Ki

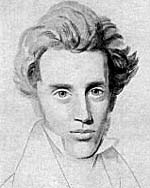

Kierkegaard, Søren (1813-1855)

Danish religious philosopher regarded as the founder of existentialist philosophy. He is famous for his attack, on the one hand on the Church establishment, and on the other, upon all systematic rational philosophy, particularly Hegel, on the grounds that actual life cannot be contained within an abstract conceptual system. With this stance, he intended to clear the ground for an adequate consideration of faith and Christianity. See his early attack on Hegel: Concept of Dread.

Kilian, Otto (1879–1945) .

Printer, in SPD (Sozialistische Partei Deutschlands, Social-Democratic Party) in 1902, full-timer in 1906, then journalist. Conscript during 1915–18, joined USPD in 1917. Chairman of workers’ council in Halle, in 1918, sentenced in March 1919 to three years imprisonment, amnestied. On USPD Left, in VKDP (Vereinigte Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands/United Communist Party of Germany) in 1920. Opposed March Action, remained in Party, then activist of the Left, expelled in 1927, made ‘self-criticism’, readmitted, resigned and organised Leninbund. Arrested in 1933, in a concentration camp, died of typhus in Bergen-Belsen shortly before end of War.

Kippenberger, Hans (also known as Leo and Alfred Langer, 1898–1937) .

Secondary education, bank employee. Lieutenant during war. Resumed studies after war, worked as press correspondent. In USPD in 1918, in VKDP (Vereinigte Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands/United Communist Party of Germany) in 1920. Joined clandestine apparatus in 1922, played important role in 1923 in military preparations, and had leading role in Hamburg uprising. Took refuge in Moscow, studied in military school. In illegality in Germany during 1924–8, organised KPD’s Military Apparatus. Deputy in Reichstag during 1928–33. Important role in illegality in Germany during 1933–5, recalled to Moscow, shot after secret trial on 3 October 1937. Officially rehabilitated in USSR in May 1957, but not in DDR.

Kirov, Sergei (1886-1934)

Sergei Kirov was born in Urzhum, Russia, on 15th March, 1886. His parents died when he was young and he was brought up by his grandmother until he was seven when he was sent to an orphanage.

At the Kazan Technical School he became a Marxist and joined the Social Democratic Party in 1904. He took part in the 1905 Revolution in St. Petersburg. He was arrested but was released after three months in prison.

Kirov now joined the Bolshevik faction of the Social Democratic Party. He lived in Tomsk where he was involved in the printing of revolutionary literature. He also helped to organize a successful strike of railway workers.

In 1906 Kirov moved to Moscow but he was soon arrested for printing illegal literature. Several of his comrades were executed but he was sentenced to three years in prison. The prison had a good library and during his stay he took the opportunity to improve his education.

Kirov returned to revolutionary activity after his release and in 1915 he was once again arrested for printing illegal literature. After a year in custody he moved to the Caucasus where he stayed until the abdication of Nicholas II in March, 1917.

After the October Revolution Kirov was sent to fight the anti-Bolshevik forces in the Caucasus. He fought in the Red Army until the defeat of General Anton Denikin in 1920.

In 1921 Kirov was put in charge of the Azerbaijan party organization and the following year helped organize the Transcaucasian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic.

Kirov loyally supported Joseph Stalin and in 1926 he was rewarded by being appointed head of the Leningrad party organization. He joined the Politburo in 1930 and now one of the leading figures in the party, and many felt that he was being groomed for the future leadership of the party by Stalin.

In the summer of 1932 Joseph Stalin became aware that opposition to his policies were growing. Some party members were publicly criticizing Stalin and calling for the readmission of Leon Trotsky to the party. When the issue was discussed at the Politburo, Stalin demanded that the critics should be arrested and executed. Kirov, who up to this time had been a staunch Stalinist, argued against this policy. When the vote was taken, the majority of the Politburo supported Kirov against Stalin.

In the spring of 1934 Kirov put forward a policy of reconciliation. He argued that people should be released from prison who had opposed the government's policy on collective farms and industrialization. Once again, Joseph Stalin found himself in a minority in the Politburo.

After years of arranging for the removal of his opponents from the party, Joseph Stalin realized he still could not rely on the total support of the people whom he had replaced them with. Stalin no doubt began to wonder if Kirov was willing to wait for his mentor to die before becoming leader of the party. Stalin was particularly concerned by Kirov's willingness to argue with him in public. He feared that this would undermine his authority in the party.

As usual, that summer Kirov and Joseph Stalin went on holiday together. Stalin, who treated Kirov like a son, used this opportunity to try to persuade him to remain loyal to his leadership. Stalin asked him to leave Leningrad to join him in Moscow. Stalin wanted Kirov in a place where he could keep a close eye on him. When Kirov refused, Stalin knew he had lost control over his protégé.

Sergei Kirov was assassinated by a young party member, Leonid Nikolayev, on 1st December, 1934. Stalin claimed that Nikolayev was part of a larger conspiracy led by Leon Trotsky against the Soviet government. This resulted in the arrest and execution of Genrikh Yagoda, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, and fourteen other party members who had been critical of Stalin.

In The Granat Encyclopaedia of the Russian Revolution Kirov wrote:

The prison library was quite satisfactory, and in addition one was able to receive all the legal writings of the time. The only hindrances to study were the savage sentences of courts as a result of which tens of people were hanged. On many a night the solitary block of the Tomsk country prison echoed with condemned men shouting heart-rending farewells to life and their comrades as they were led away to execution. But in general, it was immeasurably easier to study in prison than as an underground militant at liberty.

From Spartacus Schoolnet.

Kiselev, Aleksey Semenovich (1879 - 1937)

Born near Ivanovo-Voznesensk (a town in the district of Vladimir, with an 1887 population of 22,000), beginning in 1893 Aleksey worked as a machinist (slesarem) in a textile factory. In 1898 he joined the RSDLP, working for the party in Ivanovo-Voznesensk, Moscow, Kharkov, Baku, and Odessa. He was arrested on multiple occasions. In 1914 Aleksey joined the Central Committee of the party, and shortly thereafter he was arrested again and sent to Siberia. Knowing he would be forcibly drafted into the army at the outbreak of World War One, Aleksey escaped prison and moved from city to city in Siberia to avoid capture. In the General Amnesty of the February Revolution, he returned to the east in 1917 and resumed his position of the Central Committee. He later became only a candidate (alternate) member of the Central Committee, and served this role from 1917-19, 1921-23, and 1925-34, actively filling in at various times (from February 1919 to April 1920; in 1924 as secretary).

Here in Ivanovo-Voznesensk, without the softening effect of any intermediate class, the two antagonistic sides--labour and capital--stood confronted. The issue was as clear as clear could be, and that is why it was so easy to carry on our Bolshevik propaganda there. Here we had no serious conflict with any organized groups of Mensheviks or Socialist-Revolutionaries. That is why the Ivanovo-Voznesensk proletariat, led by some of the most prominent comrades in our ranks, was always in the forefront of the proletarian revolution.

Cecilia Bobrovskaya

Twenty Years in Underground Russia: Memoirs of a Rank-and-File Bolshevik

In 1918 Kiselev became a member of the presidium of the VSNKh (Supreme Council for the National Economy of the USSR). Also in the Summer of 1918, he led the political department of the Orenburg Red Army division. In 1919, in addition to these roles and serving on the CC of the party, Kiselev also served on the Council of People's Commissars for Turkestan. Beginning in April 1920, he left his position on the CC of the party to become Chairman of the All-Russia Miner's Union in Turkestan.

In 1920 Kiselev supported the Worker's Opposition, but conformed to party discipline when the group was banned. From 1923-24 he served as a member of the presidium of the TSKK (Central Control Commission of the Communist Party). In 1923 Kiselev also became the People's Commissar of the Workers and Peasant Inspection of the RSFSR, and a reserve member to the same role for the USSR. From 1925-34, he again became a candidate member of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Little else is know about his life during this time.

On September 7, 1937, after 20 years of service to the Soviet government, Kiselev is arrested for allegedly belonging to an "anti-Soviet counter-revolutionary organisation". Uncharacteristic of the slaughter of Old Bolsheviks who led such distinguished and long careers, Kiselev is almost immediately shot after his arrest, on October 30, 1937, in Moscow.

In 1956, he is among the first to be officially "rehabilitated" after Stalin's death.

Kitchener, Horatio Herbert (1850-1916)

British soldier who became Commander-in-Chief of South Africa in 1900, where he pioneered the use of civilian repression (e.g. concentration camps) as a method of colonial warfare. Commander-in-Chief 1902-9 and then British Agent (i.e. Governor) in Egypt until 1914 when he became War Secretary and organized Britain's first conscript army for the war in Europe. Died when the boat on which he was travelling was torpedoed in 1916.

Kıvılcımlı, Hikmet (1902-1971)

Turkish communist. The founder of the Homeland Party (Vatan Partisi).

Hikmet Kıvılcımlı was born in 1902, Priştina, Kosovo, within the borders of the Ottoman Empire. He attended high-school at Vefa Lisesi in the early twenties he participated as a fighter in the Turkish independence war in Anatolia. He then returned to ıstanbul and studied medicine as a military student. At this time he joined the Türkiye Komünist Partisi (TKP).

In 1925 he was elected to the Central Committee of the Party. He was arrested and sentenced to prison for 10 years, but one year later pardoned in the General Amnesty. But at the end of the 1929 he was arrested again. He remained in Elazig prison until 1932. ın prison he wrote a lot of theoretical articles and pamphlets. His first political essays were published in Menteşe, and Aydınlık. Kıvılcımlı translated also many publications of the writings of Karl Marx and published them as pamphlets of the ‘Marksizm Bibliyotegi’ (Library of Marxism), a publishing house he founded in 1932. ımprisoned several times (1925, 1927, 1929, 1934, 1938-1950), he spent twenty years of his life in prison. But in 1938 his books and publications were found among the students in the War School, and in what became known as the Navy Cadets Trial, he was sentenced to 15 years in prison together with Nazım Hikmet.

He was pardoned in 1950 in general amnesty, and he then joined the re-foundation of the Communist Party. Critical of the party policy, he distanced himself from the TKP. ın 1954, under the oppressive regime of the Democrat Party, he founded the Vatan Partisi (Homeland Party). ın 1958 the party was banned; after the military putsch in 1960 he founded the newspaper Sosyalist which attempted to unite all the revolutionary forces. Later, in 1965, he established the ‘Tarihsel Maddecilik Yayınları’, a publishing house which published his own works. ın 1967, he was the founder of the ‘İşsizlik ve Pahallılıkla Mücadele Derneği’ (İPSD). Because of a warrant of arrest by the military regime after the coup in 1971 he left the country by a fishing-boat. At first he went to Cyprus, than over Syria he reached Yugoslavia. Already severely ill before he left Turkey, he died of cancer in Beograd in 1971.

All through his life he wrote, translated and noted down on virtually every piece of paper within his reach. His best known work is ‘Tarih Tezi’, his magnum opus, written in 1965. He translated a substantial part of Das Kapital into Turkish. Other important works are: ‘Yol: TKP'nin Eleştirel Tarihi’ (The Way: critical history of the Communist Party of Turkey), containing a series of texts, already written for the Central Committee of the TKP in 1932, and posthumously published by F. Fegan in 1982; ‘Türkiye İşçi Sınıfının Sosyal Varlığı’ (The Social Existence of the Turkish Working Class) 1935; ‘Kim suçlamış? Brejnev'e mektup’ (Who accused? Letter to Brezhnev) 1971, 1979 and a many articles in Menteşe, Aydınlık, Sosyalist, Türk Solu, and Ant.

Kıvılcımlı’s political inheritance was administrated by Fuat Fegan.