Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Underground press

|

| This article includes a list of references, related reading or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please improve this article by introducing more precise citations where appropriate. (June 2008) |

The phrase underground press is most often used to refer to the independently published and distributed underground papers associated with the counterculture of the late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States, Canada, United Kingdom, and other western nations. It also refers to illegal publications under oppressive governments, for example, the samizdat and bibuÅa in the Soviet Union and Poland respectively.

Contents |

This movement borrowed the name from previous underground presses such as the Dutch underground press during the Nazi occupations of the 1940s. The French resistance also published an underground press and prisoners of war (POWs) published an underground newspaper called Pow wow. In Eastern Europe, also since approximately the 1940, underground publications were known by the name samizdat. Those predecessors were truly "underground," meaning they were illegal, thus published and distributed covertly. While the countercultural "underground" papers frequently battled with governmental authorities, for the most part they were distributed openly through a network of street vendors, newsstands and head shops, and thus reached a wide audience.

The underground press in the 1960s and '70s existed in most countries with high GDP per capita and freedom of the press; similar publications existed in some developing countries and as part of the samizdat movement in the communist states, notably Czechoslovakia. Published as weeklies, monthlies, or "occasionals", and usually associated with left-wing politics, they evolved on the one hand into today's alternative weeklies and on the other into zines.

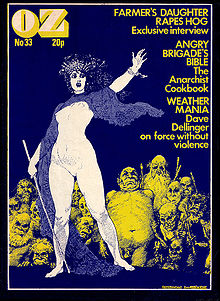

The most prominent underground publication in Australia was a satirical magazine called Oz (1963 to 1969), which owed an obvious debt to the UK magazine Private Eye. The original Australian edition appeared in 1963 and it continued sporadically until 1969. The Australian editions published after 1966 were edited by Richard Walsh, following the departure for the UK of his original co-editors Richard Neville and Martin Sharp, who founded the British edition ("London Oz") in 1967.

In London, Barry Miles, John Hopkins and others produced International Times which, following legal threats from The Times newspaper was renamed IT.

Richard Neville arrived in London from Australia where he had edited Oz (1963 to 1969). He launched a British version (1967 to 1973), which was A4 (as opposed to IT's broadsheet format). Very quickly, the relaunched Oz shed its more austere satire magazine image and became a mouthpiece of the Underground. It was the most colourful and visually adventurous of the alternative press (sometimes to the point of near-illegibility), with designers like Martin Sharp. Other publications followed, such as Friends (later Frendz), based in the Ladbroke Grove area of London, Ink, which was more overtly political, and Gandalf's Garden which espoused the mystic path.

Neville published an account of the counterculture called Playpower, in which he described most of the world's underground publications. He also listed many of the regular key topics from those publications including Vietnam, Black Power, Politics, Police Brutality, Hippies & Lifestyle Revolution, Drugs, Popular Music, New Society, Cinema, Theatre, Graphics, Cartoons etc.

The underground press offered a platform to the socially impotent and mirrored the changing way of life in the UK underground.

Police harassment of the British underground in general became commonplace, to the point that in 1967 the police seemed to focus in particular on the apparent source of agitation: the underground press. The police campaign may have had an effect contrary, however, to that which was presumably intended. If anything, according to one or two who were there at the time, it actually made the underground press stronger. "It focused attention, stiffened resolve, and tended to confirm that what we were doing was considered dangerous to the establishment", remembered Mick Farren. [1] From April 1967, and for some while later, the police raided the offices of International Times to try, it was alleged, to force the paper out of business. In order to raise money for IT a benefit event was put together, "The 14 Hour Technicolor Dream" Alexandra Palace on 29 April, 1967.

On one occasion - in the wake of yet another raid on IT - London's alternative press, somewhat astonishingly, succeeded in pulling off what was billed as a 'reprisal attack' on the police. The paper Black Dwarf published a detailed floor-by-floor 'Guide to Scotland Yard,' complete with diagrams, descriptions of locks on particular doors, and snippets of overheard conversation. The anonymous author, or 'blue dwarf,' as he styled himself,' claimed to have perused archive files, and even to have sampled one or two brands of scotch in the Commissioner's office. The London Evening Standard headlined the incident as "Raid on the Yard". A day or two later The Daily Telegraph announced that the prank had resulted in all security passes to the police headquarters having to be withdrawn and then re-issued.

By the end of the decade, community artists and bands such as Pink Floyd, (before they "went commercial"), the The Deviants, Pink Fairies, Hawkwind, Michael Moorcock and Steve Peregrin Took would arise in a symbiotic co-operation with the underground press. The underground press publicised these bands and this made it possible for them to tour and get record deals. The band members travelled around spreading the ethos and the demand for the newspapers and magazines grew and flourished for a while.

The flaunting of sexuality within the underground press provoked prosecution. IT was taken to court for publishing small ads for homosexuals; despite the 1967 legalisation of homosexuality between consenting adults in private importuning remained subject to prosecution. The Oz "School Kids" issue, brought charges against the three Oz editors who were convicted and given jail sentences. This was the first time the Obscene Publications Act 1959 was combined with a moral conspiracy charge. The convictions were, however, overturned on appeal.

In the United States, the term underground did not mean illegal as it would in other countries. The First Amendment and various court decisions (e.g. Near v. Minnesota) give very broad rights to anyone to publish a newspaper or other publication, and severely restrict the government in any effort to close down or censor a private publication. In fact, when censorship attempts are made by government agencies, they are either done in clandestine fashion (to keep it from being known the action is being taken by a government agency) or are usually ordered stopped by the courts when judicial action is taken in response to them. A publication must, in general, be committing a crime (for example, reporters burglarizing someone's office to obtain information about a news item); violating the law in publishing a particular article or issue (printing obscene material, copyright infringement, libel, breaking a non-disclosure agreement); directly threatening national security; or causing or potentially causing an imminent emergency (the "clear and present danger" standard) to be ordered stopped or otherwise suppressed, and then usually only the particular offending article or articles in question will be banned, while the newspaper itself is allowed to continue operating and can continue publishing other articles.

In the U.S. the term underground newspaper generally refers to an independent (and typically smaller) newspaper focusing on unpopular themes or counterculture issues. Typically, these tend to be politically to the left or far left.

The North American countercultural press of the 1960s drew inspiration from predecessors that had begun in the 1950s, such as the Village Voice and Paul Krassner's satirical paper The Realist. Arguably, the first underground newspaper of the 1960s was the Los Angeles Free Press, founded in 1964 and first published under that name in 1965. In mid-1966, the cooperative Underground Press Syndicate (UPS) was formed at the instigation of Walter Bowart, the publisher of another early paper, the East Village Other. The UPS allowed member papers to freely reprint content from any of the other member papers. One of the most notorious underground newspapers to join UPS and rallied activists, poets, and artists by giving them uncensored voice was the NOLA Express in New Orleans. Started by Robert Head and Darlene Fife as part of political protests and extending the "mimeo revolution" by protest and freedom-of-speech poets during the 1960s, NOLA Express was also a member of COSMEP (Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publishers. These two affiliations with organizations that were often at cross purposes made NOLA Express one of the most radical and controversial publications of the counterculture movement.[1] Part of the controversy about NOLA Express included graphic photographs and illustrations that many in today's society would be banned as pornographic.

Charles Bukowski's syndicated column, Notes of a Dirty Old Man, ran in NOLA Express, and Franciso McBride's illustration for the story "The Fuck Machine" was considered sexist, pornographic, and created an uproar. All of this controversy helped to increase the readership and bring attention to the political causes that editors Fife and Head supported.[2]

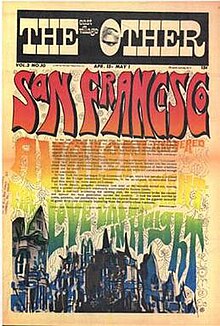

Other prominent underground papers included the San Francisco Oracle, the Berkeley Barb and Berkeley Tribe (Berkeley, California); Fifth Estate (Detroit), Other Scenes (dispatched from various locations around the world by John Wilcox); The Helix (Seattle); Avatar (Boston); The Chicago Seed; The Great Speckled Bird (Atlanta); The Rag (Austin, Texas); Space City News (later Space City!) (Houston); Rat Subterranean News (later "Women's LibeRATion") (New York City); The Spectator (Bloomington, Indiana); The Inquisition (Charlotte, North Carolina), and in Canada, The Georgia Straight (Vancouver, BC). By 1969, virtually every sizeable city or college town in North America boasted at least one underground newspaper.

The underground press phenomenon proved short-lived. By 1973, many underground papers had folded, at which point the Underground Press Syndicate acknowledged the passing of the undergrounds and renamed itself the Alternative Press Syndicate. That organization soon collapsed, to be supplanted by the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies.

During the 1960s and 1970s, there were also a number of left political periodicals with some of the same concerns of the underground press. Some of these periodicals joined the Underground Press Syndicate to gain services such as microfilming, advertising, and the free exchange of articles and newspapers. Examples include The Black Panther (the paper of the Black Panther Party, Oakland, California), and the Guardian, New York City; both of which had national distribution. The U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conducted surveillance and disruption activities on the underground press in the United States, including a campaign to destroy the alternative agency Liberation News Service. As part of its COINTELPRO designed to discredit and infiltrate radical New Left groups, the FBI also launched phony underground newspapers such as the Armageddon News at Indiana University Bloomington, The Longhorn Tale at the University of Texas at Austin, and the Rational Observer at American University in Washington, D.C. The FBI also ran the Pacific International News Service in San Francisco, the Chicago Midwest News, and the New York Press Service.

The Georgia Straight outlived the underground movement, evolving into an alternative weekly still published today; Fifth Estate survives as an anarchist magazine. Most others died with the era. Given the nature of alternative journalism as a subculture, some staff members from underground newspapers became staff on the newer alternative weeklies, even though there was seldom institutional continuity with management or ownership. An example is the transition in Denver from the underground Chinook, to Straight Creek Journal, to Westword [2], an alternative weekly still in publication. Some underground and alternative reporters, cartoonists, and artists moved on to work in corporate media or in academia.

Ray Mungo, in his classic account of the American underground press, Famous Long Ago, gave a cynical account of the origins of the typical underground newspaper: "Lots of radicals will give you a very precise line about why their little newspaper was started and what needs it fulfills and most of that stuff is bull. You see, the point is they've got nothing to do and the prospect of holding a straight job is so dreary that they join 'the movement' and start hitting up people for money to live, on the premise that they're involved in critical social change blah blah blah."

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives – Left History – Libraries & Archives – Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions