|

|

History of union busting in the United States

The history of union busting in the United States dates back to the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century which produced a rapid expansion in factories and manufacturing capabilities. As workers moved away from farm work to factories, mines and other hard labor, they faced harsh working conditions such as long hours, low pay and health risks. Children and women worked in factories and generally received lower pay than men. The government did little to limit these injustices. Labor movements in the industrialized world developed that lobbied for better rights and safer conditions. Shaped by wars, depressions, government policies, judicial rulings, and global competition, the early years of the battleground between unions and management were adversarial and often identified with aggressive hostility. Contemporary opposition to trade unions known as union busting started in the 1940s and continues to present challenges to the labor movement. Union busting is a term used by labor organizations and trade unions to describe the activities that may be undertaken by employers, their proxies, workers and in certain instances states and governments usually triggered by events such as picketing, card check, organizing, and strike actions.[1] Labor legislation has changed the nature of union busting, as well as the organizing tactics that labor organizations commonly use.

[edit] Strike breaking and union busting, 1890s-1935

Hiring agencies specializing in anti-union practices has been an option available to employers from the bloody strikes of the last quarter of the nineteenth century, until today.[2]

Creative methods of union busting have been around for a long time. In 1907, Morris Friedman reported that a Pinkerton agent who had infiltrated the Western Federation of Miners managed to gain control of a strike relief fund, and attempted to exhaust that union's treasury by awarding lavish benefits to strikers.[3] However, many attacks against unions have used brute force of one sort or another.

[edit] Brute force attacks against unions

Unions such as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) were devastated by the Palmer Raids, carried out as part of the First Red Scare. The Everett Massacre (also known as Bloody Sunday) was an armed confrontation between local authorities and Industrial Workers of the World members which took place in Everett, Washington on Sunday, November 5, 1916. Later, communist-led unions were isolated or destroyed, and their activists purged with the assistance of other union organizations, during the Second Red Scare.

[edit] Union busting with military force

For approximately 150 years, union organizing efforts and strikes have been periodically opposed by police, security forces, National Guard units, special police forces such as the Coal and Iron Police, and/or use of the United States Army. Significant incidents have included the Haymarket Riot and the Ludlow massacre. The Homestead struggle of 1892, the Pullman walkout of 1894, and the Colorado Labor Wars of 1903 are examples of unions destroyed or significantly damaged by the deployment of military force. In all three examples, a strike became the triggering event.

- Pinkertons and militia at Homestead, 1892 - One of the first union busting agencies was the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which came to public attention as the result of a shooting war between strikers and three hundred Pinkerton agents during the Homestead Strike of 1892. When the Pinkerton agents were withdrawn, militia forces were deployed. The decisive defeat of a powerful strike resulted in the destruction of the local union.

- Federal troops crush the American Railway Union, 1894 - During the Pullman Strike, the American Railway Union (ARU) committed one of the first great acts of union solidarity by calling out its members according to the principle of industrial unionism. The action was very successful until twenty thousand federal troops were called out to crush the strike, and the national ARU was destroyed.

[edit] College students as strikebreakers in the Interborough Rapid Transit strike of 1905

Following a walk out of subway workers, management of Interborough Rapid Transit in New York City appealed to university students to volunteer as motormen, conductors, ticket sellers and ticket choppers. Stephen Norword discusses the phenomenon of students as strikebreakers in early 20th Century North America: "Throughout the period between 1901 and 1923, college students represented a major, and often critically important source of strikebreakers in a wide range of industries and services. (–) Collegians deliberately volunteered their services as strikebreakers and were the group least likely to be swayed by the pleas of strikers and their sympathizers that they were doing something wrong."[4]

[edit] Jack Whitehead, the first "King of Strike Breakers"

There were a significant number of strikes during the 1890s and very early 1900s. Strikebreaking by recruiting massive numbers of replacement workers became a significant activity.

Jack Whitehead saw opportunity in labor struggles; while other workers were attempting to organize unions, he walked away from his union to organize an army of strikebreakers. Whitehead was the first to be called "King of the Strike Breakers"; by deploying his private workforce during strikes of steelworkers in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Birmingham, Alabama, he became wealthy. By demonstrating how lucrative strikebreaking could be, Whitehead inspired a host of imitators.[5]

[edit] James Farley inherits the strikebreaker title

After Whitehead, men like James A. Farley and Pearl Bergoff turned union busting into a substantial industry. Farley began his strikebreaking career in 1895, and opened a detective agency in New York City in 1902. In addition to detective work, Farley accepted industrial assignments, specializing in breaking strikes of streetcar drivers.[6] Farley hired his men based in part upon courage and toughness, and in some strikes they openly carried firearms. They were paid more than the strikers had been. Farley was credited with a string of successful strikebreaking actions, employing hundreds, and sometimes thousands of strikebreakers. Farley was sometimes paid as much as three hundred thousand dollars for breaking a strike, and by 1914 he had taken in more than ten million dollars. Farley claimed that he had defeated thirty-five strikes in a row. But he suffered from tuberculosis, and as he faced death, he declared that he turned down the job of breaking a streetcar strike in Philadelphia because this time, "the strikers were in the right."[7]

[edit] Bergoff brothers make strikebreaking a family affair

Pearl Bergoff also began his strikebreaking career in New York City, working as a spotter on the Metropolitan Street Railway in Manhattan. His job was to watch conductors, making certain that they recorded all of the fares that they accepted. In 1905 Bergoff started the Vigilant Detective Agency of New York. Within two years his brothers joined the lucrative business, and the name was changed to the Bergoff Brothers Strike Service and Labor Adjusters. Bergoff's early strikebreaking actions were characterized by extreme violence. A 1907 strike of garbage cart drivers resulted in numerous confrontations between strikers and the strikebreakers, even when protected by police escorts. Strikers sometimes pelted the strikebreakers with rocks, bottles, and bricks launched from tenement rooftops.[8]

In 1909, the Pressed Steel Car Company at McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania fired forty men, and eight thousand employees representing sixteen nationalities walked out under the banner of the Industrial Workers of the World. Bergoff's agency hired strikebreaking toughs from the Bowery, and shipped vessels filled with unsuspecting immigrant workers directly into the strike zone. Other immigrant strikebreakers were delivered in boxcars, and were not fed during a two-day period. Later they worked, ate, and slept in a barn with two thousand other men. Their meals consisted of cabbage and bread.[9]

There were violent confrontations between strikers and strikebreakers, but also between strikebreakers and guards when the terrified workers demanded the right to leave. An Austro-Hungarian immigrant who managed to escape told his government that workers were being held against their will, resulting in an international incident. In addition to kidnapping, strikebreakers complained of deception, broken promises about wages, and tainted food.[10]

During federal hearings, Bergoff explained that "musclemen" under his employ would "get... any graft that goes on", suggesting that was to be expected "on every big job."[10] Other testimony indicated that Bergoff's "right-hand man", described as "huge in stature, weighing perhaps 240 pounds", surrounded himself with thirty-five guards who intimidated and fleeced the strikebreakers, locking them into a boxcar prison with no sanitation facilities when they defied orders.[11]

At the end of August a gun battle erupted, leaving six dead, six dying, and fifty wounded. Public sympathy began to swing away from the company, and toward the strikers. Early in September the company acknowledged defeat and negotiated with the strikers. Twenty-two had died in the strike. But Bergoff's business wasn't hurt by the defeat; he boasted of having as many as ten thousand strikebreakers on his payroll.[11] He was getting paid as much as two million dollars per strikebreaking job.[12]

[edit] Anti-union vigilantes during the First Red Scare

Unlike the American Federation of Labor, the Industrial Workers of the World opposed the First World War. The American Protective League (APL) was a pro-war organization formed by wealthy Chicago businessmen. At the height of its power the APL had 250,000 members in 600 cities. In 1918, documents from the APL showed that ten percent of its efforts (the largest of any category) were focused on disrupting the activities of the IWW. The APL burgled and vandalized IWW offices, and harassed IWW members. Such actions were illegal, yet were supported by the Wilson administration.[13]

[edit] Spies, "missionaries," and saboteurs

Strikebreaking by hiring massive numbers of tough opportunists began to lose favor in the 1920s; there were fewer strikes, resulting in fewer opportunities.[11][14] By the 1930s, agencies began to rely more upon the use of informants and labor spies.

Spy agencies hired to bust unions developed a level of sophistication that could devastate targets. "Missionaries" were undercover operatives trained to use whispering campaigns or unfounded rumors to create dissension on the picket lines and in union halls. The strikers themselves were not the only targets. For example, female missionaries might systematically visit the strikers' wives in the home, relating a sob story of how a strike had destroyed their own families. Missionary campaigns have been known to destroy not only strikes, but unions themselves.[15]

In the 1930s, the Pinkerton Agency employed twelve hundred labor spies, and nearly one-third of them held high level positions in the targeted unions. The International Association of Machinists was damaged when Sam Brady, a veteran Pinkerton operative, held a high enough position in that union that he was able to precipitate a premature strike. All but five officers in a United Auto Workers local in Lansing, Michigan were driven out by Pinkerton agents. The five who remained were Pinkertons. At the Underwood Elliott-Fisher Company plant, the union local was so badly injured by undercover operatives that membership dropped from more than twenty five hundred to fewer than seventy-five.[16]

[edit] Strikebreaking and union busting, 1936-1947

Employers in the United States have had the legal right to permanently replace economic strikers since the Supreme Court–s 1937 decision in NLRB v. Mackay Radio & Telegraph Co.[17]

Meanwhile, employers began to demand more subtle and sophisticated union busting tactics, and so the field called "preventive labor relations" was born.[18] The new practitioners were armed with degrees in industrial psychology, management, and labor law. They would use these skills not only to manipulate the provisions of national labor law, but also the emotions of workers seeking to unionize.[19]

[edit] Nathan Shefferman (Labor Relations Associates), 1940s-1950s

After passage of the Wagner Act, the first nationally known union busting agency was Labor Relations Associates of Chicago, Inc. (LRA). LRA was led by Nathan Shefferman, who produced a guide to union busting, and has been considered the –founding father– of the modern union avoidance industry.[17] Shefferman had been a member of the original NLRB, and became director of employee relations at Chicago-based Sears, Roebuck and Company. Sears had been engaged in blocking unions from the retail industry throughout the 1930s. The chain had "carried out a particularly vicious, ongoing war with the Teamsters union." Sears provided $10,000 seed money to launch LRA.[20]

By the late 1940s, LRA had nearly 400 clients. Shefferman's operatives set up anti-union employee groups called "Vote No" committees, developed ruses to identify pro-union workers, and helped arrange sweetheart contracts with unions that would not challenge management.[21] Consultants from LRA "committed numerous illegal actions, including bribery, coercion of employees and racketeering."[17]

Shefferman built "a daunting business on a foundation of false premises", of which "perhaps the most incredible–and most widely believed–is the myth that companies are at a disadvantage to unions organizationally, legally, and financially during a union-organizing drive." What businesses sought to accomplish through such propaganda was for Congress to amend the Wagner Act.[22]

[edit] Strikebreaking and union busting, 1948-1959

In 1956, Nathan Shefferman crushed a unionizing effort of the Retail Clerks Union at seven Boston-area stores by employing tactics that Walter Tudor, the Sears vice-president for personnel, described as "inexcusable, unnecessary and disgraceful." At a Marion, Ohio, Whirlpool plant, an LRA operative created a card file system which tracked employees' feelings about unions. Many of those he regarded as pro-union were fired. A similar practice took place at the Morton Frozen Foods plant in Webster City, Iowa. An employee recruited by LRA operatives wrote down a list of employees thought to favor a union. Management fired those workers. The list-making employee received a substantial pay increase. When the United Packinghouse Workers of America union was defeated, Shefferman arranged a sweetheart contract with a union that Morton Frozen Foods controlled, with no participation from the workers. From 1949 through 1956, LRA earned nearly $2.5 million dollars providing such anti-union services.[23]

In 1957, the United States Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in Labor and Management (also known as the McClellan Committee) investigated unions for corruption, and employers and agencies for union busting activities. Labor Relations Associates was found to have committed violations of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, including manipulating union elections through bribery and coercion, threatening to revoke workers' benefits if they organized, installing union officers who were sympathetic to management, rewarding employees who worked against the union, and spying on and harassing workers.[24] The McClellan Committee believed that "the National Labor Relations Board [was] impotent to deal with Shefferman's type of activity."[25]

[edit] Strikebreaking and union busting, 1960s-present

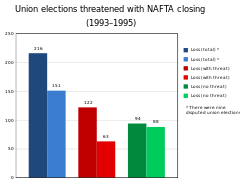

Studies done by Kate Bronfenbrenner at Cornell University showed how Union elections would be threatened with plant moving because of NAFTA. [26]

There is little evidence that employers availed themselves of anti-union services during the 1960s or the early 1970s.[27] However, under a new reading of the Landrum-Griffin Act, the Department of Labor took action against consulting agencies related to filing of required reports in only three cases after 1966, and between 1968 and 1974 it filed no actions at all. By the late 1970s, consulting agencies had stopped filing reports.

The 1970s and 1980s were an altogether more hostile political and economic climate for organized labor.[17] Meanwhile a new breed of union buster, with degrees in industrial psychology, management, and labor law, proved skilled at sidestepping requirements of both the National Labor Relations Act and Landrum-Griffin. In the 1970s the number of consultants, and the scope and sophistication of their activities, increased substantially. As the numbers of consultants increased, the numbers of unions suffering NLRB setbacks also increased. Labor's percentage of election wins slipped from 57 percent to 46 percent. The number of union decertification elections tripled, with a 73 percent loss rate for unions.[25]

Labor relations consulting firms began providing seminars on union avoidance strategies in the 1970s.[28] Agencies moved from subverting unions to screening out union sympathizers during hiring, indoctrinating workforces, and propagandizing against unions.[29]

By the mid-1980s, Congress had investigated, but failed to regulate, abuses by labor relations consulting firms. Meanwhile, while some anti-union employers continued to rely upon the tactics of persuasion and manipulation, other besieged firms launched blatantly aggressive anti-union campaigns. Although the general direction of professional union busting has been toward greater subtlety, strike-bound employers have turned once again to agencies that supply replacement workers, and professional security firms whose operatives "have proved to be little more than thugs."[citation needed] At the dawn of the 21st Century, methods of union busting have recalled similar tactics from the dawn of the 20th Century.[30]

[edit] History of labor legislation

[edit] Railway Labor Act, 1926

The Railway Labor Act[31][32] of 1926 was the first major piece of labor legislation passed by Congress. The RLA was amended in 1936 to expand from railroads and cover the emerging airline industry. At UPS, the mechanics, dispatchers, and pilots are the labor groups that are covered by the RLA. It was enacted because Railroad management wanted to keep the trains moving by putting an end to –wildcat– strikes. Railroad workers wanted to make sure they had an opportunity to organize, be recognized as the exclusive bargaining agent in dealing with a company, negotiate new agreements and enforce existing ones. Under the RLA, agreements do not have expiration dates; instead they have amendable dates which are indicated within the agreement.

[edit] Wagner Act, 1935

The National Labor Relations Act (NLRA)[33], often referred to as the Wagner Act, was passed by Congress July 5, 1935. It established the right to organize unions. The Wagner Act was the most important labor law in American history and earned the nickname "labor's bill of rights." It forbade employers from engaging in five types of labor practices: interfering with or restraining employees exercising their right to organize and bargain collectively; attempting to dominate or influence a labor union; refusing to bargain collectively and in "good faith" with unions representing their employees; and, finally, encouraging or discouraging union membership through any special conditions of employment or through discrimination against union or non-union members in hiring. Before the law, employers had liberty to spy upon, question, punish, blacklist, and fire union members. In the 1930s workers began to organize in large numbers. A great wave of work stoppages in 1933 and 1934 included citywide general strikes and factory occupations by workers. Hostile skirmishes erupted between workers bent on organizing unions, and the police and hired security squads backing the interests of factory owners who hated unionizing. Some historians maintain that Congress enacted the NLRA primarily to help stave off even more serious – potentially revolutionary – labor unrest. Arriving at a time when organized labor had nearly lost faith in Roosevelt, the Wagner Act required employers to acknowledge labor unions that were favored by a majority of their work forces. The Act established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), with oversight over union elections and unfair labor practices by employers.[34]

[edit] Taft-Hartley Act, 1947

The Taft-Hartley Act [35] was a major revision of the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (the Wagner Act) and represented the first major revision of a New Deal act passed by a post-war Congress. In the mid-term elections of 1946, the Republican Party won control of the upcoming Eightieth Congress, gaining majorities in both houses for the first time since 1931. On June 23, 1947, the Republican-controlled Congress passed, over President Truman's veto, the Labor-Management Relations Act of 1947 The Taft-Hartley Act widely interpreted as anti-labor. Labor leaders dubbed it a "slave labor" bill and twenty-eight Democratic members of Congress declared it a "new guarantee of industrial slavery."

| – |

Management always had the upper hand, of course; they had never lost it. But thanks to Taft-Hartley, the bosses could once again wage their war with near impunity. |

– |

-

- Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, Confessions of a Union Buster[36]

Taft-Hartley Act established unfair labor practices which can be charged against unions and employers. It allows specific "employer rights" which broadens an employer's arsenal during union organizing drives. It bans the closed shop, in which union membership is a precondition of employment at an organized workplace. It encouraged state "right to work" laws which prohibit mandatory union dues. It perpetuated red baiting. It gave management new weapons, while restricting fundamental union activities. For a time, Taft-Hartley instituted anti-communist loyalty oaths for union officers.[36]

Presidents have invoked the Taft-Hartley Act thirty-five times in attempts to halt work stoppages in labor disputes. All but two of those attempts were successful.

[edit] Landrum-Griffin Act, 1959

The Landrum Griffin Act of 1959 is also known as the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA)[37] defined financial reporting requirements for both unions and management organizations. Pursuant to LMRDA Section 203(b) employers are required to disclose the costs of any persuader activity as it regards consultants and potential bargaining unit employees.[38]

Martin Levitt's interpretation is as follows:

The law regulates labor unions' internal affairs and union officials' relationships with employers. But the law also required companies to report certain expenditures related to their anti-union activities. Fortunately for union busters, loopholes in the requirements allow management and their agents to ignore the provisions aimed at reforming their behavior.[39] The loopholes require consultants to file if they communicate with employees either for the purpose of persuading them not to join a union, or to gain knowledge about the employees or the union that may be passed on to the employer. However, most consultants accomplish these goals by indirect means, using supervisors and management as their first line of contact with employees. Even before the Act was passed, labor consultants had identified front-line supervisors as the most effective lobbyists for management.[40]

Landrum-Griffin also seeks to prevent consultants from spying on employees or the union. Information isn't to be compiled unless it is for the purpose of a specific legal proceeding. According to Martin Levitt, "It is easy for consultants to use this provision as a cover for "all kinds of information gathering."[40]

According to Martin Levitt, "because of Landrum-Griffin's vague language, attorneys are able to directly interfere in the union-organizing process without any reporting requirements. Therefore, "young lawyers run bold anti-union wars and dance all over Landrum-Griffin." The provisions of Landrum-Griffin allowing special rights for lawyers resulted in labor consultants working under the shield of labor attorneys, allowing them to easily evade the intent of the law."[41]

Martiin Levitt stated:

| – |

With the help of our trusted attorneys, our anti-union activities were carried out [under Landrum-Griffin] in backstage secrecy; meanwhile we gleefully showcased every detail of union finances that could be twisted into implications of impropriety or incompetence. |

– |

-

- Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, Confessions of a Union Buster[40]

[edit] The Hoxie List

During the period from roughly 1910 to 1914, Robert Hoxie compiled a list of methods used by employers' associations to attack unions. The list was published in 1921, as part of the book Trade Unionism in the United States:

- 1. Effective counter organization; employers parallel the union structure, trade against trade (local, district, and national), city against city, state against state, national against national, and federation against federation.[42]

- 2. Uncompromising war on the closed shop by asserting the right to hire and fire, to pay what the individual can be made to work for, and therefore to destroy uniformity and control hours, speed, and the conditions of employment generally; by continuous propaganda, conventions, meetings, literature and personal solicitations, showing the tyranny of the unions under closed shop rule, and the loss and waste in the closed shop from inefficient workers forced by the union upon employers, from loafing on the job, restrictions on output, and on apprenticeship; showing that the union label is a detriment rather than an advantage to the employer using it; urging employers not to use goods bearing the union label, nor to patronize any concern which does; and opposing the union label on publications of any branch of government.[42]

- 3. The expulsion of members who sign closed shop agreements, with forfeit of contributions to the reserve fund.[42]

- 4. Giving financial aid to employers in trouble because of attempts to withstand closed shop demands or to establish the open shop, by inducing banks to refund interest on loans during strikes, and getting owners not to enforce penalties on failure to live up to building contracts. The National Metal Trades Association, for instance, advocates a plan for the cooperation of bankers' associations to extend aid on a wide scale.[42]

- 5. Mutual aid in time of trial and trouble with unionism; taking orders of a struck shop and returning profit; furnishing men from shops of other members and of outsiders; paying members out of the reserve fund for holding out against unions–a kind of strike benefit; and endeavoring to secure special patronage for employers in trouble from members and outsiders.[42]

- 6. Refusal of aid to any enterprise operating under the closed shop.[42]

- 7. Advertisements in some newspapers and the withdrawal of advertisements from others friendly to unionism.[42]

- 8. Detachment of union leaders by promotion or bribery, honorary positions and social advancement, thus constantly depriving unions of the directive force of their strongest men.[42]

- 9. Discrediting union leaders and unions by exploiting their mistakes in strikes, or mismanagement of funds; appealing to the public by the prosecution of leaders; exposing records of fearful examples as types, e.g., Parks, O'Shea, and Madden, and by inciting to violence.[42]

- 10. Weeding out agitators and plain union men by blacklists, card catalogs, lists of employees, and by identification systems, for example, the Metal Trades' card catalog, and the Seaman's employment book. Employment agencies for employers' associations require lists of all formal employees, examine their records and require certificates of membership.[42]

- 11. Detaching workers from the union and the union's control by requiring an individual contract with penalties, i.e., the loss of unsettled wages called deposit in case of strike; by welfare plans, insurance and pensions to the workers which depend upon long, continuous service and are forfeited in case of strike; selling stock cheap, giving the feeling to the workers that they have a stake in the game, and also by bonus and premium systems; and by "going the unions one better," i.e., paying above the union scale, giving special advantage to superior workers, requiring good working conditions by the members of the association, establishing accident prevention bureaus, safety inspection, and giving care to the housing of employees.[42]

- 12. Conducting trade schools and agitating for continuation schools and vocational training; conducting trade schools themselves or helping to support them; having cities conduct continuation schools as in Cincinnati and Hartford. The National Metal Trades' Association cooperates with the University of Cincinnati in engineering courses there; providing "instructors" to teach the unskilled as does the National Founders' Association; advocating trade schools supported at public expense generally, and separate vocational schools; attacking the present system of academic education; donating sums to certain societies for promoting industrial education, e.g., the National Metal Trades Association has donated money to the National Association for the Promotion of Industrial Education.[42]

- 13. Securing foreknowledge of union plans by the spy system, use of detective agencies, spies in the union, the shadowing of leaders, gaining their confidence or using the dictagraph.[42]

- 14. Systematic organizations and use of strike breakers and counter-sluggers.[42]

- 15. Organization of counter-unions.[42]

- 16. Use of the police and militia. The unions, not having been able to enact the rules of the game into law, cannot gain their ends by the assertion of their rights. With the law on the side of property, indorsing [sic] individual liberty, to gain their ends they resort to force.[42]

- 17. Systematic appeal to the courts, the use of the injunction, systematic prosecution for violence, the employment of large corps of legal talent, the bringing into play of law and order leagues, suits for damages in case of strikes, and systematic attacks on the constitutionality of labor laws.[42]

- 18. Opposition to labor legislation by organizing lobbies to appear before both state and national bodies; by a system of calling upon members of association to send in letters and telegrams in great numbers; by having employers who will be most affected but who have good labor conditions appear before legislative committees to oppose labor legislation; and by having advertisements in many newspapers denouncing labor bills and calling upon citizens to write to legislators not to support them.[42]

- 19. Political agitation and action such as urging employers to neglect party lines and to vote for safe and sane men only; supporting antilabor statesmen and opposing labor politicians and demagogues, by sending funds, men, and literature into the districts of candidates; exposing the weaknesses of the labor vote and the failure of labor to defeat men the association supports; preventing the adoption of anti-injunction planks or other class legislation, or allowing only meaningless ones in party platforms; denouncing the initiative, referendum, and recall, especially the recall of judges and judicial decisions; and defending the courts and the constitution.[42]

- 20. Appealing to the public by the use of the press, publishing bulletins, and condemning papers which are unfriendly; systematically attacking unions and exploiting their violence; preventing the publication of seditious articles like those in the Los Angeles papers; giving statements to the press during strikes, pointing out that the strike for recognition and for the closed shop and not for better wages and conditions; pointing out, in case the strike is merely a matter of wages, that the trade can stand no more but is now paying higher than elsewhere, also that should wages be advanced prices would be higher, and the consumer would have to pay more in the face of the increased cost of living, and exploiting the losses of the workers in strikes, thus showing the folly of strikes; sending out circulars to educators and clergy; sending publications to the workers; for example, the National Founders' Association and the National Metal Trades' Association send their review to molders and machinists free; attacking Socialism and socialists and lauding ministers, educators, judges, and economists who show the fallacies of unionism and set forth the eternal verities.[42]

Hoxie summarized the underlying theories, assumptions, and attitudes of employers' associations of the period. These include the supposition that employers' interests are always identical to society's interests, such that unions should be condemned when they interfere; that the employers' interests are always harmonious with the workers' interests, and unions therefore try to mislead workers; that workers should be grateful to employers, and are therefore ungrateful and immoral when they join unions; that the business is solely the employer's to manage; that unions are operated by non-employees, and they are therefore necessarily outsiders; that unions restrict the right of employees to work when, where, and how they wish; and that the law, the courts, and the police represent absolute and impartial rights and justice, and therefore unions are to be condemned when they violate the law or oppose the police.[43]

Given the proliferation of employers' associations created primarily for the purpose of opposing unions, Hoxie poses counter-questions. For example, if every employer has a right to manage his own business without interference from outside workers, then why hasn't a group of workers at a particular company the right to manage their own affairs without interference from outside employers?[44]

[edit] See also

[edit] References

- ^ http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5604656

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page xiv.

- ^ The Autobiography of Big Bill Haywood, William D. Haywood, 1929, pages 157-58.

- ^ Norwood, Stephen H. (2002). Strikebreaking and Intimidation: Mercenaries and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America. Chapel Hill, NC, USA: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 15–17. ISBN 978-0-8078-2705-5. OCLC 59489222.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 40.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 41.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 41-42, 45, 47-48, and 53-54.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 55-56.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 58-59.

- ^ a b From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 59-60.

- ^ a b c From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 61.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 67.

- ^ Information from American Protective League Retrieved March 28, 2007.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 68.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 88-89.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 88.

- ^ a b c d "The Union Avoidance Industry in the United States", British Journal of Industrial Relations, John Logan, Blackwell Publishing Ltd, December 2006, pages 651–675.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 33.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 97.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 33-34.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 98-99.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 35.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, pages 98-100.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, pages 37-38.

- ^ a b From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 102.

- ^ Kate Bronfenbrenner, 'We'll Close', The Multinational Monitor, March 1997, based on the study she directed, 'Final Report: The Effects of Plant Closing or Threat of Plant Closing on the Right of Workers to Organize'.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page xvii.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 105.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 108-114.

- ^ From Blackjacks To Briefcases – A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States, Robert Michael Smith, 2003, page 119.

- ^ [Railway Labor Act]http://railwaylaboract.com/

- ^ http://www.nmb.gov/documents/rla.html

- ^ [National Labor Relations Act of 1935]http://www.nlrb.gov/about_us/overview/national_labor_relations_act.aspx

- ^ [US History Online] http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1612.html

- ^ (Full Text of Taft Hartley Act of 1947) http://vi.uh.edu/pages/buzzmat/tafthartley.html

- ^ a b Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 36.

- ^ (Dept. of Labor text of Landrum Griffin Act) http://www.dol.gov/compliance/laws/comp-lmrda.htm

- ^ (Dept. of Labor Instructions for LM-20 Agreement and Activities Report)http://www.dol.gov/esa/olms/regs/compliance/GPEA_Forms/lm-20_Instructions.pdf

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 41.

- ^ a b c Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, page 42.

- ^ Confessions of a Union Buster, Martin Jay Levitt, 1993, pages 42-43. Note that a new Interpretation of the "Advice" Exemption in Section 203(c) of the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act was issued on January 8, 2001, partly as a result of Mr. Levitt's comments about these loopholes. The Bush administration delayed, and then rescinded, the new interpretation.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Robert Franklin Hoxie, Lucy Bennett Hoxie, Nathan Fine, Trade Unionism in the United States, D. Appleton and Co., 1921, pages 190-95.

- ^ Robert Franklin Hoxie, Lucy Bennett Hoxie, Nathan Fine, Trade Unionism in the United States, D. Appleton and Co., 1921, pages 195-96.

- ^ Robert Franklin Hoxie, Lucy Bennett Hoxie, Nathan Fine, Trade Unionism in the United States, D. Appleton and Co., 1921, page 198.

[edit] Further reading

- Levitt, Marty. 1993. Confessions of a Union Buster. New York: Random House.

- Smith, Robert Michael. 2003. From Blackjacks to Briefcases: A History of Commercialized Strikebreaking and Unionbusting in the United States. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press.

- Reik, Millie. 2005. "Labor Relations (Major Issues in American History). Greenwood Press, ISBN 0313318646

- Norwood, Stephen H. 2003. "Strikebreaking and Intimidation: Mercenaries and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America". ISBN 0-8078-2705-3

[edit] External links

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives –

Left History –

Libraries & Archives –

Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions

|

Connect with Connexions

Newsletter Facebook Twitter

|