Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

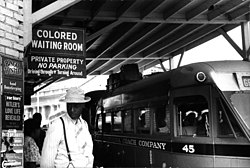

Jim Crow laws

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contents |

The phrase "Jim Crow Law" first appeared in 1904 according to the Dictionary of American English,[2] although there is some evidence of earlier usage.[3] The origin of the phrase "Jim Crow" has often been attributed to "Jump Jim Crow", a song-and-dance caricature of African Americans performed by white actor Thomas D. Rice in blackface, which first surfaced in 1832 and was used to satirize Andrew Jackson's populist policies. As a result of Rice's fame, "Jim Crow" had become a pejorative expression meaning "African American" by 1838, and from this the laws of racial segregation became known as Jim Crow laws.[3]

During the Reconstruction period of 1865–1877 federal law provided civil rights protection in the South for "freedmen" – the African Americans who had formerly been slaves. In the 1870s, white Democrats gradually returned to power in southern states, sometimes as a result of elections in which paramilitary groups intimidated opponents, attacking blacks or preventing them from voting. Gubernatorial elections were close and disputed in Louisiana for years, with extreme violence unleashed during the campaign. In 1877, a national compromise to gain southern support in the presidential election resulted in the last of the federal troops being withdrawn from the South. White Democrats had regained power in every Southern state.[4] The white, Democratic Party Redeemer government that followed the troop withdrawal legislated Jim Crow laws segregating black people from the state's white population.

Blacks were still elected to local offices in the 1880s, but the establishment Democrats were passing laws to make voter registration and elections more restrictive, with the result that participation by most blacks and many poor whites began to decrease. Starting with Mississippi in 1890, through 1910 the former Confederate states passed new constitutions or amendments that effectively disfranchised most blacks and tens of thousands of poor whites through a combination of poll taxes, literacy and comprehension tests, and residency and record-keeping requirements. Grandfather clauses temporarily permitted some illiterate whites to vote. Voter turnout dropped drastically through the South as a result of such measures.

Denied the ability to vote, blacks and poor whites could neither serve on juries nor in local office. They could not influence the state legislatures, and their interests were overlooked. While public schools had been established by Reconstruction legislatures, those for black children were consistently underfunded, even when considered within the strained finances of the South. The decreasing price of cotton kept the agricultural economy at a low.

In some cases, progressive measures to reduce election fraud acted against black and poor white voters who were illiterate. While the separation of African Americans from the general population was becoming legalized and formalized in the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s), it was also becoming customary. Even in cases in which Jim Crow laws did not expressly forbid black people to participate, for instance, in sports or recreation or church services, the laws shaped a segregated culture.[3]

In the Jim Crow context, the presidential election of 1912 was steeply slanted against the interests of Black Americans. Most blacks were still in the South, where they had been effectively disfranchised, so they could not vote at all. While poll taxes and literacy requirements banned many Americans from voting, these stipulations frequently had loopholes that exempted white Americans from meeting the requirements. In Oklahoma, for instance, anyone qualified to vote before 1866, or related to someone qualified to vote before 1866, was exempted from the literacy requirement; the only Americans who could vote before that year were white Americans, such that all white Americans were effectively excluded from the literacy testing, whereas all black Americans were effectively singled out by the law.[5]

Woodrow Wilson, a southern Democrat and the first southern-born president of the postwar period, appointed southerners to his cabinet. Some quickly began to press for segregated work places, although Washington, DC and federal offices had been integrated since after the Civil War. In 1913, for instance, the Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo–an appointee of the President–was heard to express his consternation at black and white women working together in one government office: "I feel sure that this must go against the grain of the white women. Is there any reason why the white women should not have only white women working across from them on the machines?"[6]

President Woodrow Wilson introduced segregation in Federal offices, despite much protest.[7] Wilson appointed Southern politicians who were segregationists, because of his firm belief that racial segregation was in the best interest of black and white Americans alike.[7] At Gettysburg on July 4, 1913, the semi-centennial of Abraham Lincoln's declaration that "all men are created equal", Wilson addressed the crowd:

How complete the union has become and how dear to all of us, how unquestioned, how benign and majestic, as state after state has been added to this, our great family of free men![8]

A Washington Bee editorial wondered if the "reunion" of 1913 was a reunion of those who fought for "the extinction of slavery" or a reunion of those who fought to "perpetuate slavery and who are now employing every artifice and argument known to deceit" to present emancipation as a failed venture.[8] One historian notes that the "Peace Jubilee" at which Wilson presided at Gettysburg in 1913 "was a Jim Crow reunion, and white supremacy might be said to have been the silent, invisible master of ceremonies."[8] (See also: Great Reunion of 1913)

The Civil Rights Act of 1875, introduced by Charles Sumner and Benjamin F. Butler, stipulated a guarantee that everyone, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, was entitled to the same treatment in public accommodations, such as inns, public transportation, theaters, and other places of recreation. This Act had little impact. An 1883 Supreme Court decision ruled that the act was unconstitutional in some respects, saying Congress was not afforded control over private persons or corporations. With white southern Democrats forming a solid bloc in Congress with power out of proportion to the percentage of population they represented, Congress did not pass another civil rights law until 1957.

In 1890, Louisiana passed a law requiring separate accommodations for colored and white passengers on railroads. Louisiana law distinguished between "white," "black" and "colored" (that is, people of mixed white and black ancestry). The law already specified that blacks could not ride with white people, but colored people could ride with whites before 1890. A group of concerned black, colored and white citizens in New Orleans formed an association dedicated to rescinding the law. The group persuaded Homer Plessy, who was only one-eighth "Negro" and of fair complexion, to test it.

In 1892, Plessy bought a first-class ticket from New Orleans on the East Louisiana Railway. Once he had boarded the train, he informed the train conductor of his racial lineage and took a seat in the whites-only car. He was directed to leave that car and sit instead in the "coloreds only" car. Plessy refused and was immediately arrested. The Citizens Committee of New Orleans fought the case all the way to the Supreme Court of the United States. They lost in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), in which the Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities were constitutional. The finding contributed to 58 more years of legalized discrimination against black and colored people in the United States.

In addition to the problems that Southerners encountered in learning free labor management after the end of slavery, Black Americans represented the Confederacy's Civil War defeat: "With white supremacy challenged throughout the South, many whites sought to protect their former status by threatening African Americans who exercised their new rights."[9] White Democrats used their power to segregate public spaces and facilities in law and reestablish dominance over blacks in the South.

One rationale for the systematic exclusion of Black Americans from southern public society was that it was for their own protection. An early 20th century scholar suggested that having allowed Blacks in White schools would mean "constantly subjecting them to adverse feeling and opinion", which might lead to "a morbid race consciousness".[10] This perspective took anti-Black sentiment for granted, because bigotry was widespread in the South.

After World War II, African Americans increasingly challenged segregation as they believed they had more than earned the right to be treated as full citizens because of their military service and sacrifices. The Civil Rights movement was energized by a number of flashpoints, including the attack on WWII veteran Isaac Woodard while he was in U.S. Army uniform. As the Civil Rights Movement gained momentum and used federal courts to attack Jim Crow statutes, the white-dominated governments of many of the southern states countered with passing alternative forms of restrictions.

The NAACP Legal Defense Committee (a group that became independent of the NAACP) – and its lawyer, Thurgood Marshall – brought the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) before the Supreme Court. In its pivotal 1954 decision, the Court unanimously overturned the 1896 Plessy decision. The Supreme Court found that legally mandated (de jure) public school segregation was unconstitutional. The decision had far-reaching social ramifications. De jure segregation was not brought to an end until the 1970s.[citation needed] History has shown that problems of educating poor children are not confined to minority status, and states and cities have continued to grapple with approaches.

The court ruling did not stop de facto or residentially based school segregation. Such segregation continues today in many regions. Some city school systems have also begun to focus on issues of economic and class segregation rather than racial segregation, as they have found that problems are more prevalent when the children of the poor of any ethnic group are concentrated.

Associate Justice Frank Murphy introduced the word "racism" into the lexicon of U.S. Supreme Court opinions in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944)[11]. He stated that by upholding the forced relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II, the Court was sinking into "the ugly abyss of racism." This was the first time that "racism" was used in Supreme Court opinion (Murphy used it twice in a concurring opinion in Steele v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co. 323 192 (1944) issued that day).[12] Murphy used the word in five separate opinions, but after he left the court, "racism" was not used again in an opinion for almost two decades. It next appeared in the landmark decision of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).

Interpretation of the Constitution and its application to minority rights continues to be controversial as Court membership changes. Some observers believe the Court has become more protective of the status quo.[13]

In the 20th century, the Supreme Court began to overturn Jim Crow laws on constitutional grounds. In Buchanan v. Warley 245 US 60 (1917), the court held that a Kentucky law could not require residential segregation. The Supreme Court in 1946, in Irene Morgan v. Virginia ruled segregation in interstate transportation to be unconstitutional, in an application of the commerce clause of the Constitution. It was not until 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka 347 US 483 that the court held that separate facilities were inherently unequal in the area of public schools, effectively overturning Plessy v. Ferguson, and outlawing Jim Crow in other areas of society as well. This landmark case consisted of complaints filed in the states of Delaware (Gebhart v. Belton); South Carolina (Briggs v. Elliott); Virginia (Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County); and Washington, D.C. (Spottswode Bolling v. C. Melvin Sharpe). These decisions, along with other cases such as McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Board of Regents 339 US 637 (1950), NAACP v. Alabama 357 US 449 (1958), and Boynton v. Virginia 364 US 454 (1960), slowly dismantled the state-sponsored segregation imposed by Jim Crow laws.

Along with Jim Crow laws, by which the state compelled segregation of the races, private parties such as businesses, political parties and unions created their own Jim Crow arrangements, barring blacks from buying homes in certain neighborhoods, from shopping or working in certain stores, from working at certain trades, etc. The Supreme Court outlawed some forms of private discrimination in Shelley v. Kraemer 334 US 1 (1948), in which it held that "restrictive covenants" that barred sale of homes to blacks or Jews or Asians were unconstitutional, because they represented state-sponsored discrimination, in that they were only effective if the courts enforced them.

The Supreme Court was unwilling, however, to attack other forms of private discrimination. It reasoned that private parties did not violate the Equal Protection clause of the Constitution when they discriminated, because they were not "state actors" covered by that clause.

In 1971, the Supreme Court, in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, upheld desegregation busing of students to achieve integration.

Rosa Parks' 1955 act of civil disobedience, in which she refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white man, was a catalyst in later years of the Civil Rights movement. Her action, and the demonstrations which it stimulated, led to a series of legislative and court decisions that contributed to undermining the Jim Crow system.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott led by Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., which followed Rosa Parks' action, was, however, not the first of its kind. Numerous boycotts and demonstrations against segregation had occurred throughout the 1930s and 1940s. These early demonstrations achieved positive results and helped spark political activism. K. Leroy Irvis of Pittsburgh's Urban League, for instance, led a demonstration against employment discrimination by Pittsburgh's department stores in 1947, launching his own influential political career.

In January 1964, President Lyndon Johnson met with civil rights leaders. On January 8, during his first State of the Union address, Johnson asked Congress to "let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined." On June 21, civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney, disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The three were volunteers aiding in the registration of African-American voters as part of the Mississippi Summer Project. Forty-four days later, the Federal Bureau of Investigation recovered their bodies, which had been buried in an earthen dam. The Neshoba County deputy sheriff, Cecil Price and 16 others, all Ku Klux Klan members, were indicted for the crimes; seven were convicted.

Building a coalition of northern Democrats and Republicans, President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[1] On July 2, President Johnson signed the historic legislation.[1][14] It invoked the commerce clause[1] to outlaw discrimination in public accommodations (privately owned restaurants, hotels, and stores, and in private schools and workplaces). This use of the commerce clause was upheld in Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States 379 US 241 (1964).[15]

By 1965 efforts to break the grip of state disfranchisement had been under way for some time, but had achieved only modest success overall and in some areas had proved almost entirely ineffectual. The murder of voting-rights activists in Philadelphia, Mississippi, gained national attention, along with numerous other acts of violence and terrorism against the president. Finally, the unprovoked attack on March 7, 1965, by state troopers on peaceful marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, en route to the state capitol in Montgomery, persuaded the President and Congress to overcome Southern legislators' resistance to effective voting rights legislation. President Johnson issued a call for a strong voting rights law and hearings began soon thereafter on the bill that would become the Voting Rights Act.[16]

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 ended legally sanctioned state barriers to voting for all federal, state and local elections. It also provided for Federal oversight and monitoring of counties with historically low voter turnout, as this was a sign of discriminatory barriers.

The Supreme Court of the United States held in the Civil Rights Cases 109 US 3 (1883) that the Fourteenth Amendment did not give the federal government the power to outlaw private discrimination, and then held in Plessy v. Ferguson 163 US 537 (1896) that Jim Crow laws were constitutional as long as they allowed for "separate but equal" facilities. In the years that followed, the court made this "separate but equal" requirement a hollow phrase by upholding discriminatory laws in the face of evidence of profound inequalities in practice.

Jim Crow laws were a product of the solidly Democratic South. Conservative white Southern Democrats, exploiting racial fear and attacking the corruption (real or perceived) of Reconstruction Republican governments, took over state governments in the South in the 1870s and dominated them for nearly 100 years, chiefly as a result of disenfranchisement of most blacks through statute and constitutions. In 1956, southern resistance to the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education resulted in a resolution called the Southern Manifesto. It was read into the Congressional Record and supported by 96 southern congressmen and senators, all but two of them southern Democrats.

The Jim Crow laws were a major factor in the Great Migration during the early part of the 20th century, because opportunities were so limited in the South that African Americans moved in great numbers to northern cities to seek a better life.

While African-American entertainers, musicians, and literary figures had broken into the white world of American art and culture after 1890, African-American athletes found obstacles confronting them at every turn. By 1900, white opposition to African-American boxers, baseball players, track athletes, and basketball players kept them segregated and limited in what they could do. But their prowess and abilities in all-African-American teams and sporting events could not be denied. Changing social attitudes and leadership by pioneers such as Jackie Robinson, who entered formerly all-white professional baseball in 1947, aided in lowering the barriers. African-American participation in all the major sports began to increase rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s.

Jim Crow laws were in many ways a model for the Nuremberg Laws, German legislation against Jews, which the Congress of the Nazi Party met to pass in 1935.[17]

Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan houses the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, an extensive collection of everyday items that promoted racial segregation or presented racial stereotypes of African Americans, for the purpose of academic research and education about their cultural influence.[18]

Examples of Jim Crow laws are shown at the National Park Service website. The examples include anti-miscegenation laws. Although sometimes counted among "Jim Crow laws" of the South, such laws were also passed by other states. Anti-miscegenation laws were not repealed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964[1] but were declared unconstitutional by the 1967 Supreme Court ruling in Loving v. Virginia.

| African American topics | |

|---|---|

|

Political movements

|

|

|

Sports

|

|

|

Ethnic sub-divisions

|

|

|

Diaspora

|

|

| Category– Portal | |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives – Left History – Libraries & Archives – Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions