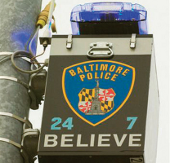

Blue-light Baltimore

Anyone taking the south-bound night train into Baltimore glimpses a memorable vista as the train comes into the city, passing blocks of boarded up row houses and desolate streets on the city’s working class east side. Stretching across the horizon as far as the eye can see is an arc of flashing blue lights, like those on a police car. The lights are portable police cameras mounted on lamp posts throughout the inner city, designed to dissuade drug dealing. But as everyone knows, in reality it’s just a charade of cat-and -mouse, pushing the dealing a few blocks off before it returns once the cameras shift again; a charade that has gone on for years now with no discernible effect. “Blue light Baltimore” is more than a metaphor, however; it’s a lived reality for much of the city and a sign of the depth of social crisis already embedded here before the collapse of the 2008 spun into recession without end.

Baltimore was one of the hardest hit cities in the early days of the subprime mortgage crisis, a situation well captured in the documentary American Casino. Predatory lending by national banks like Wells Fargo in neighborhoods such as Belair-Edison and Sandtown pushed up to one third of housing in some stage of foreclosure, a situation that caused the city in a failed attempt to sue Wells Fargo for intentionally targeting minority neighborhoods. But except for a few abortive attempts in the early stage of the housing market crisis by the now-defunct ACORN (Associated Communities Organized for Reform Now) to symbolically occupy houses, few protested. Instead, people internalized foreclosure as personal failure and private shame.

I remember attending a conference a couple years ago put on by mainstream community groups working on foreclosure issues. Social workers and organizers were puzzled why, despite intense outreach efforts, no one was coming in for help. One organizer spoke about foreclosure avoidance services at a local church and afterwards the minister came up and whispered to her privately how his family was being foreclosed. But—and this is key—he was too ashamed to mention it publicly in front of his congregation. As a result of this collective denial, people moved out at night without saying anything to neighbors, thereby avoiding the humiliation of public eviction when the Sheriff came. In American Casino few interviewed losing their home to foreclosure, even those who were most conscious of how they were being screwed over by banks, saw their private suffering as a collective problem open to collective action. While people understood all too well the systemic roots and injustices behind their personal tragedies, most could in the end only envision personal solutions as the way out.

Holding On and Making Do

Up until now, this resort to personal solutions has been the main response to the current crisis here. Many of the survival strategies pointed out in the Insurgent Notes article by Henri Simon in issue #1 are the new norm—or extensions of old survival techniques. Others can be added, such as income maximizing strategies providing under the table services that indirectly depend on tapping state funding, such as setting up informal day care centers and assisted living homes for welfare and Social Security check recipients. Skilled trade workers such as roofers, carpenters, and electricians secretly do side jobs at lower prices on company time using company tools and equipment for inner-city working class households; a case of workers not only recuperating their labor power but also a situation where what on the surface looks likes individual survival also demonstrates an underlying sense of collective solidarity with others. When I asked an acquaintance, a 57-year-old Black drywall worker who was forced to move back to a trailer in rural Virginia, partly because of personal problems and partly because of the collapse of the construction industry, how he survived, he wrote back:

Thank God, my home and acreage has been paid off for years so I only have to pay personal property taxes. I did grow weed the first two years that I was back home but I broke the addiction to dealing because of fear of being detected by the younger violent dealers and rip off boys. People who knew me in my younger years started becomlng suspicious of me doing something since there was no construction going on. I live (very) simple because my savings have dropped drastically. I sold my Home Depot, Diebold, AFLAC and Exxon stock in that order. I mistakenly thought that I was going to get some drywall contracts somewhere with the many contacts that I have in different states. I did not think that it was going to get this bad. I hide funds so that I can qualify for food stamps and fuel assistance. I have had some drywall work since I have been home and I used to return to the D.C. area often to do work for clients that have known me for years.

In a city like Baltimore where the drug trade is a major employer of last resort, it’s impossible to accurately gauge what role this sector plays in providing or supplementing income for many people unable to get jobs or earn adequate income in the formal economy. The visible drug markets on the corners, the targets of the “blue lights,” are just the tip of a larger iceberg that extends underneath, influencing and conditioning (mostly negatively) facets of social life, everyday interactions and extension of trust. Besides the direct distributing and street corner drug sales, the drug economy generates secondary and tertiary ripple effects on the local economy and individual income strategies too. A woman I used to give rides to after school, a former heroin addict, cut off social services but still getting Medicaid, used legally obtained Oxycontin to barter child care services from neighbors and friends. Another woman I used to work with set up a hair salon on weekends in her basement to cut drug dealers’ hair, saying she made more money in a few hours than she did all week working.

This reliance on various individual survival strategies, shifting between legal or “illegal” depending on circumstances, is not an example of “false consciousness” or backwardness but has to be placed in context, namely the fragmentation and isolation stemming from the last several decades of declining sociality, itself a result of shifting changes in the economy, with the resulting effects on personal life and patterns of consumption.

The Decline of the Social

Traditional collective institutions in Baltimore, from unions to community organizations, have faded over the past several decades. A poignant example of this decline can be seen in the practice of local construction unions in the Baltimore area now being forced to hire paid picketers to staff picket lines, so incapable are these organizations of generating any genuine interest or participation from their own members. The sit-down corner bar, once a mainstay of working class neighborhoods, gets converted into the plexiglass-protected carry-out, where what little interaction goes on now takes place behind shielded glass and iron grates. Entertainment is brought into the home through cable television with its hundreds of channels and not something you go out to socialize with others for. The need to work multiple jobs drastically cuts down on free time. The result of these and many other trends is an individuation and atomization in working class Baltimore that has largely eroded and undercut a sense of larger collective identity and participation.

But if in a very primitive sense the aforementioned individual survival strategies carried out in such conditions show some germ for a larger potential collective response, holding out distant hopes for a better future, the depth and speed of the current crisis is pushing more people into crisis themselves. Survival strategies meant as temporary stop-gaps until an economic rebound will be tested and eventually exhausted as the economic crisis not only continues, but deteriorates with no foreseeable end—except for repeated demands for austerity and declines in living standards. Unless, of course, there is a qualitative and quantitative change in resistance.

Another real possibility, not necessarily contradicting the first, is the further entrenchment of drug distribution networks in the inner city as the fiscal crisis of the local state forces cutbacks in public services and the state presence shrinks except for its police presence. As an example of what such a future may bring, in a case reminiscent of Naples or Ciudad Juarez, last year Baltimore authorities busted one such network, the well-organized Black Guerilla Family, that had managed to infiltrate street-level anti-gang and violence mediation programs and through a front group even produced a pamphlet written by its leader calling for entrepreneurism and community “self-help” which was endorsed, to their later embarrassment, by several local politicians.

Thus coming to grips with the impact of Occupy Baltimore means not just evaluating what the movement has been able to do or not do on its own terms but rooting its experiences in this larger picture of class decomposition and re-composition that in Baltimore followed in the wake of the same patterns of deindustrialization, suburban flight and disinvestment gutting other former manufacturing cities like Detroit, St. Louis, and Cleveland.

Thus coming to grips with the impact of Occupy Baltimore means not just evaluating what the movement has been able to do or not do on its own terms but rooting its experiences in this larger picture of class decomposition and re-composition that in Baltimore followed in the wake of the same patterns of deindustrialization, suburban flight and disinvestment gutting other former manufacturing cities like Detroit, St. Louis, and Cleveland.

Occupy Baltimore’s Impact

I can’t speak about the internal workings of Occupy Baltimore because I didn’t get down to the site to form my own impressions before it was peacefully shut down by the city in mid-December. Instead I will discuss what I think has been Occupy’s larger effect on the city, with its strengths and weaknesses.

From the beginning, Occupy here was able to draw on existing activist networks around Red Emma’s bookstore and café. This meant from the start that Occupy benefited from previous networking and informal organization and didn’t have to constitute them from scratch, as was the case in other cities. Occupy Baltimore also profited from a hands-off strategy by the police and city administration, which when combined with the tactical savvy of local organizers, meant that Occupy successfully avoided the confrontations like those playing out in Oakland, Denver and elsewhere.

Occupy Baltimore also basked in mostly sympathetic media coverage. True, there were a few negative stories, mainly relating to alleged crimes committed by some of the fringe elements who gravitated to the camp during its high point. And predictably, the local Fox affiliate tried to set up an expose discovering drug paraphernalia in tents. But these were exceptions to the rule. Surprisingly, the local daily, the Baltimore Sun, printed an Occupy Baltimore guest op-ed, a consideration this paper rarely extends to any remotely similar point of view. To a large extent, this sympathy came because Occupy Baltimore like elsewhere drew disproportionate support from under- and unemployed young members of the local “Creative Class”: art students, web programmers, media workers, musicians, downtown hipster marginals and bohemians, etc., white, well-educated and articulate.

At the same time, Occupy Baltimore managed to get significant mainstream union endorsements and support. Unions such as SEIU suddenly adopted the Occupy slogan in leaflets. On October 26th, heads of 13 city union locals, including the Fraternal Order of Police, sent an open letter to Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake calling for the Mayor to “stand down” and not remove but continue to dialogue with protesters. The Maryland/DC AFL-CIO followed up in late November with a support Occupy resolution calling for the Mayors of both cities not to evict Occupy camps. While undoubtedly much of this support came from a calculated desire not to be caught off-guard and left behind by a movement that threatened to turn into a mass outpouring of anger against the banks and income inequality and escape control by traditional organizations such as the unions and Democratic Party, in the context of the sclerotic and ossified standards of local labor union practices, these were significant steps, even though the resolutions had no teeth in them and thus were for all practical purposes, posturing and positioning.

Another tangible victory for Occupy Baltimore came with the open meeting of an alternative economic development committee involving Occupy with the Baltimore Development Corporation (BDC). The BDC is a shadowy public-private business partnership funded in part with public funds from local taxes that is exempt from sunshine laws requiring open meetings; the BDC has always resisted outside scrutiny. The fact that the head of the BDC felt compelled to meet with the Another Baltimore Development Committee is Possible and Occupy in a highly orchestrated meeting on the steps of the BDC offices to open “dialogue” demonstrates once again on one hand the fear that the Occupy movement would overstep the usual channels of containment and on the other hand the desire for the local city administration and other similar players to “ride the tiger,” i.e., continue symbolic ritual “dialogue” until the movement winds down and is no longer considered a threat.

But more important than how the union leadership responded is the effect Occupy has had on ordinary union members and other workers. For example, at a two month Occupy Baltimore evaluation meeting I attended in mid-December, which attracted close to 200 people, mostly new to politics, a UNITE organizer speaking from the floor said how “energized” union members became whenever they visited the Occupy camp. It’s impossible to know how much of this cross pollination has taken place. Although affecting relatively few people, this new permeability between the previously separated, countering fragmentation and sharing experiences and dialogue despite all of Occupy’s significant limitations, still has opened up possibilities not seen here for many years. A process that has probably been repeated to one extent or another in the hundreds of Occupy sites around the country. It won’t be enough in itself to shake off the decades-long narrative of defeat but it’s a promising start.

Related articles

- The Countrywide Settlement in Context: Discrimination and the Subprime Mortgage Meltdown (beaconbroadside.com)

- Southwest Baltimore School On Alert After Scarlet Fever Outbreak (baltimore.cbslocal.com)