Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

Information to change the world | |

Find Topics, Titles, Names related to your query |

|

|

Lenny Bruce

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2008) |

| Lenny Bruce | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Birth name | Leonard Alfred Schneider |

| Born | October 13, 1925 Mineola, New York, U.S. |

| Died | August 3, 1966 (aged 40) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Medium | Stand-up, film, television, books |

| Nationality | American |

| Years active | 1947–1966 |

| Genres | Satire, political satire, black comedy, improvisational comedy |

| Subject(s) | American culture, American politics, race relations, religion, human sexuality, obscenity, pop culture |

| Influences | Dick Gregory, Mort Sahl |

| Influenced | Richard Pryor,[1] George Carlin,[2] Bill Cosby,[3] David Cross, Jerry Seinfeld, Paul Krassner, Lewis Black,[4] Jon Stewart,[5] Peter Cook, Nick Di Paolo, Sam Kinison, Eddie Izzard, Bill Hicks, Rich Vos, Jerry Sadowitz, Cardell Willis, Denis Leary, Louis C.K., Andrew Dice Clay, Rick Shapiro, Tommy Chong |

| Spouse | Honey Harlow[6] |

| Notable works and roles | The Lenny Bruce Originals The Carnegie Hall Concert Let The Buyer Beware How to Talk Dirty and Influence People |

Leonard Alfred Schneider (October 13, 1925 – August 3, 1966), better known by the stage name Lenny Bruce, was an extremely influential and controversial American stand-up comedian, writer, social critic and satirist of the 1950s and 1960s, whose comedy revolved heavily around the social stigmas and taboos of the era in which he lived. His 1964 conviction in an obscenity trial was followed by a posthumous pardon, the first in New York state history.

Contents |

Bruce was born Leonard Alfred Schneider in Mineola, New York, grew up in nearby Bellmore and attended Wellington C. Mepham High School.[7] His youth was chaotic; his parents divorced when he was five years old and Lenny moved in with various relatives over the next decade. His mother, Sally Marr (ne Sadie Kitchenberg), was a stage performer who had an enormous influence on Bruce's career. After spending time working on a farm with a family that provided the stable surroundings he needed, Bruce joined the United States Navy at the age of 17 in 1942, and saw active duty in Europe until his dishonorable discharge in 1946, when he was charged with homosexuality.[8] (The Red Cross intervened, and the discharge was later changed to an honorable one.[9])

After a short stint in California spent living with his father, Bruce settled in New York City looking to make it as a comedian. However, he was in possession of little to differentiate himself from the thousands of other showbiz hopefuls that populated the city. One locale where these hopefuls congregated was Hanson–s, the diner where he first met the comedian Joe Ancis, who had a profound influence upon Bruce's approach to comedy. What Bruce did in his acts later on was a direct reflection of his meticulous schooling by Ancis.[10]

In 1947, soon after changing his last name to Bruce, he earned $12 and a free spaghetti dinner for his first stand-up performance in Brooklyn, New York. From that modest start, he got his first break as a guest (and introduced by his mother, who called herself "Sally Bruce") on the Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts show, doing a "Bavarian mimic" of American movie stars (e.g., Humphrey Bogart).

Bruce met his wife Honey Harlow, a stripper from Baltimore, Maryland, in 1951. They were married that same year, and Bruce was determined to get her off the stage.[11] This desire resulted in Bruce pursuing schemes designed to make as much money as possible, the most notable of which was the Brother Mathias Foundation scam, which resulted in Bruce being arrested in Miami, Florida later that year for impersonating a priest. He had been soliciting donations for a leper colony in British Guiana (now Guyana) under the auspices of the "Brother Mathias Foundation", which he had legally chartered - the name was his own invention, but possibly referred to the actual Brother Matthias who had befriended Babe Ruth at the orphanage to which Ruth had been confined as a child.[12] Bruce had stolen several priests' clergy shirts and a clerical collar while posing as a laundry man. He was found not guilty because of the legality of the New York state-chartered foundation, the actual existence of the Guiana leper colony, and the inability of the local clergy to expose him as an impostor. Later, in his semifictional autobiography How to Talk Dirty and Influence People, Bruce revealed that he had made about $8,000 in three weeks, sending $2,500 to the leper colony and keeping the rest.

In 1953, Bruce and Harlow eventually left New York for the West Coast, where they got work as a double act at the Cup and Saucer in Los Angeles, California. Bruce then went on to join the bill at the club Strip City. Harlow found employment at the Colony Club, which was widely known to be the best burlesque club in Los Angeles at the time.[13]

In late 1954, Bruce left Strip City and found work within the San Fernando Valley at a variety of strip clubs. As the master of ceremonies, his job was to introduce the strippers while performing his own ever-evolving material. The clubs of the Valley provided the perfect environment for Bruce to create new routines: according to Bruce's primary biographer, Albert Goldman, it was ––precisely at the moment when he sank to the bottom of the barrel and started working the places that were the lowest of the low–– that he suddenly broke free of ––all the restraints and inhibitions and disabilities that formerly had kept him just mediocre and began to blow with a spontaneous freedom and resourcefulness that resembled the style and inspiration of his new friends and admirers, the jazz musicians of the modernist school.– [14]

Bruce's early comedy career included writing the screenplays for Dance Hall Racket in 1953, which featured himself, his wife, Honey Harlow, and mother, Sally Marr, in roles; Dream Follies in 1954, a low-budget burlesque romp; and a children's film, The Rocket Man, in 1954. He also released four albums of original material on Berkeley-based Fantasy Records, with rants, comic routines, and satirical interviews on the themes that made him famous: jazz, moral philosophy, politics, patriotism, religion, law, race, abortion, drugs, the Ku Klux Klan, and Jewishness. These albums were later compiled and re-released as The Lenny Bruce Originals. Two later records were produced and sold by Bruce himself, including a 10-inch album of the 1961 San Francisco performances that started his legal troubles. Starting in the late 1950s, other unissued Bruce material was released by Alan Douglas, Frank Zappa and Phil Spector, as well as Fantasy. Bruce developed the complexity and tone of his material in Enrico Banducci's North Beach nightclub, "The hungry i," where Mort Sahl had earlier made a name for himself.

His growing fame led to appearances on the nationally televised Steve Allen Show, where he made his debut with an unscripted comment on the recent marriage of Elizabeth Taylor to Eddie Fisher, wondering, "will Elizabeth Taylor become bar mitzvahed?" He also began receiving mainstream press, both favorable and derogatory. Syndicated Broadway columnist Hy Gardner called Bruce a "fad" and "a one-time-around freak attraction," while Variety declared him "undisciplined and unfunny." Influential San Francisco columnist Herb Caen, however, was an early and enthusiastic supporter, writing in 1959:

They call Lenny Bruce a sick comic, and sick he is. Sick of all the pretentious phoniness of a generation that makes his vicious humor meaningful. He is a rebel, but not without a cause, for there are shirts that need un-stuffing, egos that need deflating. Sometimes you feel guilty laughing at some of Lenny's mordant jabs, but that disappears a second later when your inner voice tells you with pleased surprise, 'but that's true.'

On February 3, 1961, in the midst of a severe blizzard, he gave a famous performance at Carnegie Hall in New York. It was recorded and later released as a three-disc set, titled The Carnegie Hall Concert. In the liner notes, critic Albert Goldman described it as follows:

This was the moment that an obscure yet rapidly rising young comedian named Lenny Bruce chose to give one of the greatest performances of his career. ... The performance contained in this album is that of a child of the jazz age. Lenny worshipped the gods of Spontaneity, Candor and Free Association. He fancied himself an oral jazzman. His ideal was to walk out there like Charlie Parker, take that mike in his hand like a horn and blow, blow, blow everything that came into his head just as it came into his head with nothing censored, nothing translated, nothing mediated, until he was pure mind, pure head sending out brainwaves like radio waves into the heads of every man and woman seated in that vast hall. Sending, sending, sending, he would finally reach a point of clairvoyance where he was no longer a performer but rather a medium transmitting messages that just came to him from out there – from recall, fantasy, prophecy. A point at which, like the practitioners of automatic writing, his tongue would outrun his mind and he would be saying things he didn't plan to say, things that surprised, delighted him, cracked him up – as if he were a spectator at his own performance![15]

On October 4, 1961, Bruce was arrested for obscenity[16] at the Jazz Workshop in San Francisco; he had used the word "cocksucker" and riffed that "'to' is a preposition, 'come' is a verb", that the sexual context of "come" is so common that it bears no weight, and that if someone hearing it becomes upset, he "probably can't come." Although the jury acquitted him, other law enforcement agencies began monitoring his appearances, resulting in frequent arrests under charges of obscenity. The increased scrutiny also led to an arrest in Philadelphia, for drug possession the same year, and again in Los Angeles, California, two years later. The Los Angeles arrest took place in then-unincorporated West Hollywood, and the arresting officer was a young deputy named Sherman Block, who would later become County Sheriff.[17]

In April 1964, he appeared twice at the Cafe Au Go Go in Greenwich Village, with undercover police detectives in the audience. On both occasions, he was arrested after leaving the stage, the complaints again pertaining to his use of various obscenities.

A three-judge panel presided over his widely publicized six-month trial, with Bruce and club owner Howard Solomon both found guilty of obscenity on November 4, 1964. The conviction was announced despite positive testimony and petitions of support from Woody Allen, Bob Dylan, Jules Feiffer, Allen Ginsberg, Norman Mailer, William Styron, and James Baldwin – among other artists, writers and educators, and from Manhattan journalist and television personality Dorothy Kilgallen and sociologist Herbert Gans. [18] Bruce was sentenced, on December 21, 1964, to four months in the workhouse; he was set free on bail during the appeals process and died before the appeal was decided. Solomon later saw his conviction overturned; Bruce, who died before the decision, never had his conviction stricken.[19]

Despite his prominence as a comedian, Bruce appeared on network television only six times in his life. In his later club performances Bruce was known for relating the details of his encounters with the police directly in his comedy routine; his criticism encouraged the police to subject him to maximum scrutiny. These performances often included rants about his court battles over obscenity charges, tirades against fascism and complaints that he was being denied his right to freedom of speech.

He was banned outright from several U.S. cities, and in 1962 was banned from performing in Sydney, Australia. At his first show there Bruce took the stage, declared "What a fucking wonderful audience" and was promptly arrested.

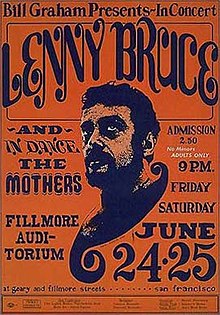

Increasing drug use also affected his health. By 1966 he had been blacklisted by nearly every nightclub in the United States, as owners feared prosecution for obscenity. Bruce did have a famous performance at the Berkeley Community Theatre in December 1965. It was recorded and became his last (live) album, titled "The Berkeley Concert"; his performance here has been described as lucid, clear and calm, and one of his best. His last performance took place on June 25, 1966, at The Fillmore Auditorium in San Francisco, on a bill with Frank Zappa and The Mothers of Invention. The performance was not remembered fondly by Bill Graham, who described Bruce as "whacked out on amphetamines"; Graham thought that Bruce finished his set emotionally disturbed. Zappa asked Bruce to sign his draft card, but the suspicious Bruce refused.

At the request of Hugh Hefner and with the aid of Paul Krassner, Bruce wrote an autobiography. Serialized in Playboy in 1964 and 1965, this material was later published as the book How to Talk Dirty and Influence People. Hefner had long assisted Bruce's career, featuring him in the television debut of Playboy's Penthouse in October 1959.

On August 3, 1966, Bruce was found dead in the bathroom of his Hollywood Hills home at 8825 N. Hollywood Blvd. The official photo, taken at the scene, showed Bruce lying naked on the floor, a syringe and burned bottle cap nearby, along with various other narcotics paraphernalia. Record producer Phil Spector, a friend of Bruce's, bought the negatives from the photographs to keep them from the press. The official cause of death was "acute morphine poisoning caused by an accidental overdose."[20]

He was interred in Eden Memorial Park Cemetery in Mission Hills, California, but an unconventional memorial on August 21 was controversial enough to keep his name in the spotlight. The service saw over 500 people pay their respects, led by Spector. Cemetery officials had tried to block the ceremony after advertisements for the event encouraged attendees to bring box lunches and noisemakers. Dick Schaap famously eulogized Bruce in Playboy, with the memorable last line: "One last four-letter word for Lenny: Dead. At forty. That's obscene."

Bruce is survived by his daughter, Kitty Bruce, who lives in Pennsylvania.[21]

At the time of his death his girlfriend was comedian Lotus Weinstock.[22]

On December 23, 2003,[23][24] 37 years after his death, Bruce was granted a posthumous pardon for his obscenity conviction by New York Governor George Pataki,[25] following a petition filed by Ronald Collins and David Skover with Robert Corn-Revere as counsel, the petition having been signed by several stars such as Robin Williams. It was the first posthumous pardon in the state's history. Pataki said his act was "a declaration of New York's commitment to upholding the First Amendment."

In 2004, Bruce was voted No. 3 of the 100 Greatest Stand-ups of All Time by Comedy Central behind Richard Pryor and George Carlin, both of whom cite Bruce as an influence (Carlin was arrested as an audience member for refusing to show identification at Bruce's December 1962 show at the Gate of Horn in Chicago, after the police ended the show and arrested Bruce for obscenity. They were placed together in the back of a paddywagon). In a similar survey conducted during 2007, Bruce was voted No. 30 of the 100 Greatest Comedy Stand-Ups by a public poll for the British Channel 4.[26]

Bruce was the subject of a 1974 biographical film directed by Bob Fosse and starring Dustin Hoffman called Lenny, based on the New York-based stage play of the same name, written by Julian Barry. A new documentary about Lenny, called "Looking for Lenny" is currently in production.[27]

The documentary "Lenny Bruce: Swear to Tell the Truth", directed by Robert B. Weide and narrated by Robert De Niro, was released in 1998.

|

|

This "In popular culture" section may contain minor or trivial references. Please reorganize this content to explain the subject's impact on popular culture rather than simply listing appearances, and remove trivial references. (April 2010) |

In part because of his freewheeling, jazz-like style, Lenny Bruce has always had fans in the music community.

By Bruce:

By others:

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | The Lenny Bruce Performance Film[2] | Himself | includes animated short film Thank You Mask Man by John Magnuson Associates |

| 1974 | Lenny | Biography starring Dustin Hoffman as Lenny Bruce | Hoffman was Nominated – Academy Award for Best Actor,

Nominated – BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role, Nominated – Golden Globe Award for Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Lenny Bruce |

Related topics in the Connexions Subject Index

Alternatives – Left History – Libraries & Archives – Social Change –

This article is based on one or more articles in Wikipedia, with modifications and additional content contributed by

Connexions editors. This article, and any information from Wikipedia, is covered by a

Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Unported License (CC-BY-SA) and the

GNU Free Documentation

License (GFDL).

We welcome your help in improving and expanding the content of Connexipedia articles, and in correcting errors. Connexipedia is not a wiki: please contact Connexions by email if you wish to contribute. We are also looking for contributors interested in writing articles on topics, persons, events and organizations related to social justice and the history of social change movements.

For more information contact Connexions