Ro

Roberts, Frederick Sleigh (Lord Roberts) (1832-1914)

Military leader born in India into an army family. Took an active part in suppressing the Indian rising of 1857-58; led the colonial war against the Afghans; 1878-1880. Commander-in-chief in India 1885-93. Sent to South Africa in 1900 to regain the ground lost to the Boers.

Robeson, Paul Leroy (1898-1976)

The extraordinarily multitalented Robeson was the first world-famous singer and actor to become a political activist during his peak performing years. Robeson’s father, a runaway slave who became a minister in Princeton, New Jersey, exerted a strong influence on the young Robeson, instilling in him a quiet dignity, a love for African-American culture, and an all-embracing humanism.

An outstanding scholar-athlete at Rutgers University in 1915-19, Robeson went on to become one of the world’s leading concert singers, stage actors, and film stars in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s. During the period 1927-39, when he was based in London, his artistic growth led him to study world cultures and to support social and political movements. He sang concerts to benefit trade unions, especially the Welsh coal-miners’ union, and he came to see the connection between the struggles of the British working class and those of the oppressed colonial peoples. Robeson was introduced to socialist ideas through his friendship with George Bernard Shaw and his acquaintanceship with several leaders of the British labour Party. As a result, Robeson studied the classic Marxist writings and became attracted to the basic premises of communism.

In the early 1930s Robeson met many African students in London and developed a deep appreciation of the close links between the African and African-American cultures, learning several African languages. He also met Jawaharlal Pandit Nehru of India, with whom he formed a lasting friendship. Prompted by the desire to extend his artistic range, Robeson studied many other languages and cultures throughout the 1930s and 1940s, mastering Russian, Chinese, Hebrew, and most European languages. This focus on the centrality of culture went hand-in-hand with Robeson’s increasing radicalism – a duality that continued for the remainder of his career.

Robeson responded to the rise of German fascism by becoming one of the world’s leading antifascists. Invited to the Soviet Union in 1934 by Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein, Robeson was almost assaulted by Nazi storm troopers in Berlin as he changed trains on his way to Moscow. In the USSR he was deeply impressed by the lack of racial prejudice and by flourishing diverse cultures in the Soviet republics. These experiences and the communist leadership of the worldwide antifascist and anticolonialist struggles were the basis of his unwavering support for the Soviet people in their attempts to build socialism. The fact that Robeson viewed the Soviet Union and the world communist movement as reliable allies of the colonial liberation movements led him to form a close alliance with Communists despite his private misgivings about the Stalinist purges of 1936-38 and his disagreement with the Communist Left’s exaggerated emphasis on class priorities over “nationalist” priorities in the Third World.

In 1938 Robeson demonstrated his commitment to the fight against fascism by going to Spain to sing and speak in support of the Spanish Republic in its civil war against General Francisco Franco’s fascist rebellion. The profound effect this experience had on Robeson’s radicalization was reflected in his dramatic statement at that lime: “The artist must elect to fight for freedom or for slavery. I have made my choice; I had no alternative.” By 1939, Robeson was a key figure symbolizing on a world scale the unity of the antifascist and anticolonial struggles.

In the fall of 1939 Robeson returned from England to the United States, where he continued his highly successful concert and theater career while simultaneously becoming a leader of the civil rights movement and a spokesman for left-wing causes. He was the first major performing artist to refuse to perform for segregated audiences and to lead voter registration campaigns in the Deep South. Robeson also played an important role in support of the union-organizing drive of the CIO in the early 1940s, and in bringing black workers into the unions.

In 1946 Robeson challenged President Harry S Truman’s refusal to sponsor legislation against lynching by telling him that in the absence of federal protection blacks would exercise their right of armed self-defense. An opponent of the Cold War from its inception, Robeson attended a world peace conference in Paris in 1949 and expressed the view that black Americans should not fight an aggressive war against the Soviet Union on behalf of their own oppressors. In the wake of those remarks, the U.S. government and the media launched an attack of unprecedented ferocity against Robeson that lasted for nine years.

Robeson’s passport was revoked in 1950 and was not restored until 1958. Inquiries under the Freedom of Information Act reveal that the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of State, and numerous other U.S. government agencies compiled tens of thousands of documents on Robeson and illegally harassed him over a period of more than twenty years. Robeson was also blacklisted in the entertainment industry and prevented from appearing in professional engagements until 1957. Despite this persecution, Robeson continued to sing and speak in black churches and in the halls of the few surviving left-wing trade unions. He also wrote a book titled Here I Stand in collaboration with the black writer and journalist Lloyd I. Brown in which he outlined the program and strategy subsequently adopted by the civil rights movement and foretold the advent of the movement for economic justice.

During the anticommunist witch-hunts of the late 1940s and the 1950s, Robeson defended the rights of Communists and defied congressional committees when they compelled him to testify before them. Although he was not a member of the Communist Party, he refused on constitutional grounds to answer any questions concerning Party membership or affiliation.

Robeson remained publicly neutral concerning the USSR-China rift that began in the late 1950s, maintaining his cordial relations with both countries, and expressed no opinion about Nikita Khrushchev’s “secret speech” in 1956 denouncing Stalin’s crimes However, Robeson’s political attitude on these issues was conveyed indirectly by his personal friendship with Khrushchev and his enthusiastic support of Khrushchev’s domestic and foreign-policy reforms.

In 1958 Robeson’s passport was restored on the basis of a Supreme Court decision, and he traveled abroad for five years to reestablish his artistic career. After a successful comeback, Robeson became ill with circulatory disease, and in 1963 he returned to the United States to retire. Contrary to the claims of the media, Robeson was not disillusioned or embittered. As he put it in 1973, three years before his death from a stroke: “Though ill health has compelled my retirement, you can be sure that in my heart I go on singing.” Drawing upon lyrics he had made world famous, he continued, “I must keep laughing instead of crying, I must keep fighting until I’m dying, and Ol’ Man River, he just keeps rolling along.”

See Paul Robeson Archive.

Rodbertus, Karl Johann (1805-1875)

German economist who held socialist views. Engels deals with his views in detail in the introduction to Marx’s The Poverty of Philosophy and in the Preface to the Second Edition of Capital 2.

Also a politician and champion of Prussian Junker development along bourgeois lines. He believed that the contradictions between labour and capital could be resolved through reforms carried out by the Prussian Junker state. He did not understand the origin of surplus value and the essence of the basic contradictions of capitalism and maintained economic crises all came from low national consumption. He said the fact that agriculture did without expenditure on raw materials gave rise to ground rent.

Robespierre, Maximilien (1758-94)

Leader of the left Jacobins and head of the French revolutionary government, 1793-94. The day on which he fell from power was 9 Thermidor (July 27, 1794) in the new revolutionary calendar.

See Robespierre Archive.

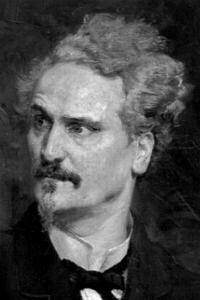

Rochefort, Henri (1831-1913)

Born in 1831 into the French nobility (his full name was the Marquis Victor-Henry de Rochefort-Lucay), Henri Rochefort began his literary career writing comedies, political journalism, and theatre criticism. His opposition to the regime of Napoleon III cost him his position at “Le Figaro,” and in 1868 he began publication of his own opposition review, “La Lanterne.” The journal was soon suppressed and Rochefort driven into exile in Belgium, where he continued to publish the magazine.

Upon his return to France in 1869 he was elected deputy from Paris, and with the fall of the Bonapartist regime was elected to the Government of National Defense in 1871. While not a member of the Commune he was a supporter, continuing his journalism during this period in “Le Mot d’Ordre.” Arrested when trying to escape Paris on May 20, 1871, during the Bloody Week, he was sentenced to deportation for life. His sentence was slightly modified by Thiers so that he would serve his incarceration on French territory and not in New Guinea, to which most of his comrades were sent.

In 1873 the new government reneged on Thiers’ agreement and deported Rochefort to the penal colony of New Caledonia. Four months after his arrival, together with five other exiled Communards, Rochefort escaped the colony and fled to Australia and, later, the United states.

Amnestied in 1880, Rochefort returned to France and political life, and was again elected deputy in 1885. But the former left-wing Rochefort had now moved to the right, and was perhaps the most important publicist for General Georges Boulanger. Boulanger’s overwhelming success in the elections of 1889 fueled a putschist movement that could very well have toppled the Republic had the general himself not lost his nerve. Boulanger went into exile in Brussels (where he committed suicide in 1891) and Rochefort followed him there.

The Rochefort who returned to France in 1895 was very little like the Rochefort of his youth. By the time of the Dreyfus affair he was a firm anti-Dreyfusard, anti-Semite and nationalist.

He died on June 30, 1913. His autobiography, Les aventures de ma vie, fill five fascinating volumes.

by Mitch Abidor

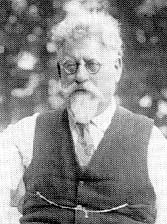

Rocker, Rudolf (1873-1958)

Libertarian anarchist writer and historian, a bookbinder by trade.

Born in Mainz, Germany, Rockere became a socialist in his youth joining the Social Democratic Party but was expelled in 1890 for his support of the left wing group Die Jungen (The Young). He observed the second congress of the Second International in Brussels in 1891 and left Germany in 1892 to escape police harassment, settling in Britain in 1895.

Though not a Jew, Rocker became deeply involved in the Jewish anarchist movement in London and became a prominent speaker and writer in the movement, editor of Dos Fraye Vort (The Free Word), Der Arbeiter Fraint (The Workers’ Friend) and Germinal. In 1907, Rocker represented the federation at the International Anarchist Congress in Amsterdam in 1907. He was interned as an enemy alien during the First World War and Arbeiter Fraint was suppressed.

In 1918 Rocker was deported to the Netherlands and returned to Germany. He became a major figure in the German and international anarcho-syndicalist movement, helping to organize the International Congress in Berlin in 1922 leading to the formation of the International Workers Association (IWA). Rocker opposed anarchist support for the Soviet government.

In 1933 Rocker left Germany again to escape persecution by the Nazis. Settling in the U.S., he directed his efforts against the “twin evils” of Fascism and Communism and supported the Allies in the Second World War. He spent the last 20 years of his life as a leading figure in the Mohegan community at Crompond, New York.

Rocker was a very prolific speaker and writer in both Yiddish and German, and he produced a great many articles and pamphlets and several books. Many of his writings were translated into Spanish and widely circulated in Latin America, but not many appeared in English. Apart from a few pamphlets, three books were published in the United States – Nationalism and Culture (1937), an essay in literary criticism called The Six (1938), and a popular survey of Pioneers of American Freedom (1949). Two more were published in Britain, Anarcho-Syndicalism (1938), and the section of his autobiography entitled The London Years (1956).

Rodichev, Fyodor Ivanovich (~1856 – ?)

Big landowner and member of the Zemstvo. A lawyer, Rodichev was a member of the Cadet party and of its central committee. Octobrist. In every convocation of the Duma Rodichev was a member. Member Provisional Committee of Duma, 1917. Emigrated.

In 1917 he became the Provisional Governments’ Governor-General of Finland. After the October Revolution when Finland was freed from Russian domination, Rodichev fled to Western Europe.

Rodzyanko, Mikhail Vladimirovich (1859 – 1924)

Russian reactionary politician; a large landowner and one of the leaders of the Octobrist party.

Rodzynako served as the chairman for the Third and Fourth Dumas. In August 1917, he supported Kornilov revolt. After the October Revolution, Rodzyanko worked to unite the counter-revolutionary groups in Russia, both foreign and local, but met with no success. He later became a White emigre.

Rodney, Walter (1942-1980)

Leading theoretician of Pan-Africanism.

Walter Rodney was born in Georgetown, Guyana on March 23, 1942. His was a working class family-his father was a tailor and his mother a seamstress. After attending primary school, he won an open exhibition scholarship to attend Queens College as one of the early working-class beneficiaries of concessions made in the filed of education by the ruling class in Guyana to the new nationalism that gripped the country in the early 1950s.

While at Queens College young Rodney excelled academically, as well as in the fields of athletics and debating. In 1960, he won an open scholarship to further his studies at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica. He graduated with a first-class honors degree in history in 1963 and. he won an open scholarship to the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. In 1966, at the age of 24 he was awarded a Ph.D. with honors in African History.

His doctoral research on slavery on the Upper Guinea Coast was the result of long meticulous work on the records of Portuguese merchants both in England and in Portugal. In the process he learned Portuguese and Spanish which along with the French he had learned at Queens College made him somewhat of a linguist.

In 1970, his Ph.D dissertation was published by Oxford University Press under the title, A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545-1800. This work was to set a trend for Rodney in both challenging the assumptions of western historians about African history and setting new standards for looking at the history of oppressed peoples. According to Horace Campbell:

“This work was path-breaking in the way in which it analyzed the impact of slavery on the communities and the interrelationship between societies of the region and on the ecology of the region.”

Walter took up his first teaching appointment in Tanzania before returning to his alma mater, the University of the West Indies, in 1968. This was a period of great political activity in the Caribbean as the countries begun their post colonial journey. But it was the Black Power Movement that caught Walter’s imagination.

Some new voices had begun to question the direction of the post-independence governments, in particular their attitude to the plight of the down-trodden. The issue of empowerment for the black and brown poor of the region was being debated among the progressive intellectuals. Rodney, who from very early on had rejected the authoritarian role of the middle class political elite in the Caribbean, was central to this debate. He, however, did not confine his activities to the university campus. He took his message of Black Liberation to the gullies of Jamaica. In particular he shared his knowledge of African history with one of the most rejected section of the Jamaican society-the Rastafarians.

Walter had shown an interest in political activism ever since he was a student in Jamaica and England. Horace Campbell reports that while at UWI Walter “was active in student politics and campaigned extensively in 1961 in the Jamaica Referendum on the West Indian Federation.” While studying in London, Walter participated in discussion circles, spoke at the famous Hyde Park and, participated in a symposium on Guyana in 1965. It was during this period that Walter came into contact with the legendary CLR James and was one of his most devoted students.

By the summer of 1968 Rodney’s “groundings with the working poor of Jamaica had begun to attract the attention of the government. So, when he attended a Black Writers’ Conference in Montreal, Canada, in October 1968, the Hugh Shearer-led Jamaican Labor Party Government banned him from re-entering the country. This action sparked widespread riots and revolts in Kingston in which several people were killed and injured by the police and security forces, and millions of dollars worth of property destroyed.. Rodney’s encounters with the Rastafarians were published in a pamphlet entitled “Grounding with My Brothers,” that became a bible for the Caribbean Black Power Movement.

Having been expelled from Jamaica, Walter returned to Tanzania after a short stay in Cuba.. There he lectured from 1968 to 1974 and continued his groundings in Tanzania and other parts of Africa. This was the period of the African liberation struggles and Walter, who fervently believed that the intellectual should make his or her skills available for the struggles and emancipation of the people, became deeply involved.. It was from partly from these activities that his second major work, and his best known — How Europe Underdeveloped Africa — emerged. It was published by Bogle-L’Ouverture, in London, in conjunction with Tanzanian Publishing House in 1972.

This Tanzanian period was perhaps the most important in the formation of Rodney’s ideas. According to Horace Campbell:

“Here he was at the forefront of establishing an intellectual tradition which still today makes Dar es Salaam one of the centers of discussion of African politics and history. Out of he dialogue, discussions and study groups he deepened the Marxist tradition with respect to African politics, class struggle, the race question, African history and the role of the exploited in social change. It was within the context of these discussions that the book, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa was written.”

Campbell also reports that

“In he same period, he wrote the critical articles on Tanzanian Ujamaa, imperialism, on underdevelopment, and the problems of state and class formation in Africa. Many of his articles which were written in Tanzania appeared in Maji Maji, the discussion journal of the TANU Youth League at the University. He worked in the Tanzanian archives on the question of forced labor, the policing of the countryside and the colonial economy. This work — World War II and the Tanzanian Economy — was later published as a monograph by Cornell University in 1976.”

Rodney also developed a reputation as a Pan-Africanist theoretician and spokesperson. Campbell says that “In Tanzania he developed close political relationships with those who were struggling to change the external control of Africa He was very close to some of the leaders of liberation movements in Africa and also to political leaders of popular organizations of independent territories. Together with other Pan-Africanists he participated in discussion leading up to the Sixth Pan-African Congress, held in Tanzania, 1974. Before the Congress he wrote a piece: “Towards the Sixth Pan-African Congress: Aspects of the International Class Struggle in Africa, the Caribbean and America.”

In 1974, Walter returned to Guyana to take up an appointment as Professor of History at the University of Guyana, but the government rescinded the appointment. But Rodney remained in Guyana, joined the newly formed political group, the Working People’s Alliance. Between 1974 and his assassination in 1980, he emerged as the leading figure in the resistance movement against the increasingly authoritarian PNC government. He give public and private talks all over the country that served to engender a new political consciousness in the country. During this period he developed his ideas on the self emancipation of the working people, People’s Power, and multi-racial democracy.

On July 11, 1979, Walter, together with seven others, was arrested following the burning down of two government offices. He, along with Drs Rupert Roopnarine and Omawale, was later charged with arson. From that period up to the time of his murder, he was constantly persecuted and harassed and at least on one occasion, an attempt was made to kill him. Finally, on the evening of June 13, 1980, he was assassinated by a bomb in the middle of Georgetown..

Walter was married to Dr Patricia Rodney and the union bore three children- Shaka, Kanini and Asha.

From http://www.guyanacaribbeanpolitics.com/

Roland-Holst, Henriette (1869-1952)

Born in Noordwijk in some obscurity, she started her intellectual life as a poet and, after her marriage to Richard Roland-Holst, a professor of art and friend of William Morris, she soon acquired a national reputation. Both her poetry and her social and political ideas developed under the close influence of Hermann Gorter. She was a close friend of Rosa Luxemburg, and her biography of Luxemburg was published in Zürich in 1937. She joined the Dutch Social Democratic Labour Party in 1897, and participated in the pre-World War I left breakaway known as the Tribunists, after the title of their paper, De Tribune. After the Russian October Revolution she became a communist and later a council communist. In 1924 she founded the short-lived Independent Communist Party. In later life disillusionment and despair at the rise of international fascism forced her into the arms of religion, and this once fine fighter for communist ideas and practice became a Christian Socialist. In old age she devoted herself mainly to literary activity.

Romanones, Count Alvaro (1863-1950)

A Spanish industrialist and large landholder, was a monarchist statesman who favored reform of the monarchy.

Romanov

Dynasty that ruled Russia from 1613 until the revolution in 1917.

Ronvroy, Claude Henri de

See: Saint Simon

Roscher, Wilhelm (1817-94)

German economist, representative of vulgar economics. Vulgar economy in his case took on the "professorial form which sets to work in an historical fashion and with wise moderation seeks to bring together the ‘best’ everywhere, not troubling about contradictions but only about completeness. ... As works of this kind first appear when political economy has completed its orbit as a science, they are at the same time the grave of this science." (Marx, Theories of Surplus Value.)

Rosdolsky, Roman (1898-1967)

Roman Rosdolsky was born in 1898 in Lemberg (now L’vov, in Ukraine) which was then part of the Austria-Hungarian monarchy. As the son of a well-known Ukrainian philologist, he grew up in a milieu of Ukrainian nationalism, but while still at high school he joined the socialist movement and became a convinced internationalist. During the First World War he and his friends founded an underground organisation – ‘The International Revolutionary Socialist Youth of Galicia’ – which edited an illegal periodical devoted to the struggle against the war. After the outbreak of the Russian revolution, this organisation provided the leaders of the Communist Party of West Ukraine (which later became a section of the Communist Party of Poland). Almost the entire leadership of this party became a victim of the purges in the early thirties, which began in the CPSU and the Soviet Union. Rosdolsky was not living there and so avoided this fate.

After the First World War, Rosdolsky emigrated, firstly to Prague and later to Vienna. In Vienna he worked for several years for the ‘Marx-Engels Institute’ (Moscow), for which he carried out research into historical sources in the Vienna Archives. At the beginning of the thirties, he joined the Trotskyist movement and till the end of his life he identified with the ideas of Trotsky.

As a member of a nationally oppressed peasant nation, Rosdolsky’s principal interest was in a Marxist analysis of the nationalities problem and the history of the peasantry. His dissertation, which gained him a PhD in political science, bore the title Marx and Engels on the problem of.the nations without a history (in German). After the seizure of power by Austro-Fascism in 1934, he had to leave Vienna and return to his native land, which in the meantime had fallen to Poland. Working at the Institute for Economic History at Lemberg University he then published ‘The village community in East Galicia and its dissolution’. (Lwow 1936, in Polish). The outbreak of the Second World War interrupted the publication of his two volume work on peasant oppression in Galicia. It only appeared in Warsaw in 1962.

At the beginning of the Second World War, Rosdolsky was living in Cracow, where he was imprisoned by the Gestapo in 1942. He spent the following years in the concentration camps of Auschwitz, Ravensbruck and Oranienburg in Germany. At the end of the war he taught for a short while in an Austrian trade union school; in 1947 he left for the USA. There his political past prevented him from gaining an academic post. By accident he discovered in an American library one of ‘only three or four copies of the original [1939-41 – SP] Moscow edition in the West’. He immediately recognised the enormous theoretical significance of this manuscript and spent several years writing a commentary on it. This commentary – The Making of Marx’s Capital, Rosdolsky’s best-known book – was only published after his death.

In the first years of his residence in the United States, Rosdolsky also completed a work he had begun with his dissertation ‘Friedrich Engels and the problem of the nations without a history’ (Hannover, 1964 Archiv fur sozialgeschichte Vol IV) in which he criticised the position of Marx and Engels on the small Slav nationalities during the revolution of 1848. He developed the argument that these nationalities went over to the camp of the Austrian monarchy, because the revolutionary Polish and Hungarian nobility shrank back from a real liberation of the peasants.

Rosdolsky also dealt with the role of the peasantry in the revolution of 1848 in a book The peasant deputies in the Constituent Austrian Reichstag 1848-9. In this work, based on exhaustive studies in the Austrian Archives, Rosdolsky explained the failure of the 1848 revolution by the inability of the liberal bourgeoisie and the nobility to carry out a ‘Jacobinist’ solution to the agrarian question.

In his last years Rosdolsky intended to write a historical work on the peace treaty of Brest Litovsk. This work was to counter the legend which had grown up since Lenin’s death that he would have supported the ‘politics of peaceful co-existence’. Rosdolsky only succeeded in finishing two chapters: one dealt with the social basis of opportunism, the material roots of the war in the imperialist epoch, and the Bolsheviks’ struggle against Kautskyism; the other, examining the strike in Vienna January 1918, was a concrete case of the extent to which the social-democrats were able to betray the struggle of the working class.

Roman Rosdolsky died in Detroit on 20 October 1967.

Steve Palmer

Rose, Frank Hubert (1857-1928)

Born in Lambeth; worked as a pattern maker. Joined the Amalgamated Society of Engineers in 1878; North-West district organizer, 1893-1900; became full-time journalist and writer. Returned to his ‘patriotic duty’ as a munitions worker during the war. Elected MP for North Aberdeen in 1918, though not endorsed by the national Labour Party. Frequently at odds with the labour movement in Aberdeen, and described those who called the General Strike as ‘Silly devils’.

Rose, Fred (1907-1983)

Born Fred Rosenberg, Canadian Communist politician and trade union organizer.

He was born in Lublin, Poland, and emigrated to Canada as a child in 1920 and joined the Communist Party of Canada while working in a factory.

Rose was jailed during the 1930s for his work organizing the unemployed, and exposing connections of the Quebec premier Maurice Duplessis with Hitler and Mussolini. He was a candidate for the Communist Party of Canada in Montreal in 1935, coming in second with 16% of the vote.

Early in World War II, the Communist Party in Canada was formally banned, then reorganized as the Labour Progressive Party. Rose won election to the House of Commons as a LPP candidate from Cartier in a 1943 by-election and was re-elected in 1945 with 40% of the vote. As a Member of Parliament, Rose proposed the first medicare legislation and the first anti-villification legislation.

A Soviet defector, Gouzenko implicated Rose as a Soviet spy, and on January 30, 1947, he was expelled from Parliament and imprisoned. Released from prison after four and a half years with his health broken, he attempted to find work in Montreal, but police had him banned everywhere. Finally he went to Poland to attempt to set up an import-export business and to obtain health treatment he could not afford in Canada. While living in Poland, his Canadian citizenship was revoked in 1957, and he was unable to return to Canada to lead the fight to clear his name.

See Fred Rose Archive.

Rosenfeld, Kurt (1877-1943)

Well-known civil liberties attorney, was a left-wing Reichstag deputy of the German social democracy. He was expelled in 1931 and helped found the centrist Socialist Workers Party (SAP) of Germany, of which he remained a leader for a short time.

Rosmer, Alfred (1885-1964)

Born Alfred Griot, son of a worker who emigrated to America after the Commune, he was originally an anarchist, then a revolutionary syndicalist and worked with Pierre Monatte at “La Vie Ouvirère.” A firm internationalist during WWI, refusing support for the war, it was during that period that he met Leon Trotsky.

An original member of the PCF, he was also present for the foundation of the Third International and was elected to its Executive Committee at its Second Congress.

Expelled from the PCF for his part in the fight against nascent Stalinism, he worked as a proofreader and was an animator of Left Opposition forces in France.

As a result of the crisis in French Trotskyism he retired from active politics in 1930, but remained close to Trotsky, and it was at his country house that the Fourth International was founded in 1938.

He dedicated himself primarily to literary work after WWII, most notably the works of Trotsky, and was a signatory of the manifesto if the 121 against the war in Algeria.

Rothschild

Famous Banking family of Austria. Founder Meyer Amschel (1743-1812) had five sons, all of them becoming Barons of the Austrian Empire in recognition of services rendered during Napoleonic wars and in the industrial and commercial development of Austria. Son Nathan became the greatest financier of the 19th Century. Decendents of this family are also noted for the finest wines produced in Bourdoux, France.

Rothstein, Theodore Aronovich (1871-1953).

Theodore was obliged to emigrate from Russia for political reasons and, from 1890, settled in Britain for the next 30 years. He joined the Social Democratic Federation in 1895, where he was very much part of its left wing. In 1901, he also joined the Russian Social Democratic and Labour Party (RSDLP) as a British based member. The RSDLP split into two factions, the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks but Rothstein was a strong supporter of the Bolsheviks. Lenin frequently visited Rothstein and his family on his own visits to London, as in 1905.

The SDF leader, HM Hyndman, was acutely disturbed by the election to the SDF executive in 1900 of Theodore Rothstein which was tinged by more than a whiff of anti-semitism. Both Rothstein and Zelda Kahan, who was also of Russian-Jewish origin, led the opposition inside the SDF to Hyndman’s growing support for British militarism arising from his mistrust of German imperial ambitions,

Theodore Rothstein supported the unity process that led to the formation in 1911, by a merger between a number of socialist groups and the SDF (which had become the Social Democratic Party in 1907) to create the British Socialist Party. Even though Theodore Rothstein was working for the Foreign Office and the War Office as a Russian translator he was strongly against the 1914-18 war. He took a prominent part in the move to oust the Hyndman and his “patriotic” national clique in the BSP in 1916 and also took part in founding of the Communist Party.

But he partly returned to Russia in 1920 and then increasingly became more involved in the USSR so that he remained there permanently. From 1921 to 1930 he was engaged in diplomatic work, starting with being the Soviet representative in Iran in 1921. He became Director of the Institute of World Economy and World Politics and, from 1939, was an Academician, receiving the Order of Lenin. Theodore also wrote a number of significant books, including on Egypt, while his From Chartism to Labourism (1929) was a pioneering work on British labour and trade union history.

(Derived in part from Graham Stevenson’s Compendium of Communist Biographies.)

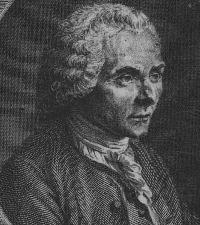

Rousseau, Jean-Jacques (1712-1778)

On "Left Wing" of French Enlightenment, Deist, Dualist (in relation to thought and matter), Sensationalist (sensations only source of knowledge), most renowned for his social theories, including the "social contract" and the source of inequality in private property.

Along with Diderot, Voltaire and others, Rousseau was a part of the Enlightenment which laid the basis for the French Revolution, and was on the "Left Wing" of that movement. Along with Voltaire, Rousseau was a Deist, and his contribution to philosophy as such is modest.

However, Rousseau’s ruthless and thorough-going social criticism makes an important contribution to laying the basis for materialism to break out of the mechanical view of the relation of consciousness and Nature which predominated up to that time. Descartes, Bacon, Hobbes and Locke all see only an individual human animal perceiving Nature with brain and senses. Under these conditions, the origin of concepts is mystified.

Rousseau’s most famous work is Discourse on the Origin of Inequality Among Men, in which he shows how social conditions, and in particular private property, lead to inequality and the whole range of social ills.

Emile (and the later Sophie) are unstructured, almost stream-of-consciousness works in which Rousseau uses narrative and dialogue with a fictious son (and daughter) to expound his theory of child development, pedagogy and sociology. He shows how upbringing and social environment shape a person’s personality and views. He emphasises the need to live and develop in conformity with Nature.

The excerpt included is found midway through Emile and in it Rousseau presents his philosophical views on the questions of matter and consciousness.

Further Reading: Engels’ comments in Anti-Duhring

See Jean-Jacques Rousseau Archive

Roux, Jacques (d. January 20 1794)

French priest who became a leader of the popular democratic Enragés during the French Revolution.

At the outbreak of the Revolution in 1789, Roux was a vicar of a parish in Paris. Soon he began preaching the ideals of popular democracy to crowds in Paris. In 1791 he was elected to the Paris Commune, and in May he demanded that hoarders be put to death. He led food riots in Paris in February 1793 and was a leader of the sansculotte crowds that forced the National Convention to expel the Girondinists on June 2 1793.

The Jacobins were reluctant to institute the stringent economic controls demanded by Roux, and on June 24 Roux denounced the Convention for its failure to curb hoarders and war profiteers. He was blamed for the soap riots that broke out in Paris the following day, and on July 28, Robespierre denounced Roux as a foreign agent and counter-revolutionary. Shortly thereafter Roux was expelled from the Commune and the Cordeliers Club. The Convention then took action against monopolists and hoarders and requisitioned food supplies for the populace of Paris in July and August 1793. The Enragés program was taken over by left-wing Jacobins under Jacques Hébert, and on September 5 Roux was arrested. In January 1794, he committed suicide in Bicêtre prison.

See Jacques Roux Archive.

Rowbotham, Sheila (1943-)

British socialist feminist. After studying history at Oxford University Sheila taught in adult education, further education and schools. Her political activism began with her involvement in the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and the British Labour Party’s youth wing, the Young Socialists. Disenchanted with the direction of party politics she immersed herself in a variety of left-wing campaigns, including writing for the radical political newspaper ‘Black Dwarf’.

In 1969, she published her influential pamphlet ‘Women’s Liberation and the New Politics’ which argued that Socialist theory needed to consider the oppression of women in cultural as well as economic terms. She was one of the small group who pioneered women’s history. She worked at the Greater London Council in the early 1980s developing economic and social policy and editing a newspaper for the Economic Policy Unit called ‘Jobs for a Change’. During the 1980s she worked as a consultant for the United Nations University’s World Institute for Economic Research (WIDER). After part time work at the Universities of Amsterdam and Kent, she came to Manchester as a Simon fellow in 1993-4 and again as a University Research Fellow in 1995. She has lectured extensively in the US, Canada, Brazil, Europe and India and her work has been translated into many languages, including Chinese, Arabic and Hebrew. In 2004 she was elected a fellow of the Royal Society of Arts.

Roy, Evelyn Trent (1892-1970)

Evelyn Trent-Roy, who also went by the alias ‘Shanthi Devi,’ was the first wife and political collaborator of the influential Indian Communist leader Manabendra Nath Roy.

Evelyn Trent met M. N. Roy when he visited the home of Stanford University’s president, Dr. David Jordan, in 1916. Soon afterward, they moved to New York where they studied Marxism.

After the U.S. entered the First World War, Indian revolutionaries were detained by U.S. authorities as potential agents for Germany. To avoid the possiblity of prosecution under the anti-conspiracy laws, the Roys fled to Mexico where they helped found the Communist Party of Mexico. They attended the Second Congress of the Comintern in 1920 as part of the Mexican delgation. Later that same year she helped found the émigré Communist Party of India in Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

Further Reading: Evelyn Roy Archive.

Roy, M N (March 21, 1887-January 25, 1954)

Narendranath Bhattacharya, who later assumed the name Manabendra Nath Roy, was an Indian Communist leader. He was politically a product of militant nationalism which had emerged and crystallised in the Indian National Congress towards the end of the nineteenth century. Leftism in India has been a combination of diverse strands of approaches, traditions and practices. M. N. Roy, a principal figure in revolutionary nationalism in his early years, eventually became the forerunner of Marxian politics in India. The Lenin-Roy debate on the national and colonial question continues to plague the communist movement to the present day. Roy directed from abroad the communist movement in India and sent programmes to the National Congress during its heyday of NCD and CD (Civil Disobedience). He added an operative part to the national struggle by a scheme to turn the Congress into a constituent assembly and as a state within a state to capture power in the pattern of the French Revolution. He persistently tried to radicalise the Congress and raised the slogan of alternative leadership.

Arriving in India in early 1930s he led intensive movements of workers and peasants. Before long, a cleavage developed between Roy’s adherents called the Roy group on the one hand, and the CSP and CPI on the other, on various issues, ideological and organisational. Shortly, the Left groups had to accept such courses of action for which they had castigated Roy earlier.

On the outbreak of the World War II, the Right and the Left were confused about the Congress policy, while Roy characterised the war anti-fascist and supported the allies, foreseeing that India would attain independence following the defeat of the Axis powers and inevitable weakening of the economic base of the British Imperialism. Roy was finally vindicated.

Roy had a leading role in revolutionary movements in India, Mexico, the Middle East, the Soviet Union, Indonesia and China. Like Marx he was both and activist and a philosopher; in fact Lenin called him “the Oriental Marx.”

Roy tried to organize an armed insurrection in India in 1915; founded the Communist Party of Mexico (1919) and the emigré Communist Party of India in Tashkent (1920); rose to occupy the highest offices of the Communist International and led the Comintern’s delegation to China (1927). At the same time he authored such Marxist classics as India in Transition (1922), The Future of Indian Politics (1926) and Revolution and Counter-revolution in China (1930); and founded the organ of the emigré Communist Party of India, The Vanguard (and later The Masses) and edited it for seven years (1922-28).

Roy broke with the Communist International in 1929 having publicly opposed the extreme left sectarian policy adopted at its Sixth Congress. Returning to India he spent six years in various prisons during which he wrote a 3000-page draft manuscript provisionally titled The Philosophical Consequence of Modern Science. On his release he campaigned against every variety of authoritarianism, supported the anti-fascist war, drew up a Draft Constitution for free India and the outlines of a decentralist people’s plan for economic development.

Disillusioned with both bourgeois democracy and communism, he devoted the last years of his life to the formulation of an alternative philosophy which he called Radical Humanism and of which he wrote a detailed exposition in Reason, Romanticism and Revolution. He wrote a lot of pamphlets for beginners. He was an active Marxist for the most part of his life, but he abandoned Marxist philosophy and indulged in pleading meaningless fellow-feelings among different religions of India and promoting pale humanistic thoughts. He traced morality to biological roots and suggested that human progress depended on progress towards liberty and truth.

In 1948, he launched the Radical Humanist Movement in India, which in 1952 joined with other humanist groups in Europe and America to found the International Humanist and Ethical Union. Roy was one of the first Vice-presidents. The humanist centre in Bombay is called the M N Roy Memorial Human Development Campus.

By Hasan; most of the facts in this sketch have been taken from: Leftism in India; M. N. Roy and Indian Politics, 1920-1948, by S. M. Ganguly, South Asia Books, Box 502, Mo. 6205, USA.

Roy, Haradhan (1926-present)

Born Napur (District Burdwan, West Bengal), son of Rakhal Chandra Roy. Educated Raniganj High School, Raniganj. Member, Forward Block, 1946-48. Joined CPI, 1954, and CPI(M), 1964. Assistant Secretary, Refractory and Ceramic Workers Union, 1948. Founding Member and General Secretary, Colliery Mazdoor Sabha of India, 1952-2004. Member, All-India Engineering Workers Federation, 1956-57. Member of Central Committee, AITUC, 1957-64. Member of Working Committee, Bengal Provincial Trade Union Congress, 1957-64. Member, All-India and State Working Committees, Center for Indian Trade Unions, 1964-2004. General-Secretary, Jyoti Prakash Glass Mazdoor Union. Vice-President, All-India Coal Workers Federation. General Secretary, Aluminium Mazdoor Union, since 1967. Member, West Bengal Legislative Assembly, 1967-87. Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha), 1989-97. Quit CPI(M), 2004, in opposition to privatization of coal mines. Formed new colliery union under Sara Bharat Khani anchal bachao trade union. Resides in Asansol, West Bengal.

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin

Roy, Karuna Kant (?– 1991)

Party pseudonym: Ranadhir.

Born in Sylhet (Bengal). Educated Calcutta and Kashi Vidyapith, Benares. Joined the Civil Disobedience movement, 1930 while still a student and was beated by the police and jailed. Joined Bolshevik Leninist Party of United Provinces and Bihar, 1939. Editor, Awaz [The Voice], 1940. Founding member, Bolshevik Leninist Party of India, 1942. Arrested in Benares during Quit India revolt, 1942. Moved to Bombay, 1943. After Independence, became a trade unionist, West Bengal Khadi and Village Industries Commission, Calcutta.

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin

Roy, Purnangshu K.

Nickname: Nitai

Educated Calcutta. Joined Bolshevik Leninist Party of India, 1942. Delegate, Bolshevik Leninist Party of India conferences, 1947 and 1948. Leader of “anti-entry” faction. Entered SP with BLPI, 1948. Withdrew from active politics after 1952 elections. Went to UK in 1957 and became a physicist. Worked with the Trotskyist group in the British Labour Party led by Gerry Healy, 1957-59. Developed ankylosing spondilitis, a debilitating and painful form of rheumatoid arthritis, and died sometime in the mid ‘eighties.

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin