Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Penal transportation

|

Contents |

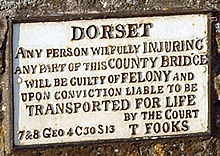

Transportation punished both major and petty crimes in Great Britain and Ireland from the 17th century until well into the 19th century. A sentence could be for life or a specific period. The penal system required the convicts to work, on government projects such as road construction, building works and mining, or assigned to free individuals as unpaid labour. Women were expected to work as domestic servants and farm labourers.

A convict who had served part of his time might apply for a ticket of leave permitting some prescribed freedoms. This enabled some convicts to resume a more normal life, to marry and raise a family, and a few to develop the colonies while removing them from the society. Exile was an essential component and thought a major deterrent. Transportation was also seen as a humane and productive alternative to execution, which would most likely have been the sentence to many if transportation had not been introduced.

In British colonial India, opponents of British rule were transported to the Cellular Jail in the Andaman islands.

North America was used for transportation from the early 17th century to the American Revolution of 1776. In the 17th century, it was done at the expense of the convicts or the shipowners. The first Transportation Act in 1718 allowed courts to sentence convicts to seven years' transportation to America. In 1720, extension authorized payments by the state to merchants contracted to take the convicts to America. Under the Transportation Act, returning from transportation was a capital offence.[2][3]

The gaols became overcrowded and dilapidated ships were pressed into service, the hulks moored in various ports as floating gaols. The number of convicts transported to North America is not verified although it has been estimated to be 50,000 by Dr John Dunmore Lang. These went originally to New England, the majority of prisoners taken in battle from Ireland and Scotland. Some were sold as slaves to the Southern states.[4]

From the 1620s until the American Revolution, the British colonies in North America received transported British criminals, effectively double the period that Australian colonies received convicts. The American Revolutionary War brought that to an end and, since the remaining British colonies in what is now Canada were close to the new United States of America, prisoners sent there might become hostile to British authorities. Thus, the British Government was forced to look elsewhere.

In 1787, the "First Fleet" departed from England, to found the first colony in Australia, as a penal colony. The arrival at Port Jackson, on 26 January 1788 (now Australia Day) is considered the founding event in the history of Sydney, as well as New South Wales and modern Australia in general. In 1803, Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) was also settled as a penal colony, followed by the Moreton Bay Settlement (Queensland) in 1824. The other Australian colonies were "free settlements", as non-convict colonies were known. However, Western Australia adopted transportation in 1851, to resolve a long-standing labour shortage. Until the massive influx of free immigrants during the Australian gold rushes of the 1850s, the settler population was dominated by convicts and their descendants.

Transportation from Britain/Ireland officially ended in 1868 although it had become uncommon several years earlier.[5]

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions