything explicitly, in allowing the read- er to formulate the relations, conditions and restrictions under which alone a prop- osition is valid and can be conceived.” (447) |

hits the mark! |

|||||

|

Interesting is the answer to (Feuerbach’s) |

||||||

|

...“I do indeed expressly put nature |

NB “being and nature,” “thinking and man” |

|||||

|

That is why the term “the anthropolog-

ical principle” in philosophy,[50] used by Feuerbach and Chernyshevsky, is nar- row. Both the anthropological principle and naturalism are only inexact, weak descriptions of materialism. |

||||||

|

“Jesuitism, the unconscious original and |

bien dit! | |||||

|

“Thinking posits the discreteness of real- |

concerning the question of the funda- mentals of philosophical materialism |

|||||

|

||||||

|

Volume 9 = “Theogony”

(1857).[51] There

does not seem to be anything of interest here, to judge from skimming over the pages. Incidentally, p. 320, Pars. 34, 36 (p. 334) and following should be read. NB Par. 36 (p. 334)—on looking through it, nothing appears to be of interest. Quo- tations, and again quotations, to confirm what Feuerbach has already said. |

[1] Feuerbach, L., Sämtliche Werke, Bd. 8, Leipzig, 1851.—Ed.

[2] sense of place and time—Ed.

[3] of the monarch—Ed.

[4] “God-believing world”—Ed.

[5] Zeile 7 von unten—line 7 from bottom—Ed.

[6] at the end—Ed.

[7] to discard—Ed.

[8] “extravagant”—Ed.

[9] sensuousness—Ed.

[10] sensuous—Ed.

[11] stomach—Ed.

[12] head—Ed.

[13] Das Wesen des Christentums (The Essence of Christianity) by L. Feuerbach was published in 1841. In this work, Feuerbach takes a firm materialist position in philosophy.

[14] “fear”—Ed.

[15] The reference is to The Holy Family by Frederick Engels and Karl Marx, in which the authors wrote that Feuerbach outlined “in a masterly manner the general basic features of Hegel’s speculation and hence of every kind of metaphysics.” (Marx and Engels, The Holy Family, Moscow, 1956, pp. 186-187.)

[16] und folgende—et seq.—Ed.

[17] the pundits—Ed.

[18] energy, i.e., activity—Ed.

[19] evidence—Ed.

[20] underivable primordial being—Ed.

[21] Das Wesen der Religion (The Essence of Religion) by L. Feuerbach was published in 1846. Grundsätze der Philosophie der Zukunft (Principles of the Philosophy of the Future) was published in 1843.

[22] summation—Ed.

[23] objective = outside ourselves—Ed.

[24] the moral highest (= the ideal)—Ed.

[25] the natural highest (= nature)—Ed.

[26] perversity of endowing abstractions with independence—Ed.

[27] The reference is to the well-known passage on the basic question of philosophy in Engels’ book Ludwig Feuerbach and the End of Classical German Philosophy (see Marx and Engels, Selected Works, Vol. II, Moscow, 1958, pp. 369-370).

[28] Lenin contrasts here the attitude toward natural science of Feuerbach, the materialist, and of Mach, the subjective idealist. A critical evaluation of Mach’s attitude toward natural science is given by Lenin in Materialism and Empirio-Criticism (see V. I. Lenin, Materialism and Empirio-Criticism, Moscow, 1960, pp. 363-364).

[29] too lofty, too noble (!!) an idea—Ed.

[30] Josef Dietzgen developed analogous ideas. For example, in the book The Nature of the Workings of the Human Mind (Sämtliche Werke, Bd. 1, Stuttgart, 1922), in the paragraph “Spirit and Matter,” he wrote: “Long ago, mainly during early Christianity, it became customary to look with disdain upon material, sensual and carnal things, which become moth-eaten and rusty” (p. 53).

[31] a state counsellor—Ed.

[32] Josef Dietzgen wrote as follows in The Nature of the Workings of the Human Mind (Sämtliche Werke, Bd. 1, Stuttgart, 1922), in the chapter “Pure Reason or the Capacity to Think in General”: “Thinking is a function of the brain, just as writing is a function of the hand” (p. 11) and further “... the reader will not misunderstand me when I call the capacity to think a material power, a sensuous phenomenon” (p. 13).

[33] the “natural” and “civil world”—Ed.

[34] spiritual religion—Ed.

[35] feeling—Ed.

[36] comfortless—Ed.

[37] “natural necessity”—Ed.

[38] “necessity of nature”—Ed.

[39] “course of nature”—Ed.

[40] disembodied spirit—Ed.

[41] sensuous, physical—Ed.

[42] See Lenin’s notations in Plekhanov’s book N. G. Chernyshevsky (pp. 537-538, 540, 545, 546, 551-552 and 554 of this volume).

[43] Neue Rheinische Zeitung (New Rhine Gazette) was published by Marx in Cologne from June 1, 1848 to May 19, 1849.

Engels’ book The Condition of the Working Class in England was published in 1845. Regarding the significance of this book, see V. I. Lenin, pres. ed., Vol. 2, Moscow, 1960, pp. 22-23.

[44] Lenin is referring to the following passage in Feuerbach’s book Vorlesungen über das Wesen der Religion. Werke, Bd. 8, 1851, S. 411 (Lectures on the Essence of Religion,) Works, Vol. 8, 1851, p. 411): “... godliness consists, so to speak, of two component parts, of which one belongs to man’s fantasy, the other to nature. Pray!—says one part, i.e., God, distinct from nature; work!—says the other part, i.e., God, not distinct from nature, but merely expressing its Essence; for nature is the working bee, Gods—the drones.”

[45] thought entity—Ed.

[46] being, essence—Ed.

[47] All that is not God is nothing, i.e., all that is not I is nothing.—Ed.

[48] generic concepts—Ed.

[49] dramatic psychology—Ed.

[50] The Anthropological Principle—Feuerbach’s thesis that, in discussing philosophical questions, it is necessary to consider man as part of nature, as a biological being.

The anthropological principle was directed against religion and idealism. However, by considering man apart from the concrete historical and social relations, the anthropological principle leads to idealism in the understanding of the laws of historical development.

N. G. Chernyshevsky, in struggling against idealism, also took the anthropological principle as his starting-point and devoted a special work to this question under the title “The Anthropological Principle in Philosophy” (see N. G. Chernyshevsky, Selected Philosophical Essays, Moscow, 1953, pp. 49-135).

[51] The reference is to L. Feuerbach’s Theogonie nach den Quellen des klassischen, hebräischen und christlichen Altertums. Sämtliche Werke, Bd. 9, 1857 (Theogony Based on Sources of Classical, Hebrew and Christian Antiquity, Collected Works, Vol. 9, 1857). Page 320—beginning of § 34, which is headed “‘Christian’ Natural Science”; page 334 is in § 36, which is headed “The Theoretical Basis of Theism.”

| | | | | | |