Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Tiananmen Square protests of 1989

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2010) |

| Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||

| Tank Man – This famous photo, taken on 5 June 1989 by photographer Jeff Widener, shows the PLA's advancing tanks halting for an unknown man near Tiananmen Square. | |||||||

| Chinese | ÅÅää» | ||||||

| Literal meaning | June Fourth Incident | ||||||

|

|||||||

| alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | Å«äÆÉ | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | Å«äÆÈ¿ | ||||||

| Literal meaning | '89 people's movement | ||||||

|

|||||||

The Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, referred to in much of the world as the Tiananmen Square massacre and in the People's Republic of China (PRC) as the June Fourth Incident (officially to avoid confusion with two prior Tiananmen Square protests), were a series of demonstrations in and near Tiananmen Square in Beijing in the PRC beginning on 14 April 1989. Led mainly by students and intellectuals, the protests occurred in a year that saw the collapse of a number of communist governments around the world. An intelligence report received by the Soviet politburo estimated that 3,000 protesters were killed, according to a document found in the Soviet archive.[1]

The protests were sparked by the death of Hu Yaobang, an official known for tolerating dissent, whom protesters wanted to mourn.[2] By the eve of Hu's funeral, 100,000 people had gathered at Tiananmen Square.[3] The protests lacked a unified cause or leadership; participants included Communist Party of China members and Trotskyists as well as liberal reformers, who were generally against the government's authoritarianism and voiced calls for economic change[4] and democratic reform[4] within the structure of the government. The demonstrations centered in Tiananmen Square to begin with but then later in the streets around the square, in Beijing, but large-scale protests also occurred in cities throughout China, including Shanghai, which remained peaceful throughout the protests.

The movement lasted seven weeks after Hu's death on 15 April. The number of deaths is not known. There is no video footage or evidence of any kind showing violence in the square itself.[citation needed]

Following the conflict, the government conducted widespread arrests of protesters and their supporters, cracked down on other protests around China, banned the foreign press from the country and strictly controlled coverage of the events in the PRC press. Members of the Party who had publicly sympathized with the protesters were purged, with several high-ranking members placed under house arrest, such as General Secretary Zhao Ziyang. There was widespread international condemnation of the PRC government's use of force against the protesters.[4]

Contents |

In the Chinese language, the incident is most commonly known as the June Fourth Movement, the June Fourth Incident or colloquially, simply Six-four (Chinese: ÅÅ; pinyin: Li-S; June 4). The nomenclature of the former is consistent with the customary names of the other two great protest actions that occurred in Tiananmen Square: the May Fourth Movement of 1919, and the April Fifth Movement of 1976.

'4 June' refers to the day on which the People's Liberation Army cleared Tiananmen Square of protesters, although the order to proceed into Tiananmen as well as its actual operation began on the evening of 3 June. Other names which have been used in the Chinese language include June Fourth Massacre or Chinese: ÅÅÅÆ; pinyin: Li-S Tshä and June Fourth Crackdown. The government of the People's Republic of China has referred to the event as the Political Turmoil between Spring and Summer of 1989.[5]

Other names, such as the 89 Pro-democracy Movement (simplified Chinese: Å«äÆÈ¿; traditional Chinese: Å«äÆÉ) are also used to describe the event broadly in its entirety. The date May 35th is sometimes substituted for 4 June to avoid restrictions that the government of China places on the Internet.[6] In English, the more descriptive terms Tiananmen Square Massacre or Tiananmen Square Crackdown are often used to describe the 4 June events on most media sources.

In East Germany the events in Beijing were euphamistically known as the "Chinese Solution" (Chinesische Lsung).[7]

Since 1978, Deng Xiaoping had led a series of economic and political reforms which had led to the gradual implementation of a market economy and some political liberalization that relaxed the system set up by Mao Zedong.

Some students and intellectuals believed that the reforms had not gone far enough and that China needed to reform its political system.[citation needed] They were also concerned about the social controls that the Communist Party of China still had.[citation needed] This group had also seen the political liberalization that had been undertaken in the name of glasnost by Mikhail Gorbachev, so they had been hoping for comparable reform. Many workers who took part in the protests also wanted democratic reform, but opposed the new economic policies. That is, there were both protesters supporting and against economic liberalisation; however, almost all protesters supported political liberalization, to varying degrees.[citation needed]

The Tiananmen Square protests were in large measure sparked by the death of former Secretary General Hu Yaobang,[2] whose resignation from the position of Secretary General of the CPC was announced on 16 January 1987.[citation needed] His forthright calls for "rapid reform" and his almost open contempt of "Maoist excesses" had made him a suitable scapegoat in the eyes of Deng and others, after the pro-democracy student protests of 1986–1987.[8]

Included in his resignation was also a "humiliating self-criticism", which he was forced by the Central Committee of the Communist Party to issue. Hu's sudden death, due to heart attack, on 15 April 1989 provided a perfect opportunity for the students to gather once again, not only to mourn the deceased Secretary General, but also to have their voices heard in "demanding a reversal of the verdict against him" and bringing renewed attention to the important issues of the 1986–1987 pro-democracy protests and possibly also to those of the Democracy Wall protests in 1978–1979.[9]

Small voluntary civilian gatherings started on 15 April around Monument to the People's Heroes in the middle of the Tiananmen Square in the form of mourning for Hu Yaobang.

On the same date of 15 April, many students at Peking University and Tsinghua University expressed their sorrow and mourning for Hu Yaobang by posting eulogies inside the campus and erecting shrines, and joined the civilian mourning in Tiananmen Square in a piecemeal fashion. Organized student gatherings started outside of Beijing on a small scale in Xi'an and Shanghai on 16 April.

On the afternoon of 17 April in Beijing, 500 students from China University of Political Science and Law marched to the eastern gate of the Great Hall of the People, part of Tiananmen Square, and commenced mourning activities for Hu Yaobang. The gathering in front of the Great Hall of the People was soon deemed obstructive to the normal operation of the building, so police intervened and attempted to disperse the students by persuasion. The gathering featured speakers from various backgrounds giving public speeches (mostly anonymous) commemorating Hu Yaobang, expressing their concerns of social problems.

Starting at midnight on the night of 17 April, three thousand students from Peking University marched from the campus towards Tiananmen Square, and soon nearly a thousand students from Tsinghua University joined the ranks. Upon arrival, they soon joined forces with students and civilians who were in the Square earlier. As its size grew, the gathering gradually evolved into a protest, as students began to draft a list of pleas and suggestions (List of Seven Demands) that they wanted the government to listen to and carry through: (1) affirm as correct Hu Yaobang's views on democracy and freedom; (2) admit that the campaigns against spiritual pollution and bourgeois liberalization had been wrong; (3) publish information on the income of state leaders and their family members; (4) end the ban on privately run newspapers and permit freedom of speech; (5) increase funding for education and raise intellectuals' pay; (6) end restrictions on demonstrations in Beijing; and (7) hold democratic elections to replace government officials who made bad policy decisions. In addition, they demanded that the government-controlled media print and broadcast their demands and that the government respond to them publicly.[10]

On the morning of 18 April, the students remained in the square. Some gathered around the Monument to the People's Heroes singing patriotic songs and listening to impromptu speeches by student organizers. Another group of students sat in front of the Great Hall of the People, the office of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress; they demanded to see members of the Standing Committee and show them the List of Seven Demands. Meanwhile, a few thousand students gathered in front of the Zhongnanhai building complex, the residence of the government, demanding to see government leaders and get answers to their earlier demands. Students tried to muscle their way through the gate by pushing, but security and police, locking arms, formed a cordon that eventually deterred students' attempts to enter through the gate. Students then staged a sit-in. Some government officials did unofficially meet with student representatives, but without an official response, frustrations continued to mount.

On 20 April, police finally dispersed the students in front of the Zhongnanhai by force, employing batons, and minor clashes were reported. The protests in Tiananmen Square gained momentum after news of the confrontation between students and police spread; the belief by students that the Chinese media was distorting the nature of their activities also led to increased support.[citation needed]

On the night of 21 April, the day before Hu's funeral, some 100,000 students marched on Tiananmen Square, gathering there before the square could be closed off for the funeral.

From 21 April to 23 April, students from Beijing called for a strike at universities, which included teachers and students boycotting classes. The government, which was well aware of the political storm caused by the now-legitimized 1976 Tiananmen Incident, was alarmed. On 26 April, following an internal speech made by Deng Xiaoping, the CPC's official newspaper People's Daily issued a front-page editorial titled Uphold the flag to clearly oppose any turmoil, attempting to rally the public behind the government, and accused "extremely small segments of opportunists" of plotting civil unrest.[11] The statement enraged the students, and on 27 April about 50,000 students assembled on the streets of Beijing, disregarding the warning of military action made by authorities, and demanded that the government retract the statement.

In Beijing, a majority of students from the city's numerous colleges and universities participated with support of their instructors and other intellectuals. The students rejected official Communist Party-controlled student associations and set up their own autonomous associations. The students viewed themselves as Chinese patriots, as the heirs of the May Fourth Movement for "science and democracy" of 1919. The protests also evoked memories of the Tiananmen Square protests of 1976 which had eventually led to the ousting of the Gang of Four. From their origins as a memorial to Hu Yaobang, who was seen by the students as an advocate of democracy, the students' activities gradually developed over the course of their demonstration from protests against corruption into demands for freedom of the press and an end to, or the reform of, the rule of the PRC by the Communist Party of China and Deng Xiaoping, the de facto paramount Chinese leader. Partially successful attempts were made to reach out and network with students in other cities and with workers.[citation needed]

While the protests lacked a unified cause or leadership, participants were generally against authoritarianism and voiced calls for democratic reform[4] within the structure of the government. Unlike the Tiananmen protests of 1987, which consisted mainly of students and intellectuals, the protests in 1989 commanded widespread support from the urban workers who were alarmed by the new economic reforms, growing inflation, and corruption. In Beijing, they were supported by a large number of people. Similar numbers were found in major cities throughout China such as Urumqi, Shanghai, and Chongqing; and later in Hong Kong, Taiwan and Chinese communities in North America and Europe.

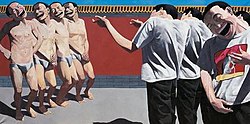

"The Goddess of Democracy" carved by students from the Central Academy of Fine Arts and erected in the Square during the protest.

|

Zhao Ziyang speaks on 19 May 1989. Wen Jiabao, then Director of the Central Party Office, was also present (2nd from right in black). This was Zhao's last public appearance before he was placed under house arrest, where he remained until his death

|

On 4 May, approximately 100,000 students and workers marched in Beijing making demands for free media and a formal dialogue between the authorities and student-elected representatives. A declaration demanded the government to accelerate political reform.[4]

The government rejected the proposed dialogue, only agreeing to talk to members of appointed student organizations. On 13 May, two days prior to the highly-publicized state visit by the reform-minded Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, huge groups of students occupied Tiananmen Square and started a hunger strike, insisting the government withdraw the accusation made in the People's Daily editorial and begin talks with the designated student representatives. Hundreds of students went on hunger strikes and were supported by hundreds of thousands of protesting students and part of the population of Beijing, for one week.

Protests and strikes began at colleges in other cities, with many students traveling to Beijing to join the demonstration. Generally, the demonstration at Tiananmen Square was well-ordered, with daily marches of students from various Beijing area colleges displaying their solidarity with the boycott of college classes and with the developing demands of the protest. The students sang The Internationale, the world socialist anthem, on their way to and within the square.[12] The students even showed a surprising gesture of respect to the government by helping police arrest three men from Hunan Province, including Yu Zhijian, Yu Dongyue, and Lu Decheng who had thrown ink on the large portrait of Mao that hangs from Tiananmen, just north of the square.[13][14] The three young men were later sentenced to prison for, respectively, life, 20 years, and 16 years.[15] However, two were freed after 10 years and Yu Dongyue after nearly 17 years.

The students ultimately decided that in order to sustain their movement and impede any loss of momentum, a hunger strike would need to be enacted. The students' decision to undertake the hunger strike was a defining moment in their movement. The hunger strike began in May 1989 and grew to include "more than one thousand persons".[16] The hunger strike brought widespread support for the students and "the ordinary people of Beijing rallied to protect the hunger strikers...because the act of refusing sustenance and courting government reprisals convinced onlookers that the students were not just seeking personal gains but (were) sacrificing themselves for the Chinese people as a whole".[17]

The hunger strike not only gained significant support nationally for the students, but also rang further alarms in China's top leadership. The national press, then still relatively free to cover ongoing events without propagating the party line, aired the talks between Premier Li Peng and student leaders on the evening of 18 May. During the talks Wu'er Kaixi, Wang Dan, and others openly accused the government for being too slow to react and rebuked Li Peng personally for lacking the "sincerity to conduct real discussions". The discussion did not yield much results, but gained student leaders prominent airtime on China's national television.[18] Li Peng and other leaders, however, maintained the government was only trying to "maintain order", but alluded to the students actions as "patriotic".

As the hunger strike escalated, numerous political and civil organizations around the country voiced their concern for the students, many empathizing with their positions. The Chinese Red Cross issued a special notice and sent in a large number of personnel to provide medical services to the hunger strikers on the Square. For the first time, on 19 May, two of the highest ranked members of China's central leadership, Premier Li Peng and General Secretary Zhao Ziyang went to Tiananmen personally in an attempt to neutralize the situation. At 4:50 am, Zhao Ziyang went to the Square and made a speech urging the students to end the hunger strike. Part of his speech was to become a famous quote, when he said, referring to the older generation of people in China, "We are already old, it doesn't matter to us any more." In contrast, the students were young and he urged them to stay healthy and not to sacrifice themselves so easily. Zhao's emotional speech was applauded by some students on the Square; it would be his last public appearance.

Partially successful attempts were made to negotiate with the PRC government, who were located nearby in Zhongnanhai, the Communist Party headquarters and leadership compound. Because of the visit of Mikhail Gorbachev, foreign media were present in China in large numbers. Their coverage of the protests was extensive and generally favorable towards the protesters, but pessimistic that they would attain their goals. Toward the end of the demonstration, on 30 May, a Goddess of Democracy statue was erected in the Square and came to symbolize the protest to television viewers worldwide.

The Standing Committee of the Politburo, along with the party elders (retired but still-influential former officials of the government and Party), were at first hopeful that the demonstrations would be short-lived or that cosmetic reforms and investigations would satisfy the protesters. They wished to avoid violence if possible, and relied at first on their far-reaching Party apparatus in attempts to persuade the students to abandon the protest and return to their studies. One barrier to effective action was that the leadership itself supported many of the demands of the students, especially the concern with corruption. However, one large problem was that the protests contained many people with varying agendas, and hence it was unclear with whom the government could negotiate, and what the exact demands of the protesters were. The confusion and indecision among the protesters was also mirrored by confusion and indecision within the government. The official media mirrored this indecision as headlines in the People's Daily alternated between sympathy with the demonstrators and denouncing them.

Among the top leadership, General Secretary Zhao Ziyang was strongly in favour of a soft approach to the demonstrations, while Li Peng was seen to argue in favour of military action. Ultimately the decision to forcefully intervene on the demonstrations was made by a group of Party elders, who saw abandonment of single-party rule as a return of the chaos of the Cultural Revolution.[19] Although most of these people had no official position, they were able to control the military. Deng Xiaoping was chairman of the Central Military Commission and was able to declare martial law; Yang Shangkun was President of the People's Republic of China, which, although a symbolic position under the 1982 Constitution, was legally the Commander-in-Chief of the Chinese armed forces. The Party elders believed that lengthy demonstrations were a threat to the stability of the country. The demonstrators were seen as tools of advocates of "bourgeois liberalism" who were pulling the strings behind the scenes, as well as tools of elements within the party who wished to further their personal ambitions.[20]

At the beginning of the movement, the Chinese news media had a rare opportunity to broadcast the news without heavy government censorship. Most of the news media were free to write and report however they wanted, due to lack of control from the central and local governments. The news was spread quickly across the land. According to Chinese news media's report, students and workers in over 400 cities, including cities in Inner Mongolia, also organized and started to protest.[21] People also traveled to the capital to join the protest in the Square.

University students in Shanghai also took to the streets to commemorate the death of Hu Yaobang and protest against certain policies of the government. In many cases, these were supported by the universities' Party committees. Jiang Zemin, then-Municipal Party Secretary, addressed the student protesters in a bandage and 'expressed his understanding', as he was a former student agitator before 1949. But at the same time, he moved swiftly to send in police forces to control the streets and to purge Communist Party leaders who had supported the students.

On 19 April, the editors of the World Economic Herald, a magazine close to reformists, decided to publish, in their 24 April #439 issue, a commemorative section on Hu. Inside was an article by Yan Jiaqi, which commented favourably on the Beijing student protests on 18 April and called for a reassessment of Hu's purge in 1987. On 21 April, a party official of Shanghai asked the editor in chief, Qin Benli, to change some passages. Qin Benli refused, so the official turned to Jiang Zemin, who demanded that the article be censored. By that time, a first batch of copies of the paper had already been delivered. The remaining copies were published with a blank page.[22] On 26 April, the "People's Daily" published its editorial condemning the student protest. Jiang followed this cue and suspended Qin Benli.

In Hong Kong, on 27 May 1989, over 300,000 people gathered at Happy Valley Racecourse for a gathering called "Democratic songs dedicated for China." Many Hong Kong celebrities sang songs and expressed their support for the students in Beijing. The following day, a procession of 1.5 million people, one fourth of Hong Kong's population, led by Martin Lee, Szeto Wah and other organization leaders, paraded through Hong Kong Island. Across the world, especially where Chinese lived, people gathered and protested. Many governments, such as those of the USA, Japan, etc., also issued warnings advising their own citizens not to go to the PRC.

Although the government declared martial law on 20 May, the military's entry into Beijing was blocked by throngs of protesters, and the army was eventually ordered to withdraw, which it did on 24 May.[23]

Meanwhile, the demonstrations continued. The hunger strike was approaching the end of the third week, and the government resolved to end the matter before deaths occurred. After deliberation among Communist party leaders, the use of the military to resolve the crisis was ordered, and a deep divide in the politburo resulted. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang was ousted from political leadership as a result of his support for the demonstrators. The military also lacked unity on the issue, and purportedly did not indicate immediate support for military action, leaving the central leadership scrambling to search for individual divisions willing to comply with their orders.[citation needed]

|

|

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page.

|

Soldiers and tanks from the 27th and 38th Armies of the People's Liberation Army were sent to take control of the city. The 27th Army was led by a commander related to Yang Shangkun. In a press conference, US President George H. W. Bush announced sanctions on the People's Republic of China, following calls to action from members of Congress such as US Senator Jesse Helms. The President suggested[vague] intelligence he had received indicated some disunity in China's military ranks, and even the possibility of clashes within the military during those days.[citation needed]

Intelligence reports also indicated that 27th and 28th units were brought in from outside provinces because the local PLA were considered to be sympathetic to the protest and to the people of the city.[citation needed] Reporters described elements of the 27th as having been most responsible for civilian deaths. After their attack on the square, the 27th reportedly established defensive positions in Beijing – not of the sort designed to counter a civilian uprising, but as if to defend against attacks by other military units.

As word spread that hundreds of thousands of troops were approaching from all four corners of the city, Beijingers flooded the streets to block them, as they had done two weeks earlier. People set up barricades at every major intersection. Protesters threw Molotov cocktails and burned vehicles. At about 10:30 pm, near the Muxidi apartment buildings (home to high-level Party officials and their families), protesters threw rocks and Molotov cocktails at police and army vehicles. As can be seen in numerous photographs many vehicles were set on fire in the streets all around Tiananmen some with their occupants still inside them. There were reports of soldiers being burned alive in their armoured personnel carriers while others were beaten to death. Then the soldiers started firing live ammunition at some of the protesters. Some people in nearby apartment blocks were hit.[24]

The battle raged in the streets surrounding the Square, with protesters repeatedly advancing toward the PLA and constructing barricades with vehicles, while the PLA attempted to clear the streets using tear gas, rifles, and tanks. Many injured citizens were saved by rickshaw drivers who ventured into the no-man's-land between the soldiers and crowds and carried the wounded off to hospitals. After the attack on the square, live television coverage showed many people wearing black armbands in protest against the government, crowding various boulevards or congregating by burnt out and smoking barricades. In a couple of cases, soldiers were pulled from tanks, beaten and killed by protesters.[25]

Meanwhile, the PLA systematically established checkpoints around the city, chasing after protesters and blocking off the university district.

Earlier, within the Square itself, there had been a debate between those who wished to withdraw peacefully, including Han Dongfang, and those who wished to stand within the square, such as Chai Ling.[citation needed]

At about 1:00 am, the army finally reached Tiananmen Square and waited for orders from the government. The soldiers had been told not to open fire, but they had also been told that they must clear the square by 6:00 am – with no exceptions or delays. They made a final offer of amnesty if the few thousand remaining students would leave. About 4:00 am, student leaders put the matter to a vote: Leave the square, or stay and face the consequences.[25]

APCs (Armoured Personnel Carriers) rolled on up the roads, firing ahead and off to the sides, perhaps killing or wounding their own soldiers in the process. BBC reporter Kate Adie spoke of "indiscriminate fire" within the square. Eyewitness reporter Charlie Cole also saw Chinese soldiers firing Type 56 assault rifles into the crowd near an APC which had just been torched and its crew killed; many were killed and wounded that night.[26]

Students who sought refuge in buses were pulled out by groups of soldiers and beaten with heavy sticks. Even students attempting to leave the square were beset by soldiers and beaten. Leaders of the protest inside the square, where some had attempted to erect flimsy barricades ahead of the APCs, were said to have "implored" the students not to use weapons (such as Molotov cocktails) against the oncoming soldiers. Meanwhile, many students apparently were shouting, "Why are you killing us?" Around 4 or 5 am the following morning, 4 June, Cole reports to have seen tanks smashing into the square, crushing vehicles and people with their treads.[26] By 5:40 am 4 June, the Square had been cleared.

BBC 2 June 2009[27] James Miles, who was the BBC's Beijing correspondent at the time, stated:

I and others conveyed the wrong impression. There was no massacre on Tiananmen Square... Protesters who were still in the square when the army reached it were allowed to leave after negotiations with martial law troops (Only a handful of journalists were on hand to witness this moment [...]). [...] There was no Tiananmen Square massacre, but there was a Beijing massacre.

Sinomania[unreliable source?] maintain that there was a Spanish film crew in the square which filmed the last 5000 students leaving the square just before dawn on 4 June after negotiating safe passage with the military.[28] Richard Roth of CBS reported that he and a colleague were on the south portico of the Great Hall of the People (which forms one of the borders of the Square) led by Richard Roth. In the words of eyewitness CBS news correspondent Richard Roth:[29]

Derek Williams and I were driven in a pair of army jeeps right through the square, almost along its full length, and into the Forbidden City. Dawn was just breaking. There were hundreds of troops in the square ... But we saw no bodies, injured people, ambulances or medical personnel–in short, nothing to even suggest, let alone prove, that a "massacre" had recently occurred in that place... some have found it uncomfortable that all this conforms with what the Chinese government has always claimed, perhaps with a bit of sophistry: that there was no "massacre in Tiananmen Square." But there's no question many people were killed by the army that night around Tiananmen Square, and on the way to it – mostly in the western part of Beijing. Maybe, for some, comfort can be taken in the fact that the government denies that, too.

PBS reported that, on the morning of 5 June, protesters tried to enter the blockaded square but were shot at by the soldiers. The soldiers shot them in the back when they were running away. These actions were repeated several times.[30]

The suppression of the protest was immortalized in Western media by the famous video footage and photographs of a lone man in a white shirt standing in front of a column of tanks which were attempting to drive out of Tiananmen Square. Taken on 5 June as the column approached an intersection on the Chang'an Avenue, the footage depicted the unarmed man standing in the center of the street, halting the tanks' progress. As the tank driver attempted to go around him, the "Tank Man" moved into the tank's path. He continued to stand defiantly in front of the tanks for some time, then climbed up onto the turret of the lead tank to speak to the soldiers inside. After returning to his position blocking the tanks, the man was pulled aside by a group of people, on which the identity of whom eyewitnesses are divided.[31]

Eyewitness Jan Wong is convinced the group were concerned citizens helping him away, while Charlie Cole believes that "Tank Man" was probably executed after being taken from the tank by secret police, since the Chinese government could never produce him to hush the outcry from many countries.[26] Time Magazine dubbed him The Unknown Rebel and later named him one of the 100 most influential people of the 20th century. British tabloid the Sunday Express reported that the man was 19-year-old student Wang Weilin; however, the veracity of this claim is dubious.

What happened to the 'Tank Man' following the demonstration is not known. In a speech to the President's Club in 1999, Bruce Herschensohn–former deputy special assistant to President Richard Nixon–reported that he was executed 14 days later. In Red China Blues: My Long March from Mao to Now, Jan Wong writes that the man is still alive and hiding in mainland China. In Forbidden City, Canadian children's author William Bell, claims the man was named Wang Ai-min and was killed on 9 June after being taken into custody. The last official statement from the PRC government about the "Tank Man" came from Premier Jiang Zemin in a 1990 interview; when asked about the whereabouts of the "Tank Man", Jiang responded: "I think never killed."[32]

After order was restored in Beijing on 4 June, protests continued in much of mainland China for several days. There were large protests in Hong Kong, where people again wore black in protest. There were protests in Guangzhou, and large-scale protests in Shanghai with a general strike. There were also protests in other countries, many adopting the use of black armbands as well. However, the government soon regained control. A political purge followed in which officials responsible for organizing or condoning the protests were removed, and protest leaders jailed. According to Amnesty International at least 300 people were killed in Chengdu on 5 June. Troops in Chengdu used concussion grenades, truncheons, knives and electric cattle prods against civilians. Hospitals were ordered to not accept students and on the second night the ambulance service was stopped by police.[33]

The number of dead and wounded remains unclear because of the large discrepancies between the different estimates. Some Beijinger and journalists reported that troops burned the bodies of many citizens to destroy the evidence of the killings.[34]

Some of the early estimates were based on reports of a figure of 2,600 from the Chinese Red Cross. The Chinese Red Cross has denied ever providing such a figure.[34] According to a PBS Frontline report, this figure was quickly retracted under intense pressure from the government.[35] The official Chinese government figure is 241 dead, including soldiers, and 7,000 wounded.[35]

According to an analysis by Nicholas D. Kristof of The New York Times, "The true number of deaths will probably never be known, and it is possible that thousands of people were killed without leaving evidence behind. But based on the evidence that is now available, it seems plausible that about fifty soldiers and policemen were killed, along with 400 to 800 civilians."[34] An intelligence report received by the Soviet politburo estimated that 3,000 protesters were killed, according to a document found in the Soviet archive.[1]

The Chinese government has maintained that there were no deaths within the square itself, although videos taken there at the time recorded the sound of gunshots. State Council claimed that the basic statistics were: "Five thousand PLA soldiers and officers wounded, and more than two thousand local people (counting students, city people, and protesters together) also wounded." Chinese commentators have pointed out that this obvious imbalance in casualties questions the military competence of the PLA. They also said no one died on Tiananmen Square itself.[36] Yuan Mu, the spokesman of the State Council, said that a total of 23 people died, most of them students, along with a number of people he described as "ruffians".[37] According to Chen Xitong, Beijing mayor, 200 civilians and several dozen soldiers died.[38] Other sources stated that 3,000 civilians and 6,000 soldiers were injured.[39] In May 2007, CPPCC member from Hong Kong, Chang Ka-mun said 300 to 600 people were killed in Tiananmen Square. He echoed that "there were armed thugs who weren't students."[40]

According to The Washington Post first Beijing bureau chief, Jay Mathews: "A few people may have been killed by random shooting on streets near the square, but all verified eyewitness accounts say that the students who remained in the square when troops arrived were allowed to leave peacefully. Hundreds of people, most of them workers and passersby, did die that night, but in a different place and under different circumstances."[41] US ambassador James Lilley's account of the massacre notes that US State Department diplomats witnessed Chinese troops opening fire on unarmed people and based on visits to hospitals around Beijing a minimum of hundreds had been killed.[42]

A strict focus on the number of deaths within Tiananmen Square itself does not give an accurate picture of the carnage and overall death count, since Chinese civilians were fired on in the streets surrounding Tiananmen Square. In addition, students are reported to have been fired on after they left the Square, especially in the area near the Beijing concert hall.[34]

Estimates of deaths from different sources, in descending order:

The events at Tiananmen were the first of their type shown in detail on Western television.[49] The Chinese government's response was denounced, particularly by Western governments and media.[50] Criticism came from both Western and Eastern Europe, North America, Australia and some east Asian and Latin American countries. Notably, many Asian countries remained silent throughout the protests; the government of India responded to the massacre by ordering the state television to pare down the coverage to the barest minimum, so as not to jeopardize a thawing in relations with China, and to offer political empathy for the events.[51] North Korea, Cuba, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany, among others, supported the Chinese government and denounced the protests.[50] Overseas Chinese students demonstrated in many cities in Europe, America, the Middle East and Asia.[52]

![]() UN: Secretary-General Javier Perez de Cuellar was concerned at the incident, adding that the government should uphold the utmost restraint, but also noted that the UN Charter prohibits interference in member states' internal affairs (especially member states with a Security Council veto).[53]

UN: Secretary-General Javier Perez de Cuellar was concerned at the incident, adding that the government should uphold the utmost restraint, but also noted that the UN Charter prohibits interference in member states' internal affairs (especially member states with a Security Council veto).[53]

![]() The European Economic Community condemned the government response and cancelled all high level contacts and loans. They planned a resolution at the UNHCR criticising China's human rights record.[54][55] The EU maintains an arms embargo against China to this day.

The European Economic Community condemned the government response and cancelled all high level contacts and loans. They planned a resolution at the UNHCR criticising China's human rights record.[54][55] The EU maintains an arms embargo against China to this day.

![]() Australia: The Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, wept at a memorial service in the Great Hall in Parliament. The Australian government granted Chinese students a four year amnesty to stay in Australia.[49]

Australia: The Prime Minister, Bob Hawke, wept at a memorial service in the Great Hall in Parliament. The Australian government granted Chinese students a four year amnesty to stay in Australia.[49]

![]() Burma: The government supported the actions of the Chinese government, while opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi condemned them, saying: "We deplore it. It happened in Burma and we wanted the world to stand by Burma, so we stand by the Chinese students."[56]

Burma: The government supported the actions of the Chinese government, while opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi condemned them, saying: "We deplore it. It happened in Burma and we wanted the world to stand by Burma, so we stand by the Chinese students."[56]

![]() Canada: The External Affairs Minister Joe Clark described the incident as "inexcusable" and issued a statement: "We can only express horror and outrage at the senseless violence and tragic loss of life resulting from the indiscriminate and brutal use of force against students and civilians of Peking."[57]

Canada: The External Affairs Minister Joe Clark described the incident as "inexcusable" and issued a statement: "We can only express horror and outrage at the senseless violence and tragic loss of life resulting from the indiscriminate and brutal use of force against students and civilians of Peking."[57]

![]() Czechoslovakia: The government of Czechoslovakia supported the Chinese governments response, expressing the idea that China would overcome its problems and further develop socialism. In response, the Chinese side "highly valued the understanding shown by the Czechoslovak Communist Party and people" for suppressing the "anti-socialist" riots in Beijing.[58]

Czechoslovakia: The government of Czechoslovakia supported the Chinese governments response, expressing the idea that China would overcome its problems and further develop socialism. In response, the Chinese side "highly valued the understanding shown by the Czechoslovak Communist Party and people" for suppressing the "anti-socialist" riots in Beijing.[58]

![]() France: The French Foreign Minister, Roland Dumas, said he was "dismayed by the bloody repression" of "an unarmed crowd of demonstrators."[59]

France: The French Foreign Minister, Roland Dumas, said he was "dismayed by the bloody repression" of "an unarmed crowd of demonstrators."[59]

![]() East Germany: The government of the German Democratic Republic approved of the military action. On 8 June the Volkskammer unanimously passed a resolution in support of the Chinese government's use of force. High-ranking politicians from the ruling SED party, including Hans Modrow, Gnter Schabowski and Egon Krenz, were in China shortly afterward on a goodwill visit. In contrast, members of the general population, including ordinary SED party members, participated in protests against the actions of the Chinese government.[60]

East Germany: The government of the German Democratic Republic approved of the military action. On 8 June the Volkskammer unanimously passed a resolution in support of the Chinese government's use of force. High-ranking politicians from the ruling SED party, including Hans Modrow, Gnter Schabowski and Egon Krenz, were in China shortly afterward on a goodwill visit. In contrast, members of the general population, including ordinary SED party members, participated in protests against the actions of the Chinese government.[60]

![]() West Germany: The West German Foreign Ministry urged China "to return to its universally welcomed policies of reform and openness."[59]

West Germany: The West German Foreign Ministry urged China "to return to its universally welcomed policies of reform and openness."[59]

![]() Holy See: The Holy See of Vatican City has no official diplomatic relations with China, but Pope John Paul II expressed hope that the events in China would bring change.[59]

Holy See: The Holy See of Vatican City has no official diplomatic relations with China, but Pope John Paul II expressed hope that the events in China would bring change.[59]

![]() Hong Kong: The military action severely affected perceptions of the mainland. 200,000 people protested against the Chinese government's response, with the latter considering the protests as "subversive". The people of Hong Kong hoped that the chaos on the mainland would destabilize the Beijing Government and thus avert its reunification with the rest of mainland China. The Sino-British Joint Declaration was also called into question.[61][62] Demonstrations continued for several days, and wreaths were placed outside the Xinhua News Agency office in the city.[52] This further fuels the mass migration wave of Hong Kong people out of Hong Kong.

Hong Kong: The military action severely affected perceptions of the mainland. 200,000 people protested against the Chinese government's response, with the latter considering the protests as "subversive". The people of Hong Kong hoped that the chaos on the mainland would destabilize the Beijing Government and thus avert its reunification with the rest of mainland China. The Sino-British Joint Declaration was also called into question.[61][62] Demonstrations continued for several days, and wreaths were placed outside the Xinhua News Agency office in the city.[52] This further fuels the mass migration wave of Hong Kong people out of Hong Kong.

![]() Hungary: The Hungarian government, which was undergoing political reform, reacted strongly to the incident. The Foreign Minister described the events as a "horrible tragedy", and the government expressed "shock", adding that "fundamental human rights could not be exclusively confined to the internal affairs of any country." Demonstrations were held outside the Chinese embassy. Hungary was the only country in Europe to have substantially reduced relations with China in the aftermath of the events.[63]

Hungary: The Hungarian government, which was undergoing political reform, reacted strongly to the incident. The Foreign Minister described the events as a "horrible tragedy", and the government expressed "shock", adding that "fundamental human rights could not be exclusively confined to the internal affairs of any country." Demonstrations were held outside the Chinese embassy. Hungary was the only country in Europe to have substantially reduced relations with China in the aftermath of the events.[63]

![]() India: The government of India responded by ordering the state television to pare down the coverage to the barest minimum. The government–s monopoly over television two decades ago helped Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi signal to Beijing that India would not revel in China–s domestic troubles and offer some political empathy instead.[64]

India: The government of India responded by ordering the state television to pare down the coverage to the barest minimum. The government–s monopoly over television two decades ago helped Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi signal to Beijing that India would not revel in China–s domestic troubles and offer some political empathy instead.[64]

![]() Italy: The Italian Communist Party leader Achille Occhetto condemned the "unspeakable slaughter in progress in China".[65]

Italy: The Italian Communist Party leader Achille Occhetto condemned the "unspeakable slaughter in progress in China".[65]

![]() Japan: The Japanese government called the response "intolerable" and froze loans to China. Japan was also the first member of the G7 to restore high level relations with China in the following months.[66][67]

Japan: The Japanese government called the response "intolerable" and froze loans to China. Japan was also the first member of the G7 to restore high level relations with China in the following months.[66][67]

![]() Kuwait: Kuwait voiced understanding of the measures taken by the Chinese authorities to protect social stability.[68]

Kuwait: Kuwait voiced understanding of the measures taken by the Chinese authorities to protect social stability.[68]

![]() Macau: 150,000 protested in Macau.[69][70]

Macau: 150,000 protested in Macau.[69][70]

![]() Mongolia: Many reformists had been aware of the international reaction to the military action, and chose to follow the democratic changes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.[71][72]

Mongolia: Many reformists had been aware of the international reaction to the military action, and chose to follow the democratic changes in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.[71][72]

![]() Netherlands: The Dutch government froze diplomatic relations with China, and summoned the Chinese Charg d'Affaires Li Qin Ping expressing shock at the "violent and brutal actions of the People's Liberation Army."[52]

Netherlands: The Dutch government froze diplomatic relations with China, and summoned the Chinese Charg d'Affaires Li Qin Ping expressing shock at the "violent and brutal actions of the People's Liberation Army."[52]

![]() Philippines: President Corazon Aquino expressed sadness at the incident, urging the Chinese government to "urgently and immediately take steps to stop the aggressive and senseless killing by its armed forces".[57] Socialist labor organization KMU at first initially supported the action taken by Chinese authorities, though later issued a "rectified position" which blamed "insufficient information and improper decision making process".[73]

Philippines: President Corazon Aquino expressed sadness at the incident, urging the Chinese government to "urgently and immediately take steps to stop the aggressive and senseless killing by its armed forces".[57] Socialist labor organization KMU at first initially supported the action taken by Chinese authorities, though later issued a "rectified position" which blamed "insufficient information and improper decision making process".[73]

![]() Poland: The Polish government criticised the response of the Chinese government but not the government itself. A government spokesman called the incident "tragic", with "sincere sympathy for the families of those killed and injured." Daily protests and hunger strikes took place outside the Chinese embassy in Warsaw. The government also expressed hope that it did not affect Sino-Polish relations.[63]

Poland: The Polish government criticised the response of the Chinese government but not the government itself. A government spokesman called the incident "tragic", with "sincere sympathy for the families of those killed and injured." Daily protests and hunger strikes took place outside the Chinese embassy in Warsaw. The government also expressed hope that it did not affect Sino-Polish relations.[63]

After Solidarity assumed the political leadership of Poland, the new government issued new stamps to commemorate the student protests in Tiananmen Square in China in the Spring of 1989.[74]

![]() Romania: Nicolae CeauÅescu praised the military action, and in a reciprocal move, China sent Qiao Shi to the Romanian Communist Party Congress in August 1989, at which CeauÅescu was re-elected.[75] CeauÅescu would later be overthrown and executed by the people of his country in December of that same year.

Romania: Nicolae CeauÅescu praised the military action, and in a reciprocal move, China sent Qiao Shi to the Romanian Communist Party Congress in August 1989, at which CeauÅescu was re-elected.[75] CeauÅescu would later be overthrown and executed by the people of his country in December of that same year.

![]() Republic of China (Taiwan): President Lee Teng-hui issued a statement on 4 June strongly condemning the mainland Chinese response: "Early this morning, Chinese communist troops finally used military force to attack the students and others demonstrating peacefully for democracy and freedom in Tiananmen Square in Peking, resulting in heavy casualties and loss of life. Although we anticipated this mad action of the Chinese communists beforehand, it still has moved us to incomparable grief, indignation and shock."[76] The authorities also lifted a ban on telephone communications to encourage private contacts and counter the news blackout on the mainland.[52]

Republic of China (Taiwan): President Lee Teng-hui issued a statement on 4 June strongly condemning the mainland Chinese response: "Early this morning, Chinese communist troops finally used military force to attack the students and others demonstrating peacefully for democracy and freedom in Tiananmen Square in Peking, resulting in heavy casualties and loss of life. Although we anticipated this mad action of the Chinese communists beforehand, it still has moved us to incomparable grief, indignation and shock."[76] The authorities also lifted a ban on telephone communications to encourage private contacts and counter the news blackout on the mainland.[52]

![]() Singapore: Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, speaking on behalf of the Cabinet, said they were shocked and saddened by the response of the Chinese government, adding that "we had expected the Chinese government to apply the doctrine of minimum force when an army is used to quell civil disorder."[57]

Singapore: Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, speaking on behalf of the Cabinet, said they were shocked and saddened by the response of the Chinese government, adding that "we had expected the Chinese government to apply the doctrine of minimum force when an army is used to quell civil disorder."[57]

![]() Soviet Union: General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev did not explicitly condemn the actions, but called for reform. There was an interest on building relations on a recent summit in Beijing, but the events fueled discussion on human rights and Soviet foreign policy. There was some private criticism of the Chinese response.[50] Newly formed opposition groups condemned the military action. 10 days after the incident the government expressed regret, calling for political dialogue. Public demonstrations occurred at the Chinese embassy in Moscow. A spokesman on 10 June said the Kremlin was "extremely dismayed" at the incident.[77][78]

Soviet Union: General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev did not explicitly condemn the actions, but called for reform. There was an interest on building relations on a recent summit in Beijing, but the events fueled discussion on human rights and Soviet foreign policy. There was some private criticism of the Chinese response.[50] Newly formed opposition groups condemned the military action. 10 days after the incident the government expressed regret, calling for political dialogue. Public demonstrations occurred at the Chinese embassy in Moscow. A spokesman on 10 June said the Kremlin was "extremely dismayed" at the incident.[77][78]

![]() South Korea: The Foreign Ministry expressed "grave concern" and hoped for no further deterioration of the situation. The statement also encouraged dialogue to resolve the issue peacefully.[79]

South Korea: The Foreign Ministry expressed "grave concern" and hoped for no further deterioration of the situation. The statement also encouraged dialogue to resolve the issue peacefully.[79]

![]() Sweden: The Swedish government froze diplomatic relations with China.[80]

Sweden: The Swedish government froze diplomatic relations with China.[80]

![]() Thailand: The Thai government had the warmest relations with Beijing out of all ASEAN members, and expressed confidence that the "fluid situation" in China had passed its "critical point", though it was concerned that it could delay a settlement in the Cambodian–Vietnamese War.[56]

Thailand: The Thai government had the warmest relations with Beijing out of all ASEAN members, and expressed confidence that the "fluid situation" in China had passed its "critical point", though it was concerned that it could delay a settlement in the Cambodian–Vietnamese War.[56]

![]() United Kingdom: The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, expressed "utter revulsion and outrage", and was "appalled by the indiscriminate shooting of unarmed people." She promised to relax immigration laws for Hong Kong residents.[81]

United Kingdom: The Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher, expressed "utter revulsion and outrage", and was "appalled by the indiscriminate shooting of unarmed people." She promised to relax immigration laws for Hong Kong residents.[81]

![]() United States: Officially the United States Congress and media responded indignantly to the unfolding situation. President George H. W. Bush suspended military sales and visits. Large scale protests took place around the country.[59] However, George Washington University revealed that, through high-level secret channels on 30 June 1989, the US government conveyed to the government of the People's Republic of China that the events around the Tiananmen Square protests were an "internal affair" which could be dealt with as the Chinese government wished.[82]

United States: Officially the United States Congress and media responded indignantly to the unfolding situation. President George H. W. Bush suspended military sales and visits. Large scale protests took place around the country.[59] However, George Washington University revealed that, through high-level secret channels on 30 June 1989, the US government conveyed to the government of the People's Republic of China that the events around the Tiananmen Square protests were an "internal affair" which could be dealt with as the Chinese government wished.[82]

![]() Vietnam: despite Vietnam and China's history of strained relations, the Vietnamese government quietly supported the Chinese government. Media reported on the protests but offered no commentary, and state radio added that the PLA could not have stopped the action after "hooligans and ruffians insulted or beat up soldiers" and destroyed military vehicles. The government expressed that it wanted better relations with China, but did not want to go to the "extremes of Eastern Europe or Tiananmen" – referring to its own stability.[83]

Vietnam: despite Vietnam and China's history of strained relations, the Vietnamese government quietly supported the Chinese government. Media reported on the protests but offered no commentary, and state radio added that the PLA could not have stopped the action after "hooligans and ruffians insulted or beat up soldiers" and destroyed military vehicles. The government expressed that it wanted better relations with China, but did not want to go to the "extremes of Eastern Europe or Tiananmen" – referring to its own stability.[83]

![]() Yugoslavia: The national news agency Tanjug in the non-aligned country said the protest became a "symbol of destroyed illusions and also a symbol of sacrificed ideals which have been cut off by machine gun volleys and squashed under the caterpillars of heavy vehicles."[65]

Yugoslavia: The national news agency Tanjug in the non-aligned country said the protest became a "symbol of destroyed illusions and also a symbol of sacrificed ideals which have been cut off by machine gun volleys and squashed under the caterpillars of heavy vehicles."[65]

Chinese authorities summarily tried and executed many of the workers they arrested in Beijing. In contrast, the students – many of whom came from relatively affluent backgrounds and were well-connected – received much lighter sentences. Wang Dan, the student leader who topped the most wanted list, spent seven years in prison. Many of the students and university staff implicated were permanently politically stigmatized, some never to be employed again. Some dissidents were able to escape to overseas under Operation Yellowbird, organised from Hong Kong.[84]

Smaller protest actions continued in other cities for a few days. Some university staff and students who had witnessed the killings in Beijing organised or spurred commemorative events upon their return to school. At Shanghai's prestigious Jiaotong University, for example, the party secretary organised a public commemoration event, with engineering students producing a large metal wreath. However, these commemorations were quickly put down, with those responsible being purged.

During and after the demonstration, the authorities attempted to arrest and prosecute the student leaders of the Chinese democracy movement, notably Wang Dan, Chai Ling, Zhao Changqing and Wuer Kaixi. Wang Dan was arrested, convicted and sent to prison, then allowed to emigrate to the United States on the grounds of medical parole. As a lesser figure in the demonstrations, Zhao was released after six months in prison. However, he was once again incarcerated for continuing to petition for political reform in China. Wuer Kaixi escaped to Taiwan. He is married and holds a job as a political commentator on Taiwanese national radio.[85] Chai Ling escaped to France, and then to the United States. In a public speech given at the University of Michigan in November, 2007,[86] Wang Dan commented on the current status of former student leaders: Chai Ling started a hi-tech company in the US, while Li Lu became an investment banker in Wall Street and started a company. Wang Dan said his plan was to find an academic job in the US after receiving his PhD from Harvard University, although he was eager to return to China if permitted.

The Party leadership expelled Zhao Ziyang from the Politburo Standing Committee of the Communist Party of China (PSC), because he opposed martial law, and Zhao remained under house arrest until his death. Hu Qili, the other member of the PSC who opposed the martial law but abstained from voting, was also removed from the committee. He was, however, able to retain his party membership, and after "changing his opinion", was reassigned as deputy minister of Machine-Building and Electronics Industry. Another reform-minded Chinese leader, Wan Li, was also put under house arrest immediately after he stepped out of an airplane at Beijing Capital International Airport upon returning from his shortened trip abroad, with the official excuse of "health reasons." When Wan Li was released from his house arrest after he finally "changed his opinion" he, like Qiao Shi, was transferred to a different position with equal rank but mostly ceremonial role. Several Chinese ambassadors abroad claimed political asylum.[87][88]

The event elevated Jiang Zemin – then Mayor of Shanghai – to become the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China. Jiang's decisive actions in Shanghai, in closing down reform-leaning publications and preventing deadly violence, won him support from party elders in Beijing. Members of the government prepared a white paper explaining the government's viewpoint on the protests. An anonymous source within the PRC government smuggled the document out of China, and Public Affairs published it in January 2001 as the Tiananmen Papers. The papers include a quote by Communist Party elder Wang Zhen which alludes to the government's response to the demonstrations.

State media mostly gave reports sympathetic to the students in the immediate aftermath. As a result, those responsible were all later removed. Two news anchors who reported this event on 4 June in the daily 1900 hours (7:00 pm) news report on China Central Television were fired because they showed their sad emotions. Wu Xiaoyong, the son of a Communist Party of China Central Committee member, and former PRC foreign minister and vice premier Wu Xueqian were removed from the English Program Department of Chinese Radio International. Editors and other staff at the People's Daily (the newspaper of the Communist Party of China), including its director Qian Liren and Editor-in-Chief Tan Wenrui, were also removed from their posts because of reports in the paper which were sympathetic towards the students. Several editors were arrested, with Wu Xuecan, who organised the publication of an unauthorised Extra edition, sentenced to four years' imprisonment.

Journalist Rob Gifford said that much of the political freedoms and debate that occurred post-Mao and pre-Tiananmen ended after Tiananmen. For instance, some of the authors of the film River Elegy (He Shang) were arrested, and some of the authors fled Mainland China. Gifford concluded that "China the concept, China the empire, China the construct of two thousand years of imperial thinking" has forbidden and may always forbid "independent thinking" as that would lead to the questioning of China's political system. Gifford added that people born after 1970 had "near-complete depoliticization" while older intellectuals no longer focus on political change and instead focus on economic reform.[89]

The Tiananmen Square protests damaged the reputation of the PRC in the West. Western media had been invited to cover the visit of Gorbachev in May and were thus in an excellent position to cover some of the military action live through networks such as the BBC and CNN. Protesters seized this opportunity, creating signs and banners designed for international television audiences. Coverage was further facilitated by the sharp conflicts within the Chinese government about how to handle the protests. Thus, broadcasting was not immediately stopped.

All international networks were eventually ordered to terminate broadcasts from the city during the military action, with the government shutting down the satellite transmissions. Broadcasters attempted to defy these orders by reporting via telephone. Footage was quickly smuggled out of the country, including the image of "the unknown rebel." The only network which was able to record some images during the night was Televisin Espaola of Spain (TVE).[90][91]

CBS correspondent Richard Roth and his cameraman were imprisoned during the military action. Roth was taken into custody while in the midst of filing a report from the Square via mobile phone. In a frantic voice, he could be heard repeatedly yelling what sounded like "Oh, no! Oh, no!" before the phone was disconnected. He was later released, suffering a slight injury to his face in a scuffle with Chinese authorities attempting to confiscate his phone. Roth later explained he had actually been saying, "Let go!"

Images of the protests would strongly shape Western views and policy toward the PRC throughout the 1990s and into the 21st century. There was considerable sympathy for the student protests among Chinese students in the West. Almost immediately, both the United States and the European Union announced an official arms embargo, and China's image as a reforming country and a valuable ally against the Soviet Union was replaced by that of a repressive authoritarian regime. The Tiananmen protests were frequently invoked to argue against trade liberalization with mainland China and by the United States' Blue Team as evidence that the PRC government was an aggressive threat to world peace and US interests.

Meanwhile, state media was ordered to focus on dead soldiers, screening images often on television.[92] Among overseas Chinese students, the Tiananmen Square protests triggered the formation of Internet news services such as the China News Digest and the NGO China Support Network. In the aftermath of Tiananmen, organizations such as the China Alliance for Democracy and the Independent Federation of Chinese Students and Scholars were formed, although these organizations would have limited political impact beyond the mid-1990s.

The Tiananmen Square massacre occurred concurrently with the 1989 French Open tennis tournament. which was eventually won by Chinese American Michael Chang. At age 17, Chang became the youngest man to win a Grand Slam after defeating world number one Ivan Lendl in a fourth-round match on 5 June 1989, frequently refers to the Tiananmen Square massacre as providing added impetus to win the tournament:

"A lot of people forget that Tiananmen Square was going on. The crackdown that happened was on the middle Sunday at the French Open, so if I was not practicing or playing a match, I was glued to the television, watching the events unfold...I often tell people I think it was God's purpose for me to be able to win the French Open the way it was won because I was able to put a smile on Chinese people's faces around the world at a time when there wasn't much to smile about."[93]

The Tiananmen square protests dampened the growing concept of political liberalization in communist countries that was popular in the late 1980s; as a result, many democratic reforms that were proposed during the 1980s were swept under the carpet. Although there has been an increase in personal freedom since then, discussions on structural changes to the PRC government and the role of the Communist Party of China remain largely taboo.

Despite early expectations in the West that PRC government would soon collapse and be replaced by the democratic governance, the Communist Party of China maintained its grip on power, and the student movement which started at Tiananmen was in complete disarray.

In Hong Kong, the Tiananmen square protests led to fears that the PRC would renege on its commitments under one country, two systems following the impending handover in 1997, leading the new governor Chris Patten to attempt to expand the franchise for the Legislative Council of Hong Kong which led to friction with the PRC. There have been large candlelight vigils attended by tens of thousands in Hong Kong every year since 1989 and these vigils have continued following the transfer of power to the PRC in 1997.

The protests also marked a shift in the political conventions which governed politics in the People's Republic. Prior to the protests, under the 1982 Constitution, the President was a largely symbolic role. By convention, power was distributed between the positions of President, Premier, and the General Secretary, all of whom were intended to be different people to prevent the excesses of Mao-style dictatorship. However, after Yang Shangkun used his reserve powers as head of state to mobilize the military, the Presidency again became a position imbued with real power. Subsequently, the President became the same person as the General Secretary of the CPC, and wielded paramount power.

In 1989, neither the Chinese military nor the Beijing police had adequate anti-riot gear, such as rubber bullets and tear gas commonly used in Western nations to break up riots.[94] After the Tiananmen Square protests, riot police in Chinese cities were equipped with non-lethal equipment for riot control.

There was a significant impact on the Chinese economy after the incident. Foreign loans to China were suspended by the World Bank, Asian Development Bank, and governments;[95] tourism revenue decreased from US$2.2 billion to US$1.8 billion; foreign direct investment commitments were cancelled and there was a rise in defense spending from 8.6% in 1986, to 15.5% in 1990, reversing a previous 10 year decline.[96] The Chinese Premier Li Peng visited the United Nations Security Council on 31 January 1992, and argued that the economic and arms embargoes on China were a violation of national sovereignty.[97]

In the immediate aftermath of the protests, some within the Chinese government attempted to curtail free market reforms that had been undertaken as part of Chinese economic reform and reinstitute administrative economic controls. However, these efforts met with stiff resistance from provincial governors and broke down completely in the early 1990s as a result of the collapse of the Soviet Union and Deng Xiaoping's trip to the south. The continuance of economic reform led to economic growth in the 1990s,[citation needed] which allowed the government to regain much of the support that it had lost in 1989. In addition, none of the current PRC leadership played any active role in the decision to move against the demonstrators, and one major leadership figure Premier Wen Jiabao was Director of the Central Party Office and accompanied Zhao Ziyang to meet the demonstrators.

The protest leaders at Tiananmen were unable to produce a coherent movement or ideology that would last past the mid-1990s. Many of the student leaders came from relatively "well-off" sectors of society and were seen as out of touch with common people. A number of them were socialists[citation needed]. Many of the organizations which were started in the aftermath of Tiananmen soon fell apart due to personal infighting. Several overseas democracy activists were supportive of limiting trade with mainland China, which significantly decreased their popularity both within China and among the overseas Chinese community. A number of NGOs based in the US, which aim to bring democratic reform to China and relentlessly protest human rights violations that occur in China, remain. One of the oldest and most prominent of them, the China Support Network (CSN), was founded in 1989 by a group of concerned US and Chinese activists in response to Tiananmen Square.

Unlike the Cultural Revolution, about which people can still easily find information through government-approved books, magazines, websites, et cetera, this topic is forbidden by the government and accordingly generally cannot be found in mainland Chinese media or websites. Media are warned not to mention the event; web posts and other individual actions on-line are rigorously removed by censors or moderators.[citation needed]

The official media in mainland China views the military action as a necessary reaction to ensure stability. As the incident is not part of any education curriculum in China, usually Chinese youth born after the military action learn of the protests from hearsay, family and foreign media.[98] Every year there is a large rally in Victoria Park, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong, where people remember the victims and demand that the CPC's official view be changed; pan-democrat legislators initiate motions demanding vindication of the protesters which routinely fail due to the in-built pro-establishment blocking mechanism. In 2008, this vigil, attributed to be in support of the victims of the recent earthquake in south-east China, was reported for the first time in the mainstream Chinese press without mention of Tiananmen Square being made.[99]

Petition letters over the incident have emerged from time to time, notably from Dr. Jiang Yanyong and Tiananmen Mothers, an organization founded by a mother of one of the victims killed in 1989 where the families seek vindication, compensation for their lost sons, and the right to receive donations, particularly from abroad.[100] Dissidents are routinely rounded up, and Tiananmen Square is tightly patrolled on the anniversary of 4 June to prevent any commemoration on the Square.[citation needed]

After the PRC Central Government reshuffle in 2004, several cabinet members mentioned Tiananmen.[citation needed] In October 2004, during an official visit to France, President Hu Jintao reiterated that "the government took determined action to calm the political storm of 1989, and enabled China to enjoy a stable development." He insisted that the government's view on the incident would not change.[101]

In March 2004, Premier Wen Jiabao said in a press conference that during the 1990s there had been a severe political storm in the PRC. He stated that the Communist Central Committee successfully stabilized the open-door policy and protected the "Career of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics" amid the breakdown of the Soviet Union and radical changes in Eastern Europe[102]

For the 20th anniversary of the event in 2009, there was a growing will by Chinese people to talk openly about the event, and to start an inquiry.[103] The Chinese government blocked the use of social networking sites such as Twitter and Flickr, and the e-mail provider Hotmail in the days leading up to the anniversary.[104] It was also reported that Chinese airport vendors selling The Economist containing an article with discourse on the 4 June anniversary had the pages with the censored article systematically removed.[citation needed] Zhang Shijun, an ex-soldier who was 18 in 1989, was arrested after publishing an open letter to Hu Jintao, to encourage open talk on the issue.[103] Hong Kong and Macau Special Administrative Region governments have refused entry by students involved in the protests to return to mainland China.[105][106] On 5 June 2009, several Chinese staff at the television station in Guangzhou were suspended after they allowed around 10 seconds of the Tank Man footage and candlelight protests in Hong Kong to be broadcast on the mainland.[107]

Following the protests, officials banned controversial films and books, and shut down a large number of newspapers. Within one year, 12 percent of all newspapers, 8 percent of publishing companies, 13 percent of social science periodicals and more than 150 films were banned or shut down. In addition to this, the government also announced it had seized 32 million contraband books and 2.4 million video and audio cassettes.[115]

Currently, due to strong Chinese government censorship including Internet censorship, the news media are forbidden to report anything related to the protests. Websites related to the protest are blocked on the mainland.[116] A search for Tiananmen Square protest information on the Internet in Mainland China largely returns no results, apart from the government-mandated version of the events and the official view, which are mostly found on Websites of People's Daily and other heavily-controlled media.[117]

In January 2006, Google agreed to censor their mainland China site, Google.cn, to remove information about the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre,[118] topics such as Tibetan independence, Falun Gong and the political status of Taiwan. When people search for those censored topics, it will list the following at the bottom of the page in Chinese, "According to local laws and regulations and policies, some search results are not displayed." The uncensored Wikipedia articles on the 1989 protests, both in English and Chinese Wikipedia, have been attributed as a cause of the blocking of Wikipedia by the government in mainland China. The ban of Wikipedia in mainland China was lifted, but the link to this incident in Chinese Wikipedia remained dead.

In 2006, the American PBS program "Frontline" broadcast a segment filmed at Peking University, many of whose students participated in the 1989 protests. Four present-day students were shown a picture of the Tank Man, but none of them could identify what was happening in the photo. Some responded that it was a military parade, or an artwork.

On 15 May 2007, Ma Lik, the leader of the main loyalist political party in Hong Kong, provoked much criticism when he said that "there was not a massacre" during the protests, as there was "no intentional and indiscriminate shooting." He said Hong Kong was "not mature enough" for democracy for believing foreigners' rash claims that a massacre took place. He said that Hong Kong showed through its lack of patriotism and national identity that it would thus "not be ready for democracy until 2022."[119] His remarks were met with wide condemnation from the public.[120] He later acknowledged he might have been "rash and frivolous" with his comments but insisted that it was not a massacre.[120]