Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Csar Ch¡vez

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Csar Ch¡vez | |

|---|---|

Csar Ch¡vez, 1974 |

|

| Born | March 31, 1927 Yuma, Arizona, US |

| Died | April 23, 1993 (aged 66) San Luis, Arizona |

| Occupation | Farm worker, labor leader, and civil rights activist. |

| Parents | Librado Ch¡vez (father) Juana Estrada Ch¡vez (mother) |

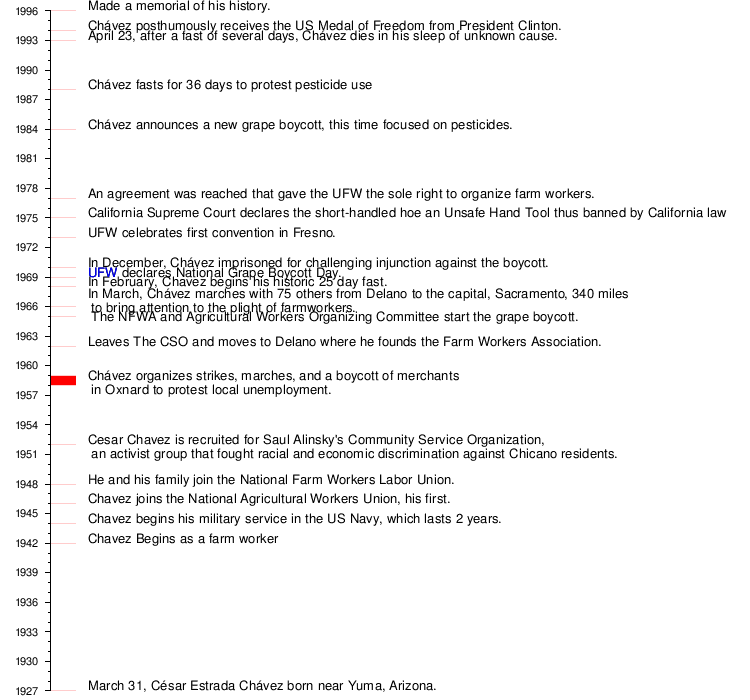

Csar Ch¡vez Estrada (Spanish pronunciation: [sesar tÊaîez]; March 31, 1927– April 23, 1993) was a Mexican American farm worker, labor leader, and civil rights activist who, with Dolores Huerta, co-founded the National Farm Workers Association, which later became the United Farm Workers (UFW).[1]

He became the best known Latino civil rights activist and as, founder of the United Farm Workers (UFW) was strongly promoted by the labor movement eager to enroll Hispanic members . His public-relations approach to unionism and aggressive but nonviolent tactics made the farm workers' struggle a moral cause with nationwide support. By the late 1970s, his tactics had forced growers to recognize the UFW as the bargaining agent for 50,000 field workers in California and Florida. However by the mid-1980s membership in the UFW had dwindled to around 15,000.

Chavez was charismatic; a self-taught rhetorical genius he created commitment by inspiring well educated Latino idealists with undiscovered organizing potential and encouraged them to offer a liberating, self-abnegating devotion to the farmworkers' movement. Claiming as his models Emiliano Zapata, Gandhi, Nehru and Martin Luther King, he called on his people to, "Make a solemn promise: to enjoy our rightful part of the riches of this land, to throw off the yoke of being considered as agricultural implements or slaves. We are free men and we demand justice."

After his death he became a major historical icon for the Latino community, and for liberals generally, symbolizing militant support for workers and for Hispanic power based on grass roots organizing and his slogan "S, se puede" (Spanish for "Yes, it is possible" or, roughly, "Yes, it can be done").

Supporters say his work led to numerous improvements for union laborers. His birthday has become Csar Ch¡vez Day, a state holiday in eight US states. Many parks, cultural centers, libraries, schools, and streets have been named in his honor in cities across the United States.

Contents |

Chavez was born on March 31, 1927, in the North Gila Valley near Yuma, Arizona. By 1938 the Great Depression had driven the Chavez family off its small farm and they became migrant farm workers in California. Chavez attended numerous schools but never finished the eighth grade.

Chavez worked in the fields until 1952, when he became an organizer for the Community Service Organization (CSO), a Latino civil rights group. He was hired and trained by Fred Ross as an organizer targeting police brutality. Ch¡vez urged Mexican Americans to register and vote, and he traveled throughout California and made speeches in support of workers' rights. He later became CSO's national director in 1958.[2]

In 1962 Ch¡vez left the CSO and co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) with Dolores Huerta. It was later called the United Farm Workers (UFW).

When Filipino American farm workers initiated the Delano grape strike on September 8, 1965, to protest for higher wages, Ch¡vez eagerly supported them. Six months later, Ch¡vez and the NFWA led a strike of California grape pickers on the historic farmworkers march from Delano to the California state capitol in Sacramento for similar goals. The UFW encouraged all Americans to boycott table grapes as a show of support. The strike lasted five years and attracted national attention. In March 1966, the US Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare's Subcommittee on Migratory Labor held hearings in California on the strike. During the hearings, subcommittee member Robert F. Kennedy expressed his support for the striking workers.[3]

These activities led to similar movements in Southern Texas in 1966, where the UFW supported fruit workers in Starr County, Texas, and led a march to Austin, in support of UFW farm workers' rights. In the Midwest, Csar Ch¡vez's movement inspired the founding of two Midwestern independent unions: Obreros Unidos in Wisconsin in 1966, and the Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) in Ohio in 1967. Former UFW organizers would also found the Texas Farm Workers Union in 1975.

In the early 1970s, the UFW organized strikes and boycotts to protest for, and later win, higher wages for those farm workers who were working for grape and lettuce growers. The union also won passage of the California Agricultural Labor Relations Act, which gave collective bargaining rights to farm workers. During the 1980s, Ch¡vez led a boycott to protest the use of toxic pesticides on grapes. Bumper stickers reading "NO GRAPES" and "UVAS NO"[4] (the translation in Spanish) were widespread. He again fasted to draw public attention. UFW organizers believed that a reduction in produce sales by 15% was sufficient to wipe out the profit margin of the boycotted product. These strikes and boycotts generally ended with the signing of bargaining agreements.[clarification needed]

The UFW during Ch¡vez's tenure was committed to restricting immigration. Csar Ch¡vez and Dolores Huerta fought the Bracero Program that existed from 1942 to 1964. Their opposition stemmed from their belief that the program undermined US workers and exploited the migrant workers. Since the Bracero program ensured a constant supply of cheap immigrant labor for growers, immigrants could not protest any infringement of their rights, lest they be fired and replaced. Their efforts contributed to Congress ending the Bracero Program in 1964. In 1973, the UFW was one of the first labor unions to oppose proposed employer sanctions that would have prohibited hiring undocumented immigrants. Later during the 1980s, while Ch¡vez was still working alongside UFW president, Dolores Huerta, the cofounder of the UFW, was key in getting the amnesty provisions into the 1986 federal immigration act.[5]

On a few occasions, concerns that undocumented migrant labor would undermine UFW strike campaigns led to a number of controversial events, which the UFW describes as anti-strikebreaking events, but which have also been interpreted as being anti-immigrant. In 1969, Ch¡vez and members of the UFW marched through the Imperial and Coachella Valleys to the border of Mexico to protest growers' use of undocumented immigrants as strikebreakers. Joining him on the march were both Reverend Ralph Abernathy and US Senator Walter Mondale.[6] In its early years, Ch¡vez and the UFW went so far as to report undocumented immigrants who served as strikebreaking replacement workers, as well as those who refused to unionize, to the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[7][8][9][10][11]

In 1973, the United Farm Workers set up a "wet line" along the United States-Mexico border to prevent Mexican immigrants from entering the United States illegally and potentially undermining the UFW's unionization efforts.[12] During one such event in which Ch¡vez was not involved, some UFW members, under the guidance of Ch¡vez's cousin Manuel, physically attacked the strikebreakers, after attempts to peacefully persuade them not to cross the border failed.[13][14][15]

Later in life, Ch¡vez focused on his education. The walls of his office in Keene, California (United Farm Worker headquarters) were lined with hundreds of books ranging in subject from philosophy, economics, cooperatives, and unions, to biographies of Gandhi and the Kennedys. He was a vegan.[16][17]

Csar Ch¡vez's birthday, March 31, is celebrated in California as a state holiday, intended to promote service to the community in honor of Ch¡vez's life and work. Many, but not all, state government offices, community colleges, and libraries are closed, only two public school districts in San Jose observe the day with no school. Texas also recognizes the day, and it is an optional holiday in Arizona and Colorado.

He is buried at the National Chavez Center, on the headquarters campus of the UFW, at 29700 Woodford-Tehachapi Road in the Keene community of unincorporated Kern County, California.[18] There is a portrait of him in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC.[19]

In 1973, college professors in Mount Angel, Oregon established the first four-year Mexican-American college in the United States. They chose Csar Ch¡vez as their symbolic figurehead, naming the college Colegio Cesar Chavez. In the book Colegio Cesar Chavez, 1973-1983: A Chicano Struggle for Educational Self-Determination author Carlos Maldonado writes that Ch¡vez visited the campus twice, joining in public demonstrations in support of the college. Though Colegio Cesar Chavez closed in 1983, it remains a recognized part of Oregon history. On its website the Oregon Historical Society writes, "Structured as a 'college-without-walls,' more than 100 students took classes in Chicano Studies, early childhood development, and adult education. Significant financial and administrative problems caused Colegio to close in 1983. Its history represents the success of a grassroots movement."[20] The Colegio has been described as having been a symbol of the Latino presence in Oregon.[21]

In 1992 Ch¡vez was awarded the Pacem in Terris Award. It was named after a 1963 encyclical letter by Pope John XXIII that calls upon all people of good will to secure peace among all nations. Pacem in Terris is Latin for "Peace on Earth."

Csar Ch¡vez died on April 23, 1993, of unspecified natural causes in a rental apartment in San Luis, Arizona. Shortly after his death, his widow, Helen Ch¡vez, donated his black nylon union jacket to the National Museum of American History, a branch of the Smithsonian.[22]

On September 8, 1994, Csar Ch¡vez was presented, posthumously, with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President William Clinton. The award was received by his widow, Helen Ch¡vez.

The California cities of Long Beach, Modesto, Sacramento, San Diego, Berkeley, and San Jose, California have renamed parks after him, as well as the City of Seattle, Washington. In Amarillo, Texas a bowling alley has been renamed in his memory. In Los Angeles, Csar E. Ch¡vez Avenue, originally two separate streets (Macy Street west of the Los Angeles River and Brooklyn Avenue east of the river), extends from Sunset Boulevard and runs through East Los Angeles and Monterey Park. In San Francisco, Csar Ch¡vez Street, originally named Army Street, is named in his memory. At San Francisco State University the student center is also named after him. The University of California, Berkeley, has a Csar E. Ch¡vez Student Center, which lies across Lower Sproul Plaza from the Martin Luther King, Jr., Student Union. California State University San Marcos's Chavez Plaza includes a statue to Ch¡vez. In 2007, The University of Texas at Austin unveiled its own Csar Ch¡vez Statue[23] on campus. Fresno named an adult school, where a majority percent of students' parents or themselves are, or have been, field workers, after Ch¡vez. In Austin, Texas, one of the central thoroughfares was changed to Csar Ch¡vez Boulevard. In Ogden, Utah, a four-block section of 30th Street was renamed Cesar Chavez Street. In Oakland, there is a library named after him and his birthday, March 31, is a district holiday in remembrance of him. On July 8, 2009, the city of Portland, Oregon, changed the name of 39th Avenue to Cesar Chavez Boulevard.[24] In 2003, the United States Postal Service honored him with a postage stamp. The largest flatland park in Phoenix Arizona is named after Chavez. The park features Cesar Chavez Branch Library and a life-sized statue of Chavez by artist Zarco Guerrero. In April, 2010, the city of Dallas, Texas changed street signage along the downtown street-grade portion of Central Expressway, renaming it for Ch¡vez[25]; part of the street passes adjacent to the downtown Dallas Farmers Market complex.

In 2004, the National Chavez Center was opened on the UFW national headquarters campus in Keene by the Cesar E. Chavez Foundation. It currently consists of a visitor center, memorial garden and his grave site. When it is fully completed, the 187-acre site will include a museum and conference center to explore and share Ch¡vez's work.[18]

In 2005, a Csar Ch¡vez commemorative meeting was held in San Antonio, honoring his work on behalf of immigrant farmworkers and other immigrants. Chavez High School in Houston is named in his honor, as is Cesar E. Chavez High School in Delano, California. In Davis, California; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Bakersfield, California and Madison, Wisconsin there are elementary schools named after him in his honor. In Davis, California, there is also an apartment complex named after Ch¡vez which caters specifically to low-income residents and people with physical and mental disabilities. In Racine, Wisconsin, there is a community center named The Cesar Chavez Community Center also in his honor. In Grand Rapids, Michigan, the business loop of I-196 Highway is named "Cesar E Chavez Blvd." The (AFSC) American Friends Service Committee nominated him three times for the Nobel Peace Prize.[26]

On December 6, 2006, California Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and First Lady Maria Shriver inducted Csar Ch¡vez into the California Hall of Fame located at The California Museum for History, Women, and the Arts.[27]

Csar Ch¡vez's eldest son, Fernando Ch¡vez, and grandson, Anthony Ch¡vez, each tour the country, speaking about his legacy.

Ch¡vez was referenced by Stevie Wonder in the song "Black Man," from the album Songs in the Key of Life, and by Tom Morello in the song "Union Song," from the album One Man Revolution.

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Cesar Chavez |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Csar Ch¡vez |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives – Left History – Libraries & Archives – Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions