Be

Beard, Mary (1876-1958)

Mary Ritter Beard was born in Indianapolis on 5 August 1876, the third of six children and the elder of two daughters of Narcissa (Lockwood) and Eli Foster Ritter. At sixteen she left home to attend De Pauw University in Asbury, Indiana, where she studied political science, languages, and literature. She graduated in 1897 and taught high school German until 1900 when she married Charles Austin Beard, whom she had met at De Pauw. Mary Beard accompanied her husband to Oxford, and both were active politically as well as academically. Charles helped organize Ruskin Hall, the "free university" aimed at workingmen, and Mary became involved with the British women’s suffrage movement. They returned to New York in 1902. Their daughter Miriam was born in 1903. The following year the Beards enrolled at Columbia University, but Mary quit soon after to take care of their child and volunteer for progressive causes.

Following the birth of her son William in 1907, Mary Beard became an organizer for the National Women’s Trade Union League. From 1910 to 1912 she edited the suffragist periodical The Woman Voter, and after that worked with the Wage Earner’s League. She was a member of the militant faction of the suffrage movement led by Alice Paul from 1913 to 1919, and she worked on several progressive causes. During this period, Charles taught at Columbia University, but he resigned in 1917 in protest of the firing of anti-war faculty. Charles helped establish the New School for Social Research (later joined by refugees from the Franfurt School) and both Beards helped found the Workers Education Bureau, but by the early 1920, the Beards generally worked outside of academic institutions.

Following her resignation from the National Woman’s Party in 1917, Mary Beard devoted her skills and efforts to writing and lecturing, rather than public political activity. Her first book, Woman’s Work in Municipalities (1915) and her second, A Short History of the American Labor Movement (1920), focused on social reform and the working class. With Charles, she co-authored The Rise of American Civilization (1927), a groundbreaking text that integrated political, economic, social, and cultural histories with a progressive vision of America’s past and distinctive national character. The two collaborated on several books that would become some of the most enduringly significant American history texts, but by herself, Mary pioneered the field of women’s history. She was appalled by the omission of women from the historical record, and she wrote about and promoted the recognition of women’s achievements in the present day and the past, in the U.S. and internationally. She authored and edited Understanding Women (1931), America Through Women’s Eyes (1933), A Changing Political Economy as It Affects Women (1934), and Women as Force in History (1946), among others.

Rather than concentrating on grievances and questions of the subjugation of women, Beard’s work promoted women’s contributions to the formation of society and brought to light a long-neglected past. To this end in the early 1930s, she collaborated with Hungarian pacifist feminist Rosika Schwimmer to organize the World Center for Women’s Archives (WCWA). Beard quoted French historian Fustel de Coulanges for the motto of the WCWA: "No documents, no history," and she envisioned an archive of women’s papers and organizational records that would provide a foundation for women’s history as an academic field as well as serve as a public good. Beard and Schwimmer raised funds, founded a board of directors, and collected documents from their network of women activists. The WCWA was headquartered in New York but collected on an international level. It was a well-publicized effort, and though the collection specialized in material from the pacifist movement, Beard worked to realize a broader conception for a collection representing the range of women’s activities. Factionalism among WCWA supporters, shaky financial support, and an increasingly militaristic atmosphere in the U.S. and abroad forced the dissolution of the WCWA in the early 1940s.

This development was very discouraging to Beard, but fortunately, the WCWA generated momentum for developing institutions of women’s history. Beard worked closely with Smith College archivist Margaret Grierson to create the Sophia Smith Collection, one of the world’s largest women’s history manuscript collections, founded in 1942, and she worked with Harvard historians to create the eventual Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe. These two institutions received many of the WCWA documents, as did several smaller collections. Together, they carried on the WCWA mission, at least partly due to Beard’s influence.

Neither of the Beards avoided controversy in their writings or public stands. Though both were well-respected historians, they increasingly drew criticism for their pacifist and progressive politics in the years surrounding World War II. Charles Beard died in 1948, and Mary Ritter Beard died on 14 August 1958. Both Beards have had enduring reputations as incisive historians, and they are recognized for their pioneering work in social history. Mary Beard especially has been celebrated for her work to promote women’s history.

See Mary Beard Archive.

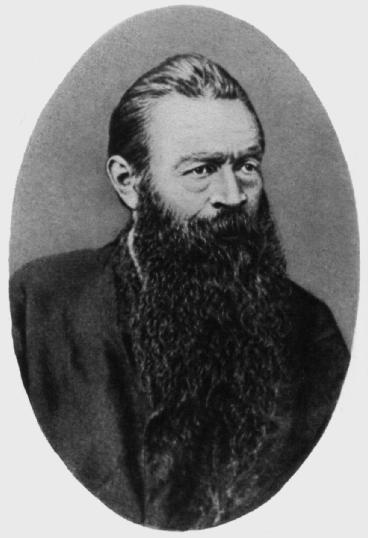

Bebel, August (1840-1913)

A worker and Marxist revolutionary, Bebel co-founded German Social Democracy with Wilhelm Liebknecht in 1869. Bebel had trained as a cabinet maker, and in 1863, at the time of the founding of Lassalle’s German Workers’ Association, he found "socialism and communism" "totally unfamiliar concepts, double-duth words". Bebel was a member of the Reichstag from 1867. Sentenced with Liebknecht to two years imprisonment for "treason" (opposition to Franco-German War) in 1872. After the GSD merged with the Lassalleans in Gotha in 1875, Bebel remained the unquestioned leader. His fiery parliamentary speeches – from 1868 he was continuously a member first of the North German and later the German Reichstag – are part of the history of German social democracy, as are also his books, above all his autobiography From My Life and Woman and Socialism

See the August Bebel Archive.

Becker, Karl (1894–1942) .

Printer, son of activist, member of Socialist Youth in 1909 and SPD (Sozialistische Partei Deutschlands, Social-Democratic Party) in 1912. During war was a leader of radical Left in Dresden and then in Bremen. Arrested in 1917, freed by November Revolution, was leader of a workers’ council. Delegate from IKD to founding conference of KPD (Kommunistischen Partei Deutschlands/German Communist Party) . Supported ultra-left majority. Co-leader of opposition in 1919 and co- founder of Allgemeine Arbeiter Union. Expelled at Heidelberg, did not join KADP (Kommunistische Arbeiterpartei Deutschlands/Communist Workers Party Of Germany) , returned to KPD(S) under Radek and Frölich’s influence in March 1920. Made several visits to Moscow. From 1921 was editor of Hamburger Volkszeitung, in 1923 in charge of the Wasserkante and North-West region, member of right tendency. Appears to have gone underground at end of 1923 and taken refuge in Moscow. Returned in 1925, member of ‘conciliator’ group, elected to Prussian Landtag in 1928. Made ‘self-criticism’. Went underground in 1933, then emigrated to France. Betrayed by Vichy, condemned to death, executed in Plötzensee.

Becker, Hermann Heinrich (1820-1885)

Cologne writer and communist.

Becker, Johann Philipp (1809-1886)

German revolutionary in the 1830s and 1840s and friend of Karl Marx and Engels. Later resided in Switzerland. Prominent in the First International.

Becker, Maurice (1889–1975)

Radical political artist best known for his work in the 1910s and 1920s for such publications as The Masses and The Liberator.

Early years

Maurice Becker was born in Nizhni-Novgorod, Russia, the son of ethnic Jewish parents. The family emigrated from Russia to the United States in 1892, moving to the Jewish community of the Lower East Side of New York City.

The young Maurice took night classes in bookkeeping and art while working days as a sign painter. He worked as an artist for the New York Tribune from 1914 to 1915, and for the Scripps newspapers from 1915 to 1918. He also contribute artwork on a freelance basis to a broad range of contemporary publications, including Harper’s Weekly, Metropolitan magazine, and The Saturday Evening Post.

Radical art

Maurice Becker is best remembered as an illustrator for radical magazines, most famously for the New York political and artistic magazine The Masses, to which he began to contribute in 1912. Becker cartoon from March 1913 issue of The Masses.

He married Dorothy Baldwin, an active Socialist, in 1918. That same year he became a conscientious objector to American participation in World War I. He fled to Mexico to avoid the draft. He was arrested upon his return to the United States in 1919 and was tried, convicted, and sentenced to 25 years of hard labor, of which he served 4 months at Fort Leavenworth prior to commutation of his sentence.

Becker was a frequent contributor to the radical press, publishing his art in such periodicals as Revolt, The Toiler, New Solidarity, The Blast, Survey Graphic, The New York Call and The New Masses. Becker’s work, which often made use of the muted tones of graphite or charcoal, was likewise generally softer in political tone than the more hard-edged and biting work of his peers, who included Art Young, Fred Ellis, Robert Minor, Hugo Gellert, and William Gropper.

From 1921 to 1923, Becker lived in Mexico, where he worked as an artist for El Pulsa de México, an English-language magazine. After that time, he dedicated himself to painting full time, essentially ending his career as a political artist for magazines. He did occasionally contribute art to political publications after that date, however, such as an apolitical drawing entitled "Summer," which ran in the August 1926 issue of The New Masses.

Becker remained a political radical throughout his life and was either a member or a fellow traveler of the Communist Party USA for many years. He visited the Soviet Union in 1931. In 1932 Becker Joined The League of Professional Groups for Foster and Ford, officially endorsing Communist candidate William Z. Foster for President of the United States. In 1936 he likewise endorsed Communist candidate Earl Browder as a member of the Committee of Professional Groups for Browder and Ford. His name appeared on the letterhead of the Artists’ Front to Win the War, a mass organization closely linked to the Communist Party, and he was a signatory to the call for formation of the American Artists’ Congress, a party-backed initiative.

Maurice Becker died in 1975.

Bedacht, Max, Sr (1883—1972)

German-born American revolutionary socialist politician and journalist who helped establish the Communist Party of America.

Max Bedacht, Sr. was of ethnic German mother in Munich, Germany on October 13, 1883. He was the son of a single mother who worked as a domestic servant and was raised a Catholic by a maternal aunt and uncle. He apprenticed and worked as a barber in Germany and Switzerland. He organized fellow journeymen barbers into a union during his European years. In 1905 he joined the Swiss Social Democratic Party.

Bedacht emigrated to the United States in 1908 and joined the Socialist Party of America (SPA) during that same year.. In June of 1913 he moved to San Francisco to become the editor of the German-language labor newspaper Vorwärts der Pacific Küste (Forward of the Pacific Coast), a job which he retained until the paper’s termination in 1917 due to draconian postal regulations being placed on the foreign language press during World War I. He briefly moved to South Dakota to edit a paper called The New Era following the demise of the Vorwärts, but soon returned to San Francisco when he found that publication unviable, taking up the barbers’ shears again.

Bedacht was long an adherent of the so-called impossibilist wing of the Socialist Party, placing his faith in socialist revolution rather than the ameliorative reform of elected officials. As was the case with many radicals in America, Bedacht was inspired by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and was an early adherent of the 1919 Left Wing Manifesto written by Louis C. Fraina and the Left Wing Section of the Socialist Party which emerged in conjunction with that document. Bedacht was a Left Wing candidate for the SPA’s governing National Executive Committee in 1919 and a delegate to the SPA’s pivotal 1919 Emergency National Convention.

At the Chicago convention in August 1919, the Left Wing California delegation was challenged at the time the gathering was convened, placing the delegates in limbo, their fate held in the mercy of a committee firmly controlled by the “Regular” faction of National Executive Secretary Adolph Germer and James Oneal. The Credentials Committee, headed by Judge Jacob Panken of New York City, stalled the hearings on the California delegation until after the convention was underway and until it was clear that a safe majority of delegates were in the Regulars’ camp. As a result, although they were ultimately approved by the committee, the California delegation refused to take their seats in protest and went downstairs to attend the parallel convention of the Communist Labor Party of America convened by NEC members Alfred Wagenknecht and L.E. Katterfeld.

Beesly, Edward Spencer (1831-1915)

Professor of history and political economy at University College, London. A follower of August Comte. Beesly was chairman at the meeting in St. Martin’s Hall, London (September 28, 1864) at which the International Workingmen’s Association was founded. March 1867 he published an article in the Fortnightly Review supporting the activities of the "new model" trade unions.

Begum Roquia (c. 1880-1932)

Begum Roquia, also known as Begum Roquia Sakhawat Hussain, Begum R. S. Hussain or Begum Rokeya, was a pioneer of women’s liberation movement in the South Asian subcontinent.

She was a prolific author, relentless activist for gender equality, and the founder of the Anjuman e Khateen e Islam (Islamic Women’s Association) during the colonial era.

Begum Roquia was born in the Rangpur district of northern Bangladesh during the British occupation of the South Asian subcontinent.

Her family was an aristrocratic Muslim family (Ashraf). The medium of education at home was the combination of both Arabic and Persian languages As per cultural standards of the day, her family was against teaching Bangla which according to them was a tool of preaching ‘Hindu communalism’. But Roquia eventually learned both English and Bangla with the help of her elder brother Ibraheem.

At the age of 16, she married Urdu speaking Khan Bahadur Sakhawat Hussain who was a civil sevant under British administration.

Sakhawat Hussain also was a progressive supporter of the women’s education movement. He encouraged his wife Begum Roquia to begin writing and to accumulate money to use in the founding of a school primarily for Muslim girls.

Begum Roquia set up the Sakhawat Memorial High School in 1909, naming it in tribute of her husband who died earlier the same year.

Begum Roquia wrote extensively on the struggle for women’s rights and education and maintained active involvement in her girls’ school until her death.

She remains a revered and celebrated figure in the history of Bangladesh.

Related link:Wikipedia.

Belani, Jagu Bhatt (1928– present)

Born Princely State of Bhavnagar (Gujarat). Joined Bolshevik Mazdoor Party after WWII. Secretary, West Zone Committee, BMP. Worked in Bhavnagar (Gujarat). Chairman, Anti-Unemployment Committee, Ahmedabad, 1959. Lifelong political activist. Resides in Bharuch East, Gujarat.

Compiled by Charles Wesley Ervin

Bell, Thomas (1882-1944)

Thomas Bell was born in Glasgow in 1882, the son of a stone mason. In 1900 he joined the Independent Labour Party but became dissatisfied with its attitude to trade unions and industrial workers. From the ILP he joined the Marxist Social Democratic Federation. But his continuing views on unions and workers led him, and those who thought like him, to be denounced by SDF leadership as “Impossibilists” and the entire group was expelled at the 1903 SDF conference.

Bell, along with others such as Willie Gallagher and Arthur MacManus, joined the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), which was established in 1903 after their expulsion from the SDF. This organisation was also Marxist but was small; it was an overwhelmingly Scottish grouping, although there were also were small groups in Sheffield and Derby. This British SLP also had close links with the Socialist Labor Party of America led by Daniel de Leon.

Bell soon became one of the SLP’s most prominent members, in the process steering it away from the grip of ‘de Leonism’. The SLP’s journal was called the The Socialist and in 1919 Tom Bell became its editor. Under his editorship, its circulation rose to 8,000 in 1920.

Bell was also one of the leaders of the Clyde Workers’ Committee and shop steward’s movement during the First World War. He was also President of the Scottish Ironmoulders’ and leader of the 1920 moulders’ strike, which was successful in obtaining a wage rise for the whole of the engineering industry. He was also active on trade union affairs in Merseyside and Manchester. Bell was a close associate of James Connolly and was Chairman of Manchester Labour College and Plebs League.

He played an important role in the establishment of the Communist Party in 1920, as one of three SLP delegates (Arthur MacManus and William Paul) to the Communist Unity Committee and Convention. He and his fellow SLP delegates’ support for the establishment of the CPGB led to them being expelled from the SLP.

Bell was a Communist Party Executive member from 1920-1929 and initially National Organiser. During the political show trial of the British Communist Party leadership in 1925, Bell was sentenced under the Incitement to Mutiny Act 1797 to six months in Wandsworth jail, along with Arthur MacManus, J. T. Murphy, J. R. Campbell, Robin Page Arnot, Tom Wintringham, Eric Cant. Five others got sentences of 12 months: Albert Inkpin, Willie Gallagher, Harry Pollitt, William Rust and Wal Hannington. (Bell was in the cell next door to Gallagher in Wandsworth jail).

Despite finding himself a little sidelined by the ‘bolshevisation’ measures of the late 1920s and early 1930s, he remained a member of the Party with some influence until his death in 1944.

From Graham Stevenson.

Further Reading: Thomas Bell Archive.

Bellamy, Edward (1850-1898)

American author, famous for his utopian novel set in the year 2000, Looking Backward, published in 1888.

Born in Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, he attended Union College, but did not graduate; studied law, but left and worked briefly in as a journalist in New York and Massachusetts before devoting himself to literature.

His books include Dr. Heidenhoff’s Process (1880), Miss Ludington’s Sister (1884) and The Duke of Stockbridge. His feeling of injustice in the economic system lead him to write Looking Backward: 2000–1887, which influenced many intellectuals, and Marxist of the day. “Bellamy Clubs” sprang up all over the US to discuss the book’s ideas. A short story The Parable of the Water-Tank from the book Equality (1897), was popular with a number of early American socialists.

Bellamy died at his childhood home in Chicopee Falls at the age of 48 from tuberculosis.

See Utopianism Subject Archive, including Looking Backward from 2000–1887.

Belli, Mihri (1915-...)

The founder of the thesis of "National Democratic Revolution".

He studied economics in the USA. He became there a marxist and joined the African-American and Workers movements. He turned back to Turkey in 1940 and joined the Communist Party of Turkey (TKP). He organised the Union of the Progressive Youth. In 1944 he was arrested and sentenced to prison for two years. In 1946 he went to Greece to join the Greece Civil War as a guerilla. He was wounded and stayed at the hospitals in Bulgaria and Soviet Union. He entered to Turkey in 1950 and arrested, stayed in prison for seven years. After the military putsch in 1960 he wrote some articles at the periodicals "Türk Solu" and "Aydinlik Sosyalist Dergi". He escaped from Turkey after the fascist putsch in 1971 and joined the Palestine Liberation Organisation. After the Amnesty Law in 1974 he returned back to Turkey and founded Labourer Party of Turkey (TEP). After the fascist military putsch in 1980 went to Middle-East again, then to Sweden. Turned back to Turkey in 1992 and joined the Freedom and Solidarity Party (ÖDP).

Belinsky, Vissarion (1811-1848)

Russian literary critic who supported socially critical writers.

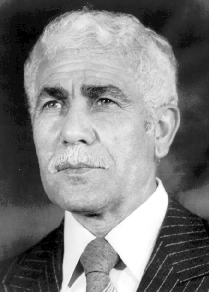

Ben Bella, Ahmed (1916-)

Born in Maghnia, Algeria, in 1916. He served in the French Army during the Second World War. After the war he became involved in the independence movement and in 1949 became leader of Organisation Speciale, the paramilitary wing of the Party of the Algerian People.

Ben Bella was captured in 1952 but he escaped to Egypt where he founded the National Liberation Front (FLN). Under the leadership of Ben Bella the FLN fought a long war of independence from France.

In 1962 Algeria gained its independence and Ben Bella became the country’s first prime minister and in 1963 was elected president. Ben Bella attempted to establish a system similar to the one led by Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt.

However Ben Bella was deposed in 1965 in a military coup led by General Houari Boumedienne and was kept under house arrest until 1979. He spent the next ten years in exile but in 1990 he returned to live in Algeria.

Benjamin, Walter (1892 - 1940)

German Marxist literary critic. Born into a prosperous Jewish family, Benjamin studied philosophy in Berlin, Freiburg, Munich, and Bern. He settled in Berlin in 1920 and worked thereafter as a literary critic and translator. His half-hearted pursuit of an academic career was cut short when the University of Frankfurt rejected his brilliant but unconventional doctoral thesis, The Origin of German Tragic Drama (1928). Benjamin eventually settled in Paris after leaving Germany in 1933 after Hitler came to power. He continued to write essays and reviews for literary journals, but when Paris fell to the Nazis in 1940 he fled south with the hope of escaping to the US via Spain. Informed by the chief of police at the Franco-Spanish border that he would be turned over to the Gestapo, Benjamin committed suicide.

The posthumous publication of Benjamin’s prolific output won him a growing reputation in the later 20th century. The essays containing his philosophical reflections on literature are written in a dense and concentrated style that contains a strong poetic strain. He mixes social criticism and linguistic analysis with historical nostalgia while communicating an underlying sense of pathos and pessimism. The metaphysical quality of his early critical thought gave way to a Marxist inclination in the 1930s. Benjamin’s pronounced intellectual independence and originality are evident in the extended essay Goethe’s Elective Affinities and the essays collected in Illuminations.

The approach to art of the USSR under Stalin was typified, first, by the persecution of all those who expressed any independent thought, and, second, by the adoption of Socialist Realism - the view that art is dedicated to the "realistic" representation of - simplistic, optimistic - "proletarian values" and proletarian life. Subsequent Marxist thinking about art has been largely influenced by Walter Benjamin and Georg Lukács however. Both were exponents of Marxist humanism who saw the important contribution of Marxist theory to aesthetics in the analysis of the condition of labour and in the critique of the alienated and "reified" consciousness of man under capitalism. Benjamin’s collection of essays The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1936) attempts to describe the changed experience of art in the modern world and sees the rise of Fascism and mass society as the culmination of a process of debasement, whereby art ceases to be a means of instruction and becomes instead a mere gratification, a matter of taste alone. "Communism responds by politicising art" - that is, by making art into the instrument by which the false consciousness of the mass man is to be overthrown.

See the Walter Benjamin Archive.

Benjedid, Chadli (1929- )

President of Algeria (1979-92), born in Sebaa. He joined the National Liberation Front shortly after the Algerian revolution began in 1954 and rose through the ranks of the guerrilla forces; by the early 1960s he was on the staff of Colonel (later president) Houari Boumedienne, and he played a decisive role in the latter’s overthrow of President Ahmed Ben Bella in 1965. Subsequently serving in the Revolutionary Council and as acting minister of defense (1978), he was elected president in February 1979 and reelected in 1984 and 1988. When his democratization program threatened to bring Muslim fundamentalists to power, he was forced to resign in January 1992 by a military-dominated junta.

Bentham, Jeremy (1748-1832)

Idealist. Writer on law and ethics; a barrister from 1772. Made a study of the theory of law and developed the idea that laws should be socially beneficial and not merely a reflection of the status quo. Popularised the Utilitarian theory that all actions are right when they promote the ’greatest happiness of the greatest number’. In 1808 he met James Mill and with him formed a group that propagated Utilitarian ideas among the radical bourgeoisie and intellectuals.

Berger, Victor Louis (Luitpold) (1860—1929)

Founding member of the Socialist Party of America and an important and influential Socialist journalist who helped establish the so-called Sewer Socialist movement. The first Socialist elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, in 1919 he was convicted of violating the Espionage Act for his anti-militarist views and as a result was twice denied the seat to which he had been elected in the House of Representatives.

Founding member of the Socialist Party of America and an important and influential Socialist journalist who helped establish the so-called Sewer Socialist movement. The first Socialist elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, in 1919 he was convicted of violating the Espionage Act for his anti-militarist views and as a result was twice denied the seat to which he had been elected in the House of Representatives.

Early years

Born to a Jewish family in Nieder Rehbach, Austria-Hungary (now in Romania) on February 28, 1860, Victor L. Berger attended the Gymnasium at Leutschau (today in Slovakia) and the universities at Budapest and Vienna. He emigrated to the United States in 1878 with his parents, settling near Bridgeport, Connecticut. From there he moved to Woodstock, Illinois in 1880, and then to Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 1881, where he was a schoolteacher and newspaper editor.

Berger was credited by trade union leader Eugene V. Debs for having won him over to the cause of socialism. Jailed for six months for violating a federal anti-strike injunction in the 1894 strike of the American Railway Union, Debs turned to reading:

"Books and pamphlets and letters from socialists came by every mail and I began to read and think and dissect the anatomy of the system in which workingmen, however organized, could be shattered and battered and splintered on a single stroke....

"It was at this time, when the first glimmerings of socialism were beginning to penetrate, that Victor L. Berger — and I have loved him ever since — came to Woodstock [jail], as if a providential instrument, and delivered the first impassioned message of socialism I had ever heard — the very first to set the wires humming in my system. As a souvenir of that visit there is in my library a volume of Capital by Karl Marx, inscribed with the compliments of Victor L. Berger, which I cherish as a token of priceless value."

In 1896 Berger was a delegate to the People’s Party Convention in St. Louis.

In 1897 he married a former student, Meta Schlichting. The couple raised two daughters, Doris and Elsa, who at first spoke only German in the home, indicative of their parents' cultural orientation. Berger was short and stocky, with a studious demeanor, and had both a self-deprecating sense of humor and a volatile temper. Although loyal to friends, he was strongly opinionated and intolerant of dissenting views. His ideological sparring partner and comrade Morris Hillquit later recalled of Berger that

"He was sublimely egotistical, but somehow his egotism did not smack of conceit and was not offensive. It was the expression of deep and naive faith in himself, and this unshakable faith was one of the mainsprings of his power over men.".

Berger was a founding member of the Social Democracy of America in 1897 and led the split of the "political action" faction of that organization to form the Social Democratic Party of America (SDP) in 1898. He was a member of the governing National Executive Committee of the SDP for its entire duration.

Berger was a founder of the Socialist Party of America in 1901 and played a critical role in the negotiations with an east coast dissident faction of the Socialist Labor Party in the establishment of this new political party. Berger was regarded as one of the party's leading revisionist Marxists, an advocate of the trade union-oriented and incremental politics of Edward Bernstein. He advocated the use of electoral politics to implement reforms and thus gradually build a collectivist society.

Berger was a man of the written word and back room negotiation, not a notable public speaker. He retained a heavy German accent and had a voice which did not project well. As a rule he did not accept outdoor speaking engagements and was a poor campaigner, preferring one-on-one relationships to mass oratory.Berger was, however, a newspaper editorialist par excellence. Throughout his life he published and edited a number of different papers, including the German language Vorwärts ("Forward") (1892-1911), the Social-Democratic Herald (1901-1913), and the Milwaukee Leader (1911-1929). His papers were tied to the socialist movement and organized labor through the Milwaukee Federated Trades Council.

First term in Congress

Berger ran for Congress and lost in 1904 before winning Wisconsin's 5th congressional district seat in 1910 as the first Socialist to serve in the United States Congress. In Congress, he focused on issues related to the District of Columbia and also more radical proposals, including eliminating the President's veto, abolishing the Senate, and the social takeover of major industries. Berger gained national publicity for his old-age pension bill, the first of its kind introduced into Congress. Although he did not win re-election in 1912, 1914 or 1916, he remained active in Wisconsin and Socialist Party politics.

Berger was very active in the biggest party controversy of the pre-war years, the fight between the SP's center-right "regular" bloc against the syndicalist left wing over the issue of "sabotage." The bitter battle erupted in full force at the 1912 National Convention of the Socialist Party, to which Berger was again a delegate. At issue was language to be inserted into the party constitution which called for the expulsion of "any member of the party who opposes political action or advocates crime, sabotage, or other methods of violence as a weapon of the working class to aid in its emancipation." The debate was vitriolic, with Berger, somewhat unsurprisingly, stating the matter in its most bellicose form:

Comrades, the trouble with our party is that we have men in our councils who claim to be in favor of political action when they are not. We have a number of men who use our political organization — our Socialist Party — as a cloak for what they call direct action, for IWW-ism, sabotage and syndicalism. It is anarchism by a new name....

Comrades, I have gone through a number of splits in this party. It was not always a fight against anarchism in the past. In the past we often had to fight utopianism and fanaticism. Now it is anarchism again that is eating away at the vitals of our party.

If there is to be a parting of the ways, if there is to be a split — and it seems that you will have it, and must have it — then, I am ready to split right here. I am ready to go back to Milwaukee and appeal to the Socialists all over the country to cut this cancer out of our organization."

The regulars won the day handily at the Indianapolis convention of 1912, with a successful recall of IWW leader "Big Bill" Haywood from the SP's National Executive Committee and an exodus of disaffected left wingers following shortly thereafter. The remaining radicals in the party remembered bitterly Berger's role in this affair and the ill feelings continued to fester until erupting anew at the end of the decade.

Berger and World War I

Berger's views on World War I were complicated by the Socialist view and the difficulties surrounding his German heritage. However, he did support his party's stance against the war. When the United States entered the war and passed the Espionage Act in 1917, Berger's continued opposition made him a target. He and four other Socialists were indicted under the Espionage Act in February 1918; the trial followed on December 9 of that year, and on February 20, 1919, Berger was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in federal prison. The trial was presided over by Judge Kenesaw Landis, who later became the first commissioner of Major League Baseball. His conviction was appealed, and ultimately overturned by the Supreme Court on January 31, 1921, which found that Judge Landis had improperly presided over the case after the filing of an affidavit of prejudice.

In spite of his being under indictment at the time, the voters of Milwaukee elected Berger to the House of Representatives in 1918. When he arrived in Washington to claim his seat, Congress formed a special committee to determine whether a convicted felon and war opponent should be seated as a member of Congress. On November 10, 1919 they concluded that he should not, and declared the seat vacant. Wisconsin promptly held a special election to fill the vacant seat, and on December 19, 1919, elected Berger a second time. On January 10, 1920, the House again refused to seat him, and the seat remained vacant until 1921, when Republican William H. Stafford claimed the seat after defeating Berger in the 1920 general election. Second stint in Congress

Berger defeated Stafford in 1922 and was reelected in 1924 and 1926. In those terms, he dealt with Constitutional changes, a proposed old-age pension, unemployment insurance, and public housing. He also supported the diplomatic recognition of the Soviet Union and the revision of the Treaty of Versailles. After his defeat by Stafford in 1928, he returned to Milwaukee and resumed his career as a newspaper editor.

On July 16, 1929 Berger was struck by a streetcar at the corner of 3rd and Clarke Streets in Milwaukee. The accident fractured his skull, and he died of his injuries on August 7, 1929. Prior to burial at Forest Home Cemetery his body lay in state at City Hall and was viewed by 75,000 citizens of the city.

Writings

Victor Berger's journalism was voluminous, but rarely reproduced in book or pamphlet form. A massive number of editorials were produced for the pages of the paper he edited, the Milwaukee Leader. In addition, two books collecting Berger's writings were published, Berger's Broadsides (1912), and Voice and Pen of Victor L. Berger: Congressional Speeches and Editorials (1929). Victor Berger's papers are housed at the Wisconsin Historical Society, as is the complete run of the Milwaukee Leader on microfilm.

Beria, Lavrenti (1899-1953)

Georgian. Organised Bolshevik group in Baku in 1917; 1921-31 directed GPU in Georgia. First Sec. Georgian CP from 1931; leader of NKVD from 1938 until Stalin’s death. Responsible for countless murders on his own initiative as well as on Stalin’s orders; summarily shot shortly after Stalin’s death.

Berkeley, George (1685 - 1753)

Bishop Berkeley came to the defence of religion against Locke’s Empiricism, but did so by turning the empiricist theory "against itself".

“It is evident to anyone who takes a survey of the objects of human knowledge, that they are either ideas actually imprinted on the senses; or else such as are perceived by attending to the passions and operations of the mind; or lastly, ideas formed by the help of memory or imagination ... That neither our thoughts nor passions nor ideas forms by the imagination exist without mind is what everybody will allow ... and to me it seems no less evident that the various sensations or ideas imprinted on the senses, however blended or combined together cannot exist otherwise than in a mind perceiving them”.

“It is indeed an opinion strangely prevailing among men that houses, mountains, rivers and in a word, all sensible objects, have an existence, natural or real, distinct from their being perceived by the understanding ... For what are the aforementioned objects but the things we perceive by sense? And what do we perceive besides our own ideas or sensations? And is it plainly repugnant that anyone of these, or any combination of them, should exist unperceived”. [from Of the Principles of Human Understanding]

In other words, he said to the empiricists: ‘You know that sensations exist, but you know not of anything beyond; you are acting only upon senses’. Berkeley proved that empiricism leads to subjective idealism. In order to explain the existence of knowledge at all, Berkeley invented a special new sense which is able to sense "notions", thus leading back to religion.

Berkeley’s subjective idealist attack on materialism, purporting to show that the assertion that something exists outside the mind of the individual human being is absurd, useless and unprovable, was in fact a great service to the development of materialism. This can be said because Berkeley drew to its "logical conclusion" the development of empiricism.

Bacon asserted, as a materialist, that we had to use our eyes, ears and hands and go out to Nature to discover truth. Hobbes and Locke developed Bacon’s "empiricism" in the narrow sense, by reducing the investigation of Nature to experience to sense perception, equating sense perception with ideas, and ultimately equating the rational faculty as a whole with the action of the external world on the senses, with sense perception.

Berkeley shows that this line of development leads to knowledge only of phenomena, in the form of sensations, not the essence of things existing outside of and independently of our perception of us. Perception has become, not people’s connection with Nature, but a barrier sealing us off from Nature absolutely. The logical conclusion of empiricism is subjective idealism.

Berkeley avoids outright "solipsism" by adding to his thesis, that the God can perceive sensations independently of us, thus allowing "things" to exist while we are not actually looking at them. This unconvincing objective idealist "correction" to his otherwise consistent subjective idealism grew more significant in the course of his development.

Nevertheless, Berkeley’s insane conclusions are generally accepted as the last word on the question of matter for the French, British and Maerican traditions of idealist philosophy for a long time afterwards.

In order to develop further, materialism had to find an answer to Berkeley’s challenge.

Berman, Marshall (1940- 11th September 2013)

Completed his Ph.D. at Harvard in 1968. Currently Professor of Political Science at CUNY, teaching Political Philosophy and Urbanism and is on the editorial board of Dissent and is a regular contributor to The Nation, The New York Times Book Review, Bennington Review, New Left Review, New Politics and the Village Voice Literary Supplement. His main works are The Politics of Authenticity, All That is Solid Melts in Air, One Hundred Years of Spectacle and Adventures in Marxism. In Adventures in Marxism Berman tells of how while a student at Columbia University in 1959, the chance discovery of the 1844 Manuscripts proved a revelation and inspiration, and became the foundation for all his future work.

Bernal J D (John Desmond Bernal) (1901-1971)

Irish-born scientist and communist.

He was educated at Bedford School and Emmanuel College, Cambridge, where he studied both mathematics and science for a B. A. degree in 1922; which he followed by another year of natural sciences. He taught himself the theory of space groups, including the quaternion method; this became the mathematical basis of later work on crystal structure. After graduating he started research under Sir William Bragg at the Davy-Faraday Laboratory in London. In 1924 he determined the structure of graphite.

He joined the Communist Party in 1923, but left in 1933. In 1939, he published The Social Function of Science, probably the earliest text on the sociology of science. He was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize in 1953.

He is known also as joint inventor of the Mulberry Harbour. After helping orchestrate D-Day, he landed on Normandy the day after D-Day. He is also famous for having firstly proposed in 1929 the so-called Bernal sphere, a type of space habitat intended as a long-term home for permanent residents.

See J D Bernal Archive.

Bernstein, Edward (1850-1932)

German Social Democrat; left Germany during the anti-Socialist laws and edited Sozial Demokrat in Switzerland. Expelled from there in 1888, where he lived in London till 1900. He was a friend of Engels in Engels’ last years and was named his literary executor. Reichstag Deputy 1902-1906, 1912-1918, 1920-1928. A pacifist-centrist during World War I. Founder of the Independent Social Democratic Party (USID) 1916, but returned to the Social Democractic Party in 1919. Chief exponent of revisionism and reformism for over twenty five years, beginning 1896. Editor and author of Evolutionary Socialism, 1899 among other works. In this work he developed a theory of the gradual transformation of capitalism into socialism; coined the famous aphorism: "The movement is everything, the final goal nothing"; believing that revolution was not necessary.

See the Eduard Bernstein Archive.

Berzin, Ian Karlovich (1889-1938)

A.k.a. Jānis Bērziņš, Latvian and Soviet communist military official and politician.

The future Ian (pronounced “Yan”) Berzin was born Pēteris Ķuzis on 13 November 1889 (n.s.) to a Courland Latvian peasant family.[1] He worked as a teacher and joined the Latvian Social Democratic Workers Party in 1902.[2] Berzin was a participant in the Russian Revolution of 1905 and came to be a dedicated supporter of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Workers Party (RSDWP), chosen as Secretary of the Petersburg Committee of the RSDWP in 1906.[3] In Latvia following the failed 1905 uprising, Berzin was a leading organizer of the Bolshevik faction within the Latvian Social Democratic Workers Party and led the fight against the Menshevik dominated Central Committee of that organization.[4]

In 1914, Berzin was elected Editor in Chief of Cina (“Struggle”), the official organ of the Latvian Social Democratic Workers Party. He was a representative of that party to the Zimmerwald Conference of 1915 and was a member of the vigorously antimilitarist and revolutionary Zimmerwald Left minority group headed by Lenin at that gathering.[5] In 1916, Berzin lived in the United States, where he participated in the socialist movement and wrote for its press.[6] He returned home to Europe during the summer of 1917, following the revolution of March 1917.

Berzin was elected a member of the Central Committee of the RSDWP at its 6th Congress in 1917 and an alternate member at the 7th Congress in the following year. He was later named as Soviet Russia’s ambassador to Switzerland, where he remained until the expulsion of Soviet embassy personnel after civil unrest in November 1918.[7] Berzin was named as People’s Commissar of Enlightenment (Minister of Education) of Soviet Latvia in the short-lived Soviet Latvian Republic of early 1919.[8]

According to the controversial historian Victor Suvorov, Berzin was a principle organizer of Lenin’s Red Terror during the Russian Civil War, credited with devising the system of taking and shooting hostages[9] to recover deserters and to put down peasant rebellions in areas controlled by the Red Army. Suvorov also intimates that Berzin was recognized by his superiors for his work in suppressing Russian sailors involved in the Kronstadt rebellion in March 1921.[10]

Berzin briefly served as Secretary of the Communist International during 1919-1920, one of the chief functionaries involved in its day to day operations.[11] He was taken from the Comintern apparatus to work in the “Registration Department” (Military Intelligence) of the Red Army’s General Staff in December 1920.[12] Berzin was named as Soviet Ambassador to Finland in 1921,[13] and subsequently remained in the diplomatic service as a deputy plenipotentiary in London and as Soviet Ambassador to Austria from 1925 to 1927.[14][15] Berzin was at the same time deputy chief of Military Intelligence from December 27, 1921 through March of 1924, at which time he was promoted to chief of that department.[16] In 1929 Berzin was recalled to Moscow and removed from the diplomatic corps, ostensibly to be placed in charge of the Soviet government’s central archives and made editor-in-chief of the historical magazine Krasnyi Arkhiv (“Red Archives”).[17] Berzin continued his work as chief of the Red Army’s Fourth Bureau (military intelligence), the GRU.[18]Among his agents was Richard Sorge.[19]

Berzin seems to have been removed from his position as chief of military intelligence in the spring of 1935. From April 1935 through June 1936, Berzin served as deputy commander of the army in the Soviet Far East.[20] During 1936 and 1937, he was chief military advisor to the Republican forces in the Spanish Civil War[21] under the nom de guerre Grishin.

In June of 1937, Berzin was recalled from Spain and reappointed as head of Military Intelligence.[22] This second stint at the head of GRU came to an abrupt end with Berzin’s arrest on May 13, 1938 during the secret police terror of 1937-38. On 29 July 1938 he was shot in the cellars of the Lubyanka headquarters in Moscow.[23] Interestingly, it seems that Berzin’s downfall came in connection with a secret police case having nothing to do with Berzin’s work in the diplomatic service or military intelligence, but rather a so-called “Case of the espionage organization in the Central Archival Administration."[24]

Berzin was posthumously rehabilitated following the death of Joseph Stalin.

Footnotes

1. Branko Lazitch and Milorad M. Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern: New, Revised, and Expanded Edition. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1986; pg. 27. Lazitch and Drachkovitch give the apparently erroneous patronymic “Antonovich” for Berzin, it should be noted. One does see this name or initial in other sources; see, for example: V.A. Torchinov and A.M. Leontiuk, Vokrug Stalina: Istoriko-biograficheskii spravochnik. St. Petersburg: Filologicheskii fakul’tet Sankt-Peterburgskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, 2000. Reference to Berzin’s peasant origins is also made by George Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police. Oxford: Oxford University Press/Clarendon Press, 1981; pg. 301.

2. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27; G.M. Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) – VKP(b) i Komintern: 1919-1943 dokumenty. Moscow: ROSSPEN, 2004; pg. 830.

3. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27

4. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27.

5. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27.

6. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27.

7. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27.

8. Torchinov and Leontiuk, Vokrug Stalina: Istoriko-biograficheskii spravochnik, pg. 84. Note that Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police, pg. 301, has Berzin as deputy People’s Commissar of Internal Affairs during this interlude.

9. Viktor Suvorov, Inside Soviet Military Intelligence. New York: Macmillan, 1984.

10. Suvorov Inside Soviet Military Intelligence, New York: Macmillan, 1984.

11. Torchinov and Leontiuk, Vokrug Stalina: Istoriko-biograficheskii spravochnik, pg. 84.

12. Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police, pg. 301. G.M. Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) – VKP(b) i Komintern, pg. 830.

13. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27.

14. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27.

15. Torchinov and Leontiuk, Vokrug Stalina: Istoriko-biograficheskii spravochnik, pg. 84.

16. Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police, pg. 301.

17. Lazitch and Drachkovitch, Biographical Dictionary of the Comintern, pg. 27.

18. Suvorov, Viktor, Inside Soviet Military Intelligence, New York: Macmillan, 1984. G.M. Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) – VKP(b) i Komintern, pg. 830. Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police, pg. 301.

19. Agent: Sorge, Richard

20. G.M. Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) – VKP(b) i Komintern, pg. 830.

21. G.M. Adibekov et al. (eds.), Politbiuro TsK RKP(b) – VKP(b) i Komintern, pg. 830.

22. Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police, pg. 301.

23. David J. Nordlander, “Origins of a Gulag Capital: Magadan and Stalinist Control in the Early 1930s,” Slavic Review, Vol. 57, No. 4 (Winter, 1998), pp. 791-812

24. Torchinov and Leontiuk, Vokrug Stalina: Istoriko-biograficheskii spravochnik, pg. 84. The exact words in this book are: “Ia.A. Berzin byl rasstrelian po ‘delu o shpionskoi organizatsiia v Tsentral’nom arkhivnom upravlenii (TsAU) SSSR.’”

Additional Reading

Gorchakov, Ovidii Aleksandrovich, Ian Berzin – komandarm GRU. St. Petersburg: Izdatel’skii dom “Neva,” 2004.